Coney Island’s Roller Coaster History

By Liam La Guerre July 13, 2016 10:15 am

reprints

Yes, you could call a future Coney Island a comeback—a particularly astonishing one.

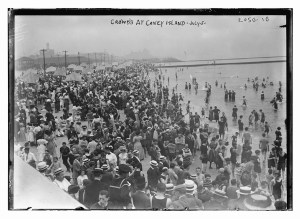

There was a time (from the late 1800s to early 1900s) when almost 100,000 people a day visited the island for rides, races, fights, shows and the beach, of course, according to A Coney Island Reader: Through Dizzy Gates of Illusion, edited by Louis and John Parascandola. It was one of the world’s most popular resorts during its “Golden Era,” attracting hoards of people from New York City, the country and around the world.

“Coney Island has had a lot of nicknames over the years and one of those is the ‘People’s Playground,’ ” said Tom Corsillo, a vice president at Marino Organization, who worked in an advisory role with Central Amusement International, which rebuilt Luna Park in 2010. “It was kind of the place anyone can enjoy.”

There were horseracing tracks, various bathhouses, circus shows and rides galore. From 1897 through 1904, Luna Park, Steeplechase Park and Dreamland amusement parks were all built and competed heavily for customers. The area also featured the Coney Island Athletic Club, a 10,000-seat boxing arena, and the boardwalk opened in 1923. Landmarked Deno’s Wonder Wheel opened in 1920 and the Cyclone roller coaster in 1927. In 1941, the famous Parachute Jump, also known as the “Eiffel Tower of Brooklyn,” was relocated from Queens to its current site behind MCU Park baseball stadium.

While today many associations, like the Coney Island Alliance and the Brooklyn Chamber of Commerce, are advocating for a hotel in Coney Island, hotels were prevalent in the resort dating back to the mid-1800s. There was Green’s Hotel, Manhattan Beach Hotel, the Vanderveers Hotel, Hotel Brighton and the gaudy Elephant Hotel, which was shaped as a giant—you guessed it—elephant and operated a concert hall as well.

The decline of Coney Island started with the closure and sale of the popular Steeplechase Park in 1964 from the Tilyou family to developer Fred Trump (father of Donald Trump, and grandfather-in-law of Commercial Observer Publisher Jared Kushner) for $2.2 million.

But “Coney Island hit rock-bottom around 1975,” native Charles Denson wrote in his book, Coney Island Lost and Found. Around that time, New York City was nearly bankrupt. Competition from other amusement parks and casinos in neighboring states and counties increased. Traveling by plane became more commonplace as well, making it easier to reach other places.

“The ease of ability of travel cut in on the necessity of just staying local,” former Brooklyn Borough President Marty Markowitz told Commercial Observer. “Of course, urban blight certainly had its impact [as well].”

There were various ideas of going the Atlantic City route, and bringing gambling in the 1970s, but that never materialized. And a still recessed New York City didn’t have the funds to pump money into causes to bring Coney Island back to its days of glory.

Declining revenue led to closed storefronts and deserted areas. However, a new era of Coney Island is beginning, and not everyone thinks it will be exactly like it was.

“It can’t go back to what it was—you can only develop what will be,” Markowitz said. “Different era, different time, different expectations.”

![Spanish-language social distancing safety sticker on a concrete footpath stating 'Espere aquí' [Wait here]](https://commercialobserver.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2026/02/footprints-RF-GettyImages-1291244648-WEB.jpg?quality=80&w=355&h=285&crop=1)