Brooklyn and Queens Have Become Hotel Havens. So When Will the Bubble Pop?

By Danielle Balbi and Terence Cullen June 28, 2016 6:05 pm

reprints

Just how bad could Brooklyn and Queens’ hotel oversupply get?

Robert MacKay, the head of tourism for the Queens Economic Development Corporation, has an answer: “Some [hotels] will probably, I hate to say it, be converted into homeless shelters.”

As an example, he pointed to the Verve Hotel, which is located at 40-03 29th Street, just a few blocks away from the Queens Plaza subway station, and near a number of new multifamily developments, including Tishman Speyer and H&R Real Estate Investment Trust’s 1.2-million-square-foot, 1,789-unit rental project.

The six-story property, which was completed in 2007, closed its doors last November to hotel guests and then opened its doors to 200 homeless women.

This doesn’t sound like quite such a fluke, or so ludicrous a prospect when you consider the number of hotel units is about to double in Kings and Queens Counties.

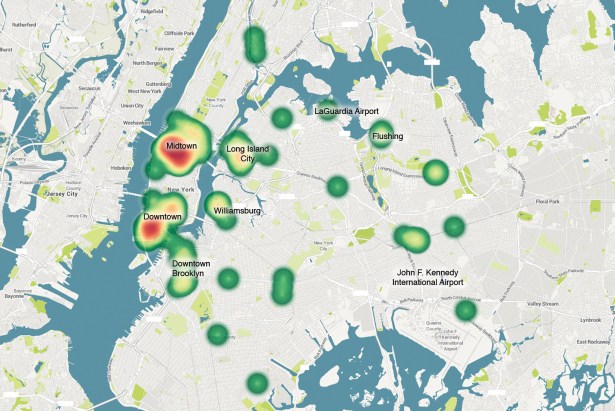

Hotel development in New York City has hit numbers never seen before with 178 hotels and 29,961 rooms currently under development across the five boroughs, according to data from hotel benchmarking firm STR.

While it is little surprise that Manhattan tops the list with a total of 90 projects in the works,

Queens and Brooklyn follow with 48 and 28, respectively. The boom in development will lead to 9,505 rooms in the two boroughs alone, according to STR. A crazier number? That comes out to another 3.5 million room availabilities per year when you multiply the number of rooms by 365 days—meaning the boroughs will be able to accommodate that many more visits over a 12-month period. This will increase the total number of rooms from 6,850 to 16,355 (with a total of 6 million room availabilities per year)—putting the “B-word” (read: “bubble”) in the mouths of the real estate developers especially with concerns that recent economic turmoil will have international visitors planning staycations.

“It’s New York City. We’re always going to have demand,” said Colby Swartz, a managing director at Suzuki Capital, which advises and raises capital for hotel operators. “The supply is really what the concern is.”

And the statistics already show a downward pressure on room rates and occupancy in Brooklyn. While a record amount of both domestic and international tourists have made the trip to New York City since 2009—NYC & Company, the city’s tourism arm, is forecasting 59.7 million visitors in 2016—the revenue per available room, or revPAR, in Brooklyn has seen a year-to-date drop to $112.85 in May from $117.04 in May 2015. Occupancy in Kings County has also declined, dropping to 70.8 percent from 75.1 percent. As of May, the borough has had an average daily rate, or ADR, of $159.48.

While Queens has seen steady occupancy and revenue (anyone who dismisses it as a secondary player in New York’s hotel scene should be reminded about the hotels around LaGuardia Airport and John F. Kennedy International Airport), its revPAR and ADR have been skittish for the last three years. Queens revPAR was $108.82 in May and ADR was $136.84, up 4.3 and 2.4 percent, respectively, from the same time a year ago. But revPAR is still below the high it experienced in May 2013 of $113.68 a night, when ADR was $142.81. The borough has not had rates that high since then.

“I do think that eventually the [Queens] market will saturate,” MacKay told Commercial Observer. “I keep on thinking it’s going to, but then the next day I hear about a new hotel and some of them, like this one that just opened up on Queens Plaza South, the Hilton Garden Inn, opened at 100 percent occupancy. The first week they were 100 percent occupied. The way I see it, eventually [with] some of them, there will be price wars.”

The question then becomes if some of these hotels fail, what happens to them next?

In addition to the Verve, it was reported in May that BKLYN House, at 9 Beaver Street, in the Bushwick neighborhood of Brooklyn, started renting out 44 of its 113 rooms to the city to house the homeless—a month before it even opened.

Things get worse with the United Kingdom’s recent decision to leave the European Union, which sent the British Pound and the Euro into free fall, dropping the pound to the lowest it has been in relation to the dollar since 1985 when Ed Koch was New York City mayor and the last place you wanted to stay was in a Times Square hotel. A strong U.S. dollar against the pound basically means fewer tourists from the United Kingdom—England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland—which accounts for one of the largest demographics visiting Gotham.

“Both the Euro and the pound are likely to be weakest against the U.S. dollar,” said Sean Hennessey, the chief executive officer at Lodging Advisors. “It will make outbound domestic tourism to Europe. We’ll see a significant change in the activity for that part of the tourism sector. I also think by virtue of the U.K. leaving the Eurozone, it increases inefficiencies in the system that the EU was designed to eliminate. It will decrease the amount of disposable income…in a way that would hurt inbound tourism.”

While Manhattan hoteliers are no doubt gnawing on their fingernails as they wait to see how this all plays out, the outer-borough hotel issue is a thornier question. Increasingly, tourists have been staying in the outer boroughs, whether it’s because of a value play or because the Long Island City section of Queens or Downtown Brooklyn are just hipper.

“When you look at the historical perspective, in the late 1990s before the Marriott [Brooklyn Bridge] opened, there were no major hotels in Brooklyn,” said Carlo Scissura, the president of the Brooklyn Chamber of Commerce. “There were a couple of Motor Inns, at best. Now we’re upwards of 40, 50 properties in Brooklyn [with] another 20 to 25 in the pipeline. There are two really signature properties opening in the borough. The William Vale and the One Hotel will transform the way people think of Brooklyn as a hotel place.”

The William Vale hotel, a luxury hotel at 111 North 12th Street in Williamsburg is slated to open at the end of July. The 21-story tower contains 183 rooms, 25 of which are suites, and is located off the Bedford subway station on the L line and just next to Brooklyn Bowl. Nightly rates at The William Vale will start at $350.

“You have to cater to millennials,” said Swartz of Suzuki Capital. They are brand savvy, he noted, so creating a desirable environment and brand recognition will resonate with that demographic and bring those customers back.

“What we are doing is giving a great, local, Williamsburg feel for guests who don’t want to compromise quality and still want to experience a high-end space,” said Sébastien Maingourd, the general manager of The William Vale. “So when it comes to [The] William Vale, I’m not too worried about the supply [of hotels].”

“The connection to the outside makes the hotel unbelievable,” Maingourd noted. Every room will have floor-to-ceiling panoramic views and balconies. There will be 24-hour in-room dining, a fitness center, a 60-foot long pool (which will be the longest in the city), as well as The Vale Park, an elevated, 15,000-square-foot public green space.

Beyond appearance and quality, diversifying a hotel’s offerings is an important driver as well, Swartz said, especially because many hotels in Manhattan and Brooklyn make “a tremendous amount of revenue off of food and beverage.” Having a rooftop and space for events is also helpful, he said.

Indeed, The William Vale will have a heavy focus on its food and beverage package, which is being run by NoHo Hospitality Group and chef Andrew Carmellini. The Westlight rooftop bar will open this summer, and a southern-Italian fare restaurant, Leuca, will open in the fall.

“I have no doubt that those hotels that are either niche, boutique facilities or with a major flag or in the right location will do well,” said Timothy King, the managing partner at Downtown Brooklyn-based brokerage CPEX Real Estate. “I question whether some of the secondary and tertiary locations are going to be here 10 years from now.”

Those secondary areas, which house the discount brands and motor inns of the world, are typically industrial zones that lack the nightlife and infrastructure to draw in out-of-town visitors.

“In some areas, like Gowanus, for example, hotels popped up in unlikely places. But, despite the restrictive zoning, people are converting those industrial properties into retail facilities,” King said. “So there is some night life, there is some reason to support it. There are some that are on side streets in somewhat oddball locations that I think will either have to get to be very competitive in pricing or are going to have some issues with filling the rooms.”

Many of the visitors who would opt to stay in the outer boroughs in the first place are a completely different kind of traveler than the standard tourist.

“If you’re a tourist and you’re deciding to stay in Brooklyn or Queens in a hotel, there’s probably more of a specific reason that you’re coming to New York City, versus if you’ve never been here, you’re probably looking at a hotspot in Manhattan, like Times Square,” Swartz said.

Brooklyn Airbnb host Richelle Burnett, who rents out a two-bedroom apartment in her brownstone in Bedford-Stuyvesant, told CO that many of her guests are families from out of town who are visiting their children and siblings who have moved to the neighborhood and can’t afford to pay “astronomical amounts to stay in the [Manhattan]” for extended periods of time.

She has been renting out a top-floor unit on Airbnb since 2014 and said that at the very least, it’s occupied for half of the month. Burnett currently lists the space for $170 per night, a price she determined by finding a “happy medium” between rents in her neighborhood and nightly rates at hotels. She noted that her guests love having an entire two-bedroom apartment to themselves and that she’s able to create a more intimate experience for them. Last month, she decorated the hallway with signs for her visitors who were celebrating their daughter’s graduation.

“We know that Airbnb travelers are looking to see their destination through the eyes of a local,” said Josh Meltzer, the head of New York Public Policy for Airbnb. “When our guests choose to stay with hosts outside of Manhattan, they are also helping New Yorkers pay their bills and neighborhoods businesses stay open. [It’s] money that stays in the city and helps neighborhood economies thrive.”

The extent to which Airbnb will affect the hotel market in the boroughs remains unclear, though, in part because of legality issues. Year-to-date, hosts in New York City made $459 million, according to the company, compared to the $8.8 billion in revenue seen across hotels in New York City, with the exception of the Bronx.

“There is something for everyone in Brooklyn. If you want high-end, middle, or a little bit on the lower-priced scale,” said Scissura, “you can find [it]. If you want boutique, if you want Sheraton, Marriott, you have that. Or if you want a cool, interesting hotel, like the Wythe in Williamsburg, you’ve got that also.”

And while the diversification of the Brooklyn (and Queens) hotel markets offers visitors different points of entry when it comes to cost, the overall number rooms yet to come online across the entire city cannot be ignored.

“Additional rooms still to be opened in Manhattan are going to add to the pressure of Brooklyn and Queens,” Hennessey said. “In the same way that new hotels in Brooklyn and Queens will probably hasten the economic deterioration of the older hotels in that market, the same thing happens every time another five new tourist hotels open in Manhattan. There’s a bit of an impact where customers who might have stayed in Brooklyn or Queens to get a better deal now can get a comparable deal or bargain by staying in Manhattan.”