15 Years After 9/11, Larry Silverstein Finally Recreated WTC

While Larry Silverstein was still in the process of acquiring the Twin Towers in early 2001, the then 69-year-old was walking along Madison Avenue when he was struck by a vehicle, breaking his pelvis.

He called his team into the hospital and asked his doctors to cut the painkillers.

“Because he was bidding on the World Trade Center, he had to be lucid,” remembered Mary Ann Tighe, the chief executive officer of the tri-state region of CBRE.

It would be difficult to think of a more troubling omen of what was to come. Only six weeks after Silverstein’s company, Silverstein Properties, took title to the 10-million-square-foot World Trade Center, Al Qaeda terrorists staged the worst assault in United States history on the towers, killing over 2,600 people. (See our video interview with Silverstein on 9/11 here.)

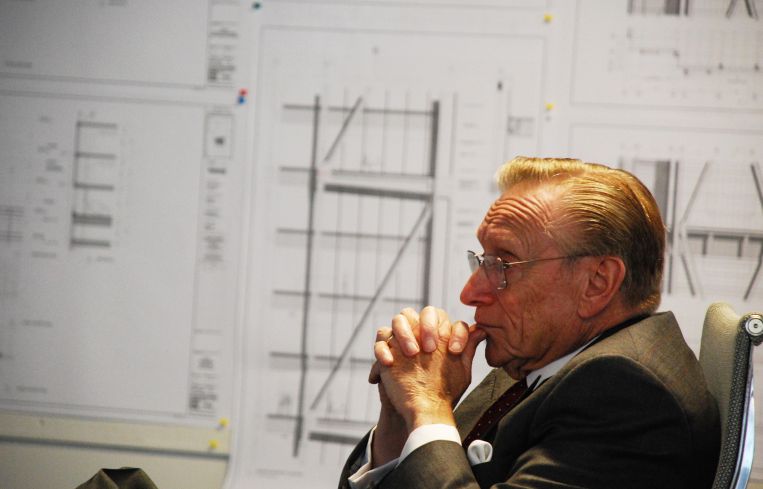

It has taken the city 15 years to semi-recover. But if there was ever a moment for Silverstein to take a victory lap, it is now. (See our second video on WTC today.) When Commercial Observer sat down with him last month at his office at 7 World Trade Center, he had just come from the opening for Eataly, the big Italian market on the third floor of 4 World Trade Center. A few months earlier, Santiago Calatrava’s Oculus transportation hub opened. And looking out 7 WTC’s window one could see Tower 3, the 80-story tower that Silverstein is currently constructing which topped out this year, as well as the Robert A.M. Stern-designed Four Seasons hotel and condominium set to open this month.

To the south is a new raised park and a planned performing arts space, which got a $75 million infusion of funds from Ronald O. Perelman in June. (The design is being revealed tomorrow.) And, of course, 1 World Trade Center stands proudly in the middle of it all, next to the two footprints of the Twin Towers that serves as the harrowing, understated memorial to the victims. (Silverstein is responsible for building all WTC buildings but 1 WTC.)

This is his painkiller.

“The last piece of this entire puzzle will be Tower 2—the final linchpin in the rebuilding of the Trade Center,” said Silverstein, referring to the Bjarke Ingles-designed building, whose fate remains uncertain after a deal to anchor the building with News Corp. and 20th Century Fox went south. “When that building is done, which will be about 2021, my job will be finished here.”

The recovery extended well beyond the World Trade Center; to a large extent, the rest of Lower Manhattan glommed onto this remarkable (and seemingly never-gonna-happen) decade-and-a-half march forward. According to figures from the Alliance for Downtown New York, in the last 10 years, 213 technology, advertising, media and information, or TAMI, tenants have taken some 6.8 million square feet of space in Downtown Manhattan; law, management consulting, design and other professional service companies grabbed another 3.26 million square feet and financial services accounted for another 2.53 million square feet of space leased. In total, a whopping 17.1 million square feet of space has been leased since 2006.

One cannot help but wonder about one of the key players in this whole drama: a now 85-year-old, compact, bespectacled, always immaculately dressed man who grew up in a Brooklyn walkup.

*

Silverstein was born into real estate; his father was a broker leasing manufacturing space in Soho, and Silverstein started working with him while he was still a student at New York University. (Two of Silverstein’s three children also followed their father into the business at Silverstein Properties.)

“It became obvious with time that the best thing to do was to become an owner as opposed to a broker—because the owners were making the money,” Silverstein said. “The brokers weren’t.”

Silverstein looked to what Harry Helmsley and Lawrence Wien had done with the Empire State Building as a model to wheedle his way into ownership. Helmsley and Wien bought the building “with 5,000 investors contributing $5,000 each into the ownership of the building,” said Silverstein, “and somehow they made it work. That’s something we looked at very early on as a means to put our hands around some capital.”

Silverstein started with a derelict building at 220 East 23rd Street that he picked up for $600,000 in 1957, according to Crain’s.

When the first project was successful, “We acquired a second one, and a third one, a fourth. As time went on the buildings got bigger—and suddenly we found the banks were calling us…It was just a matter of time until we gravitated into [constructing] the entire building from the base to the top.”

Silverstein started acquiring land on the Far West Side, near the Port Authority Bus Terminal (where Silver Towers now stands); he picked up properties along Fifth Avenue; and in 1987 he finished construction on a 47-story tower named 7 World Trade Center.

“When he finished 7 World Trade Center, he saw the transportation—the tremendous infrastructure that was already there,” William Rudin, the head of Rudin Management Company, told CO. “And he saw an opportunity to reimagine Downtown.”

A few hundred feet away stood the Twin Towers, for which he acquired a 99-year lease in 2001 at $3.2 billion.

*

“I didn’t want to get involved,” said David Childs the chairman emeritus of Skidmore Owings & Merrill. “But Larry kept pestering me.”

Silverstein had just bought the World Trade Center, and he contacted Childs about any ideas he might have to spruce up the Twin Towers, which Childs hated. The two agreed to meet at the towers, where Silverstein had spent almost every morning since acquiring the property, breakfasting at Windows of the World and meeting with tenants.

On Sept. 10, Childs got a call from Silverstein. The developer couldn’t make their meeting the next day—he had an appointment with the dermatologist that his wife, Klara, wasn’t letting him get out of.

“I got lucky—my life was spared,” Silverstein told CO. “The lives of my children, too, who were on their way to the temporary offices we had in the North Tower. Fifteen minutes later, they would have been there.” (This stroke of incredibly good fortune has been used against Silverstein ever since in the conspiracy-addled corners of cyberspace as proof that he somehow knew about the plot.)

At around 5 p.m. that day, Tighe was walking uptown in a sea of shell-shocked New Yorkers, when she happened to spot Silverstein, and one of his top generals, Geoffrey Wharton, also trekking up Second Avenue.

“I went up to them and started to cry,” said Tighe.

Silverstein put his arms around her.

“Sweetheart,” Silverstein said, hugging her and trying to comfort her, “we’re going to rebuild.”

Indeed, less than half a day after the attack, Larry Silverstein had a good inkling of what his future would look like.

In many ways, Tighe’s memory of that encounter fits pretty well into two prevailing views that have taken shape about Silverstein since 9/11.

Those who know him and like him speak of a warm, optimistic, comforting presence (always asking about kids or grandkids, always willing to extend a hug to those in need). “He’s got a heart of gold,” declared Childs, who designed 1 and 7 WTC. He’s spoken of as a man of grit and determination, an insatiable optimist—always looking to the future.

But for those who do not care for Silverstein (and they are not just the conspiracy theorists), the same story comes out a different way: He was a man in a big hurry, who made up his mind right away without listening to others, without properly grieving for the victims.

John “Janno” Lieber, the president of the World Trade Center Properties, summed it up best in the documentary “16 Acres” about the rebuilding of the site: “Larry was typecast early on in the process as somebody who was fighting about money.”

For Silverstein, it wasn’t callousness, greed or a mad dash for money. There was a larger issue at stake. “The magnitude of the responsibility down here was such that it became my primary responsibility,” said Silverstein. “I felt this was something I had to do—get it done, get it rebuilt as quickly as I possibly could. And do the best damn job that I could.”

But it was probably inevitable that Silverstein was going to be a fraught figure given that he became instantly famous, not just in New York but the world over.

“If I go to China,” Tighe said, “I am asked if I know two people: Donald Trump and Larry Silverstein.”

*

Whether Silverstein wanted to rebuild quickly or not, he probably wouldn’t have had much of a choice.

“Gene McGrath, chairman of Con Edison at the time, called me within a day or two [of 9/11] and told me that he had a terrible problem,” Silverstein recalled. “The Con Ed substation—which provided all the power to Lower Manhattan—was at the base of my building at 7 World Trade Center.” On 9/11, 7 WTC was the last building to fall (and had long been evacuated when it came tumbling down).

“He said we can’t function this way; we’re providing power now with emergency generators. There’s no telling how long that will last, but it’s unreliable and prone to fail…I need you to rebuild that substation quickly.”

Within two weeks of 9/11, Silverstein Properties had its first organizational meeting with architects to rebuild 7 WTC. (It would open in May 2006.)

All the while, Silverstein had his sights set on the whole complex—but he never seemed to abandon the essential sweetness that those around him admired.

The Pritzker Prize-winning architect Jean Nouvel was invited to Silverstein’s office to give his pitch for one of the buildings and found the industry titan not behind a big, imposing desk or hovered over majestic architectural plans. He was on the floor sitting next to Lieber’s 3-year-old daughter, making a paperclip chain.

“Have a seat in my office, Jean,” came the raspy voice of Silverstein. “I’ll be with you in a minute.”

The public witnessed little of this. For anyone who lived in New York City from 2001 to 2006, following the reconstruction of the World Trade Center site was a little like sitting through an extremely long Samuel Beckett play. Nothing happened. Or, at least, very, very little.

It’s true, architectural contests came and went (winner of the master plan: Daniel Libeskind); the various politicos appeared at flag-draped ceremonies at Ground Zero with the families of the victims; and news dribbled out about sniping between Silverstein and the Port Authority of New York & New Jersey, or the governor’s office. All the while, progress at 1 WTC, the then so-called “Freedom Tower,” was hopelessly stunted.

Part of the reason was no two sides could agree on the same vision for the World Trade Center; families of the victims, the mayor’s office, the governor’s office, the fire department, the business community and average New Yorkers all had different agendas.

Silverstein’s toughness served him well during these years—because even his biggest admirers acknowledge that the avuncular Silverstein is hardly all there is to the man.

“Contractors would come in [for World Trade Center work], and he would say to them, ‘This is such an important project—I think you should do it for free,’ ” Childs told CO. “And he was serious.”

“Larry Silverstein is one of the toughest negotiators that I ever met,” said Steven Spinola, the former head of the Real Estate Board of New York and the New York City Public Development Corporation. “Because when I was with the city, I negotiated a deal with him. We never made the deal because both of us refused to budge. But he understood what he needed to do, and he did it.”

The attack begat a multibillion-dollar war with Silverstein’s insurers over whether the two planes hitting the Twin Towers constituted one act or two. (The latter would mean billions more for Silverstein Properties.) And he fought ruthlessly for his side.

“We needed two events,” Silverstein said in the documentary “16 Acres”—almost indifferent to whether his claim was meritorious or not. “Because to rebuild the Trade Center—the cost to rebuild the Trade Center would require not just $3 billion, $3.5 billion—we required more like $7 billion.”

Silverstein’s payout amounted to $4.6 billion in the end, and by 2006 Silverstein came to an agreement with the Port Authority in which he ceded control over 1 WTC in exchange for the right to develop three other skyscrapers. (Silverstein and the Port Authority wound up negotiating again in 2010 to bring down rents, and the Port Authority wound up bringing in the Durst Organization to finish the building and the leasing.)

However, in a crowning touch of irony, Zurich American Insurance Companies, one of the insurers that fought Silverstein tooth-and-nail over his 9/11 claims, wound up taking three floors at 4 WTC this August. “When we first heard they were touring we said, ‘Uh…Oh-kay,” recalled Tighe with a suspicious lilt in her voice. “When we heard they loved it, we said, ‘Uh, Okay.’ ”

As Silverstein himself will acknowledge, his work is not done. The deal that blew up for 2 WTC was a heartbreaker. Rupert Murdoch’s media conglomerate was “going to take about half the building,” Silverstein said. “Two weeks after the beginning of 2016, I got a call from Murdoch. It was a Monday. And he said he was concerned about the state of the world and was not comfortable going ahead with the transaction.

“Was it a disappointment?” Silverstein asked. “Of course. Did we quit? No. Because we never quit until this is done.”

With reporting provided by Terence Cullen.