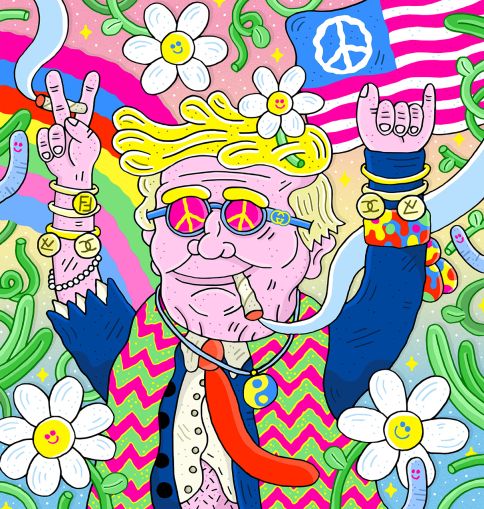

The Dead Heads of Commercial Real Estate (Including POTUS)

By Larry Getlen March 23, 2017 9:00 am

reprints

When you call the offices of Ripco Real Estate, the hold music you hear is not filled with the typical soft, inoffensive background sounds you might expect from a corporate phone system.

Instead, you hear the Grateful Dead. And not just any Dead, but the band recorded live in concert.

“Since our company’s inception in 1991, the only music you’ll find when you get put on hold is the Grateful Dead,” said Andrew Mandell, a 47-year-old managing partner at Ripco who saw the band over 50 times and said he can play every song the Grateful Dead ever performed—which numbers well over 400—on guitar.

“But it’s not just the Grateful Dead [on the hold music], but live Dead,” he noted. “That distinction is very important.”

Throughout the New York real estate world, love for the Grateful Dead—a band that established a die-hard following due to relentless touring, a seemingly endless repertoire and improvisational shows that turned familiar songs into unique creations—is ever-present, a mellow vacation and flipside to the hard-charging world of the real estate business.

So prevalent is this love, in fact, that one real estate executive even brought our current real estate mogul president to a show—and reports he had a heck of a time.

Billy Procida, the chief executive officer of Procida Funding and Advisors, gained notoriety in the 1980s as a 20-something Donald Trump acolyte, writing letter after letter to him until the mogul agreed to take him on as a real-life apprentice.

Procida, 54, is also a Deadhead, as the most dedicated of the band’s fans are known. He estimates he saw them over 200 times between attending his first Dead show in the eighth grade and the death of guitarist Jerry Garcia in 1995, which effectively ended the band. Since then, he has become friends with Dead guitarist Bob Weir, and in 2006, he brought these two seemingly disparate sides of his life together.

Weir was then in a band called RatDog, which mostly played songs from the Dead’s catalog. At a dinner with the band and others during a run of Beacon Theater shows in April of that year, Trump’s name came up, and Procida asked the band if they wanted The Apprentice star (his main claim to fame at the time) to introduce them at one of the shows. They voted yes, and Procida called his mentor.

This is how, on April 6, 2006, a crowd of Deadheads at the Beacon geared up for live music instead found Donald Trump taking the stage, telling them (as a joke) that Weir would not be able to perform that evening, but he, Trump himself, would take his place.

After the expected booing, Weir and the band came out and began the show. According to Procida, he asked Trump if he wanted to stay, saying he had a secure spot for them by the soundboard. But Trump not only wanted to watch the show: He spurned the safe space, deciding instead to wade into the crowd.

He stayed for the entire first set, and Procida reports he had a great time.

“He was right in it—we were right in the front,” Procida said. “We went out in the audience, and people were high-fiving him. He loved it.”

Procida is asked about Trump’s response to both the music and the hippie crowd, including any marijuana smoke presumably swirling around him.

“He liked it—he was enjoying himself,” Procida said of the music. “You don’t stay for an hour-and-a-half set of the Dead if you don’t like the Dead. He was diggin’ it.”

And the second part?

“I think he got a contact high,” admitted Procida. “He had a great time.”

Such is the affinity of the New York real estate world for the Grateful Dead. Even Donald Trump was pulled in.

But POTUS would likely marvel at the dedication of the most reverent. At the Midtown offices of Empire State Realty Trust at 111 West 33rd Street between Avenue of the Americas and Seventh Avenues, one of the private spaces is called “Beggar’s Tomb” after a lyric in the Dead’s “Uncle John’s Band.” (ESRT’s chairman and CEO, Anthony Malkin, is a serious Deadhead.) Robert Lapidus, the president and chief investment officer of L&L Holding Company, estimates he saw the band around 350 times before Garcia’s passing. If you include shows by offshoots—bands like RatDog that feature members of the Dead or musicians from their inner circle playing the catalog—that number swells to around 500.

“Once you saw them live, there was nothing like it,” said Lapidus, 56, who saw his first Grateful Dead show at Raceway Park in Englishtown, N.J., on Sept. 3, 1977, a show that is legendary in Dead circles for the over 100,000 fans that attended.

“People talk about religious experiences, going to pray or whatever,” Lapidus said. “To me, being at a Grateful Dead concert is as spiritual an event as ever existed.”

“The best part of the shows is the first twang, where you know exactly which song it is and where it’s going,” said Gary Trock, a senior vice president of retail leasing at CBRE. Trock estimates he saw the band around 200 times since his first show at Nassau Coliseum in 1972. Including offshoot shows since 1995, that total is around 450.

For Trock, much of the joy of these shows comes from delving into the musical details, comparing different versions of songs and relishing exciting renditions of favorites.

“It’s always been about how one [variation of a] song is better than the other,” Trock said. “You’re always comparing, like, ‘I heard a great “Candyman,” or a “Deal,” a “China Cat Sunflower” or a “Terrapin [Station].” ’ We all get crazy. ‘Oh, my god, I left early and missed “[We] Bid You Goodnight.” ’…We live for those special songs. That’s what motivates us to go back.”

When CO called Paul Pariser, the co-CEO of Taconic Investment Partners, the hold music was the Grateful Dead song “Estimated Prophet.” Pariser, 61, who Trock calls “an incredible lead guitarist”—yes, these guys all know one another and often hang out together at shows—estimates he saw the band over 50 times since his first Grateful Dead show at the Fox Theater in St. Louis in 1972 and is especially taken with the multilayered nature of the band’s improvisations.

“They’re so textured,” said Pariser, who plays in a Grateful Dead cover band called The Doo Dah Men, named after a line in the band’s classic song, “Truckin.”

“There’s a lot of stuff that goes on in the band’s songs. They’ve always had the ability to take one song through another and jam through it, and it’s so interesting. They were more creative than most.”

Todd Bassen, the managing principal and chief investment officer at Metropolitan Realty Associates, saw the band over 100 times after his first show on April 29, 1977, at New York’s Palladium (which is now New York University dorms).

Bassen, 57, has fond memories from his college days—he attended Emory University in Atlanta—of following the Dead from New Jersey to Miami with stops along the way, seeing as many shows as he could.

“Usually it was during finals, and I’d have to bring books and study,” he said. “It’s hard to study when you’re hitchhiking to see shows.”

Deadheads have always easily befriended other Deadheads, as being one makes you a member of a not-so-exclusive but still very special club. Bassen recalled how one Deadhead’s desire to connect got him in trouble.

“I was driving [with friends] in Tampa, Fla., and I had a Grateful Dead bumper sticker on my car. There was an AMC Pacer next to me,” he said. “The [driver] opened the window, and he was screaming at me as I was slowing down for a light. I rolled down my window. They had their windows down, and the guys in the car were all screaming, ‘Grateful Dead, Grateful Dead!’ They were all giving me a thumb’s up. But they were so busy trying to get my attention that the car slammed into a car stopped at the light, and there was a lot of damage to that car. I sat there for two minutes in disbelief that there was an accident because the guy saw my bumper sticker.”

Given how prolific and experimental the Dead are, invariably some of the real estate Deadheads saw the band at less than its best.

Mandell recalls just such a night at the Knickerbocker Arena in Albany when he sat in one of the first few rows, mere feet from Garcia.

“I’m so close that I’m making eye contact with Jerry, and [at one point] I think, The band’s just not on tonight. It was one of those nights where they just couldn’t get it together,” he said.

“I’m looking at Garcia, and…at a certain point put my hands in the air, as if to say, ‘What’s happening tonight?’ And he saw me, and he knew what I was walking about, and he kind of shrugged his shoulders as if to say, ‘That’s life with the Grateful Dead.’ And he was right. It wasn’t the best show I’ve ever seen, but it was up there with the best moments I’ve ever had at a Grateful Dead show.”

While the band’s appeal is vast and often surprising—people Procida has seen backstage at shows include Marriott Chairman Bill Marriott, Senator Al Franken and conservative commentator Ann Coulter—the large concentration of Deadheads in real estate might be partially explained by perceived similarities between the nature of the field and the life of the band.

Many real estate Deadheads told CO they picked their profession due in part to the independence it offered. This unchained mindset bonded many fans to the band.

“Twenty, 25 years ago, real estate wasn’t as institutional as it is today,” Mandell said. “One of the reasons young folks decided to pursue it was because it allowed for a certain amount of freedom, in that if you wanted to take a day off, you were free to do that. That coincides with the freedom the Grateful Dead played with, so I think that’s part of it.”

The Grateful Dead disbanded after Garcia’s death, but the surviving members, along with musicians heavily influenced by them, have created a blossoming scene of bands playing high-energy improvisational rock, often based on the Dead’s catalog.

These days, the most prominent of these include Dead & Company, which features Weir, Dead drummers Bill Kreutzmann and Mickey Hart and guitarist John Mayer; Phil Lesh & Friends, Dead bassist Phil Lesh’s outfit that finds him playing with revolving line-ups; and Joe Russo’s Almost Dead (JRAD), a supergroup of sorts that’s technically a cover band but features some of the best-played music in the scene led by Russo, who drummed in Further, a band featuring Weir and Lesh, from 2009 to 2014.

All the Deadheads we spoke to continue to see shows by these bands and others. Lapidus, who is friendly with Russo and Further/RatDog/Dead & Company keyboardist Jeff Chimenti, goes to 75 to 100 shows per year. This month, that included JRAD, who performed over the last two weekends at Brooklyn Bowl in Williamsburg, and Phil Lesh & Friends, who performed last week at the Capitol Theatre in Port Chester, N.Y. Lapidus also plans to catch at least 10 Dead & Company shows on their tour this summer.

In case the message is unclear, live music is life’s blood for Deadheads. Bassen tries to see one show a week, noting, “If I don’t see at least 50 shows a year, I’ve had a bad year.” Trock best summed up the mindset when, discussing Phish—an improvisational band often regarded as having inherited the Dead mantle due to a similar stance on touring, improvisation and fan relations—he said, “I’m not a Phish fan, but I’ve seen 40 Phish shows.”

Of those we spoke with, Procida has the deepest continuing involvement with the band. Set to marry his fiancée, Kelly, this summer, he’s having the wedding at the Dead & Company show at CitiField in June. Weir, a registered minister, will officiate.

Procida met Weir through a nervy set of circumstances. In the early 1990s, he said, he made a $10,000 bet with 10 friends, who put up $1,000 each, that he could wind up onstage with RatDog. Backstage at a show in Orlando, Fla., thanks to one of his lawyers—whose cousin was a band roadie—he told RatDog’s manager that he’d donate $10,000 to Weir’s favorite charity if he could get onstage and play with them for the encore.

The manager was reluctant, but when Weir walked by, he asked if Procida could play guitar.

“I did an air guitar of him with his head back, and he laughed and said O.K.,” Procida said.

On stage for the encore, Procida played with the band, believing that Mark Karan, their lead guitarist, was standing behind him. When the time came for the song’s guitar solo, Weir nodded toward Procida, who expected to see Karan behind him. But Karan wasn’t there. Weir was nodding at Procida.

“I go running over to Weir right in the middle of the song,” Procida said, “and I say, ‘I don’t play lead!’ And he goes, ‘Me either.’ Everybody’s laughing now, and Jeff Chimenti [takes a keyboard solo and] proceeds to blow the doors off the tune. He killed it.”

That marked the beginning of a friendship that has seen Procida play with Weir several times at Weir’s home, as well as other appearances on stage with RatDog, including in Rome for his 40th birthday.

“They took me to Italy, and I played in Villa Borghese Park in Rome,” Procida said. “I got to pick the song and played [the Bob Dylan tune, often played by the Dead] ‘When I Paint My Masterpiece’ in an ancient amphitheater. To play in a place full of rubble, standing there with Weir, was cool as shit.”

In time, the relationship turned professional as well. Procida and several other real estate executives, including Lapidus, helped bring a Grateful Dead exhibit to the New-York Historical Society in 2010. Procida has also been involved in several business ventures with the band and some in its circle, including helping bring the Dead-related board game Grateful Deadopoly to life, and working with Chimenti to market a medical device he co-invented—the Sleep Comfort Care Pad (now known as the Gecko nasal pad), which helps sleep apnea patients get a sounder night’s sleep—that, according to Procida, turned an $80,000 investment into $2.5 million in one year.

And this brings up, if not another full-on reason so many in real estate love the band, at least a healthy side benefit. When those in an industry so reliant on personal connections have a passion that coincidentally furthers those connections, it can only be good for business.

“I’ve made more real estate deals at Dead shows than I have on golf courses and all on handshakes,” Procida said.

“We have 150 investors in our fund, and half of them are Deadheads. You do business with a Deadhead, generally speaking, they’re like-minded and kind. In 36 years, I’ve never been screwed by a Deadhead.”