Is Sunnyside Yards a Beacon of Affordable Housing and New Development? Perhaps.

By Terence Cullen February 15, 2017 9:45 am

reprints

“Buy land, AJ, ‘cause God ain’t making any more of it.”

That paternal advice passed on from father to son during an episode of The Sopranos nearly 15 years ago has taken on a whole deeper meaning in New York City these days. So precious has land become—driving up both commercial and residential rents—that developers have been left to create land where there was none before.

For centuries, master builders both in the government and the private sector have aimed to do that at Sunnyside Yards in western Queens. The nearly 200-acre parcel of land has for more than a century been a literal hole in the ground that touches Long Island City, Astoria, Sunnyside and Woodside. While these neighborhoods have seen a rash of development in the last 20 years, the 117-year-old rail yard has sat where it was without experiencing the same kind of love.

That could be until now. A long-awaited feasibility study released by the city’s economic development wing last week indicated that it would in fact be possible to build a platform or, in industry speak, deck, over Sunnyside Yards. The conclusion of the study means that Mayor Bill de Blasio’s plan to build a whole new residential complex could move forward—setting up what’s sure to be a spirited debate between the various stakeholders in the process.

“It’s definitely complicated; there’s a lot to it,” said Robert Knakal, the chairman of New York investment sales at Cushman & Wakefield. “But given the location it is absolutely feasible to build there provided that the incentive package” is enticing for developers.

So what happens next? Well, the short answer is no one really knows. What’s certain is that shovels will not be hitting the ground once this recent batch of snow melts. In fact, moving forward on a plan for Sunnyside Yards still remains as complex—and as far out—as the hundreds of miles of track that lay there.

People familiar with the yards and the long-standing plans to build over them said there are still many steps to be taken. It will likely have to be done in multiple phases, possibly with various developers, and requires a unique financing model. Amtrak, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority and private landowners all own various plots of the land on which the tracks lay, meaning the entities would all have to agree on a plan. Plus, there are the surrounding communities, which will most likely have to weigh in on zoning approvals for the complex.

“Someone’s got to start the discussion on this, because it is probably one of the largest parcels in the city of undeveloped, prime land that could be the next great New York City project,” said Carlo Scissura, the president and chief executive officer of the New York Building Congress. “What’s the next grand project? It could be Sunnyside Yards.”

The 196-page study, which was commissioned by the New York City Economic Development Corporation, proved that Sunnyside Yards could be developed over structurally, geologically and financially. FXFowle Architects, Parsons Brinckerhoff and HR&A Advisors conducted the analysis, which was originally due out last summer, but fell behind schedule for undisclosed reasons as Crain’s New York Business reported in October 2016. Those who are familiar with the area say the fact that the study was actually completed is a victory for the mayor, who announced his Sunnyside Yards plan two years ago this month.

“The feasibility study is a very important step toward at some point realizing the potential of this enormous asset that people have been looking at for nearly a century,” said Christopher Jones, a vice president and the chief planner at urban think tank Regional Plan Association. “It laid out what is possible under different scenarios—taking a good look at what all of the challenges are for financing and constructing different types of development over the yards.”

Those plans follow three scenarios—one primarily residential, another with a commercial component and a destination-focused option—that are primarily focused on creating housing. Under these plans, the cost could be anywhere from $16 billion to $19 billion. Anywhere from 14,000 to 24,000 units could be created, the study concludes, of which about 4,200 to 7,200 would be designated as affordable. Under one scenario, roughly 3.5 million to 4.8 million square feet of Class A office space would be created. The destination master plan calls for up to 1.5 million square feet of mixed-use space alongside residential housing.

All of those below-market apartment projections fall short of what de Blasio originally intended when he announced the plan in February 2015 during his annual State of the City address. He likened the plan to Stuyvesant Town-Peter Cooper Village in Manhattan, Starrett City in Brooklyn and Co-op City in the Bronx—all of which were created in the mid-20th century to provide middle-class housing in New York. De Blasio in the address pledged to create 11,250 affordable units at Sunnyside Yards (if urban planners found it was buildable), which would mimic the original number of units at Stuy Town-Peter Cooper Village.

The report also pulls out a cheaper option separate from the three scenarios. At $10 billion it would be to build over just 70 percent on the yard—the portion owned by Amtrak. The report found that 11,000 to 15,000 residential units could be built there. Of those, about 3,300 to 4,500 apartments would be deemed affordable.

Likely, the platform could be raised above the current streetscape, according to the study. (Think of the original World Trade Center, which was raised up to 50 feet from West Street on one side of the complex.) Various building heights are floated in the report depending on the types of properties.

“It’s challenging, but it’s both physically and financially feasible,” Deputy Mayor Alicia Glen said in a statement released by the EDC, which did not comment further by press time. “We look forward to bringing these results back to the community, elected officials and other stakeholders as we explore this incredible opportunity to connect neighborhoods and build a stronger city.”

While many have explored plans for Sunnyside Yards, several industry veterans said this is the most comprehensive study anyone has ever conducted on developing over the yards.

“It’s good that after many, many years of having people talk about opportunities in Sunnyside that the city has taken the time to do a really detailed analysis of both the costs and the benefits of decking over the yards,” said Seth Pinsky, a vice president at RXR Realty and the president of the EDC from 2008 to 2013. “What came out of the analysis is that though the number of acres in a prime location is hard to ignore and though there seems to be a path where development could be possible, it would be a very difficult project to undertake and extremely costly.”

He added, “The question I think city officials and those who care about the city need to ask is, ‘Is this the right place to prioritize at this point?’ ”

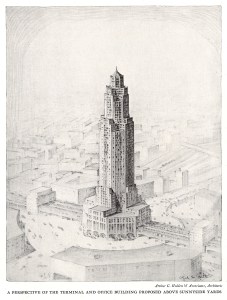

Overly ambitious master builders have had their eyes on decking over the yards practically since the Pennsylvania Railroad completed it in 1910. RPA released its first regional plan for improving the metro area in 1929, suggesting that a massive tower could be built atop Sunnyside Yards. That was a time of limited zoning when such things were easier to get erected, Jones noted. But, alas, the Great Depression forced that idea to be tabled.

“People would just draw something on a map and think that before too long some ambitious developer or city mogul would build it,” Jones said.

Sunnyside Yards has practically served as the El Dorado of development: a city of gold that many have sought but no one could find. Slopes rise and fall throughout the yard for trains that are headed to or from Manhattan. As the neighboring Long Island City has become increasingly developed over the last 15 years, the development community has noted that Sunnyside Yards presents a rare opportunity when it comes to size.

“Unless you’re going to close one of the airports and sell off the land, there’s nothing like that anymore,” Knakal said.

Gov. Nelson Rockefeller, known for a series of infrastructure and real estate projects in the 1960s through the 1970s, planned to platform the yards for development more than 50 years ago. Middle-class housing bigwig Samuel LeFrak also had ambitions for an affordable village above the rail yard. In the early 2000s, a decked-over Sunnyside Yards was the lynchpin to the city’s failed bid to host the 2012 Olympics (it would have been home to a stadium and the athletes’ village).

Former Mayor Daniel Doctoroff in an opinion piece for The New York Times again floated decking Sunnyside Yards in November 2014. Doctoroff, who led the botched Olympics bid, once again proposed a residential community as well as an exhibition hall that would replace the Jacob K. Javits Convention Center in Manhattan. Selling the land of the hypothetically defunct Far West Side Javits Center along with revenue from the new one would significantly finance the Sunnyside Yards project, suggested Doctoroff, who declined via a spokesman to comment for this story.

But the Javits Center is getting a $1 billion expansion, so it isn’t expected to go anywhere. Experts said a creative way to finance the project would have to be developed. The government would likely have to invest a significant amount of capital for the platform and other phases of the project, Pinsky said.

“What the report seemed to point out is that for any development to take place, whether it’s a public effort or a public-private effort, the public sector is going to have to come up with a lot of money to make it financially viable,” he said. “The city would have to put capital on the table, probably. They were big numbers.”

Constructing the platform itself is another matter. The jury is mixed on whether the model used elsewhere in the city could be exported to this. After all, Related Companies and Oxford Properties Group are developing a city within a city at Hudson Yards above a 26-acre rail yard on the Far West Side. Before that, a significant amount of rail bed in Brooklyn known as the Atlantic Yards agreed to be platformed to make way for parts of Forest City Ratner Companies’ Pacific Park development.

There are those who believe those two examples are proof that the same model can now be exported to Sunnyside Yards.

But Jones, an urban planner with RPA since 1994, said that building the platform, which could cover up to 85 percent of the yard, would have many moving parts. Mainly, he said it requires navigating an active train yard used by the MTA, Amtrak and NJ Transit.

“It is an enormous amount of acreage that would have to be decked over, which is no small feat from an engineering and financial standpoint. It’s not in the middle of a wasteland,” he said. “Sunnyside Yards is in the middle of one of the more active areas of Queens. Scale and complexity are really the bigger differences between Sunnyside and the other places” in the city where this has been done.

Matt Chaban, a former real estate reporter and the new policy director at the Center for an Urban Future think tank, suggested one viable option is for the government to build the platform and sell it off in plots. By creating smaller pieces, it makes bidding on Sunnyside Yards more competitive—driving up the potential revenue as well as creating variety at the complex.

“If you could figure out a financing structure to create the deck publicly, and then parcel off the land, you can create more parcels and diversify the development—then you get more for those parcels,” he said.

The report notes that, among other things, the city now has to engage the various stakeholders who would be impacted by the project. But some might not be willing to hop on board. The day after de Blasio announced the Sunnyside Yards plan, his frenemy Gov. Andrew Cuomo said the state-run MTA would not cooperate because it seemed impractical. (Cuomo’s spokeswoman didn’t respond to a request for comment.)

An Amtrak official in a statement released by the EDC last week indicated it was interested in working with the city moving forward. The rail corporation currently has plans for a high-speed train facility at Sunnyside Yards, and the feasibility report notes that the government would have to work with Amtrak on how the design might be impacted by a platform.

Residents of nearby Sunnyside Gardens have expressed concern over the project. Their councilman, Jimmy Van Bramer, has publically met the project with skepticism in the last two years. He did not return multiple requests for comment via a spokeswoman.

Borough President Melinda Katz, whose office would likely have influence on any zoning changes for the project, expressed interest in working on developing Sunnyside Yards. She, too, noted that the affordable housing component should be met, and the say of residents surrounding the potential mega-development aren’t negatively impacted by the hypothetical construction.

“Potential development at Sunnyside Yards has long been attractive, given the current growth and development throughout Long Island City and western Queens,” she said in a statement provided to CO. “While this feasibility study was a step in the right direction, it is highly preliminary and, as acknowledged in the study itself, only the first stage in a multi-step, multi-year process.”

Naturally, something like this is going to take a lot of give and take, Scissura said. This is a concept older even than the rail yards themselves.

“In New York, whenever you have a parcel, big or small, with competing interests and different entities that have ownership, really there are going to be challenges,” Scissura said. “But we’ve done it before, we’ve built great before. There’s no reason we shouldn’t be building great now.”

With additional reporting provided by Liam La Guerre.