A Farewell to Fairway: The Rise and Fall of a NYC Institution

By Larry Getlen May 19, 2016 9:30 am

reprints

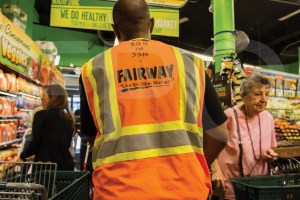

For a certain kind of New Yorker, Fairway Market was as much a status symbol as it was a place to pick up an imported cheese on the way home. (Yes, for the Fairway faithful, its assortment of cheeses is unmatched.) It was quite simply the Upper West Side’s greatest grocery store—leaps and bounds beyond anything on offer by KeyFood. When Fairway replicants cropped up in Red Hook and Harlem, real estate brokers touted it as all the proof needed that the neighborhood was livable.

The grocer, which filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection this month, offered an almost-unprecedented assortment of food in one place, and a comfortable setting in which to buy them. You might say they were Whole Foods, before Whole Foods. (If Whole Foods weren’t so distracted with terms like “organic” and “sustainable.”)

But the chain that once hoped to open 30 to 35 stores in New York City alone put those plans on hold as its financial world collapsed, taken down by both brick and mortar and online competition, a poorly-planned expansion that devastated its own stores (among other troubles) and an ill-advised initial public offering, or IPO.

Opened in 1933 by Nathan Glickberg, Fairway spent its first several decades as a simple Upper West Side fruit-and-vegetable stand before expanding to become a full-on grocer, at Broadway and West 74th Street, in 1954. (This was when it took on the name Fairway). Run by Nathan and his son, Leo, Fairway spent the next two decades as a popular local store with only four cash registers, offering solid deals on fruit, vegetables and penny candy.

Leo’s son Howie came aboard in 1974 with dreams of expansion. Along with partners Harold Seybert and David Sneddon, Howie Glickberg launched Fairway’s next phase, according to Fairway’s website.

They began offering a greater assortment of goods, seeking out exotic, hard-to-find items. By the 1980s, they expanded into the space next door (the current address is 2131 Broadway).

Fairway opened its second location in Harlem, at 2328 12th Avenue between West 132nd and West 133rd Streets, in 1995. The new store, which features a “Cold Room” with vast offerings of meat and more, grew so popular that The New York Times once called shopping there “a test of endurance.”

The slow, measured expansion rolled on, with its first Long Island store opening in 2001, and its massive Red Hook, Brooklyn branch following in 2006. As Fairway’s popularity spread, it was clear that the store was offering not just great products, but a more fulfilling shopping experience.

“They brought an attitude to retailing that was unique,” said Jon Springer, a reporter for the food distribution trade publication Supermarket News. “They had a brashness, an energy and a charisma you wouldn’t associate with chain retailers. Fairway demonstrated that food could be fun and exciting. It didn’t have to be a drudge trip to a boring parking lot.”

In 2007, with his partners ready to retire, Howie Glickberg recruited Sterling Investment Partners, a Westport, Conn.-based private equity firm, to help expand the chain. Sterling, which had never operated in the grocery industry, took an 80 percent ownership in Fairway with a $150 million investment, and new stores began appearing at a brisk pace, with at least one—sometimes as many as three—opening every year between 2009 and 2014. In addition to the city, Fairway branched further into the suburbs, opening stores in New Jersey, Westchester and Connecticut.

When the chain opened its two-story, over 40,000-square-foot Upper East Side location in July 2011, Howie Glickberg told The Wall Street Journal that the new store would bring a touch of the suburbs to the city, citing its wider aisles, and calling it a “nicer experience than your typical New York City store.” Charles Santoro, Sterling’s managing partner, told the paper the stores then did about “$550 million in sales,” with expectations of surpassing $1 billion by the end of 2012.

But in planning its massive expansion and then taking itself public, Fairway overreached.

In a prospectus filed with the SEC in September 2012 by Fairway Group Holdings Corp., the company declared the intent—based on two distinct store models: one urban, one suburban—to open “three to four stores” annually in the Greater New York metropolitan area, “primarily in suburban locations.” Over time, the plan called for “up to 90 stores” in the Northeast, and “more than 300 additional stores” throughout the U.S.

When the company went public in April 2013, shares rose 33 percent on the stock’s first day and, according to Fortune, “surged an additional 60 percent over the next three months.” At its peak, the magazine noted, Fairway was valued at “a little over $835 million,” or “$75 million per existing store at the time.” That August, the company announced that Fairway would be the anchor grocer for Hudson Yards, with a site of over 45,000 square feet residing on the ground floor of the new neighborhood’s 52-story South Tower, next to the High Line.

*

It soon became clear, though, that the IPO and the expansion had been poorly-timed and ill-planned.

After reaching a high of $28 a share in July 2013, according to Crain’s New York Business, the stock price plummeted to just $3.76 by September 2014, and would continue to fall over the coming year. Shareholders filed lawsuits, alleging misleading financial information, and the company cycled through three chief executive officers in one year. Current company head, Jack Murphy, the co-founder of Fresh Fields, came aboard in September 2014. (Fairway did not directly comment for this story but directed Commercial Observer to past disclosure statements.)

Competitors Trader Joe’s, which opened an Upper West Side location in 2010, and Whole Foods, which set up shop in Gowanus and the Upper East Side in 2013 and 2015, respectively, cut into Fairway’s sales in these neighborhoods. Fresh Direct and other new grocery delivery services did the same online.

Plus, Fairway’s suburban stores didn’t take off as hoped—and the company even cannibalized itself, with revenues from new stores taking business from some of their long-standing establishments.

For some time after the IPO, it seemed that every story about Fairway concerned its dire financial state, as reporters gleefully compared the company’s stock price to the cost of produce or dairy items from its stores.

In addition to poor planning and increased competition, the chain also faced bad luck. Superstorm Sandy forced its Red Hook store at 480 Van Brunt Street to close for 16 weeks in 2012, during a period when, according to Bloomberg News, it had earned $25 million in sales the previous year. The store then reopened just in time to face new competition from the nearby Whole Foods in Gowanus, at 214 3rd Street, which opened soon after.

Add in the increased availability of specialty, formerly hard-to-find food items in large stores like Costco and smaller retailers throughout the city, and Fairway’s uniqueness melted away along with its profitability and the value of its stock.

“Fairway was cool when the Upper West was frugal and rent-stabilized,” said Chase Welles, executive vice president of SCG Retail (which represents Whole Foods) in an email to Commercial Observer. “Now, the retail environment reflects the evolved tastes of the original Fairway shopper’s children—it is much more fashionable and affluent. Shopping—for anything—is much more a lifestyle choice, and today’s New Yorker no longer embraces the lifestyle of peasant skirts and hissing radiators. Fairway exported a style that was out of style. Fairway made the mistake many retailers make—they expected the customer to bend to their presentation—and there are simply too many good options in New York.”

John Catsimatidis, owner of the Red Apple Group, said that people in the supermarket industry “couldn’t believe what was going on” with “the amount of cost to open up these stores, the amount of margins they were working on, and the amount of payroll they were spending to run the stores.”

“They built a beautiful store, but nobody was watching the expenses,” said Mr. Catsimatidis, who owns the Gristedes stores. “It’s very hard for hedge funds to own food companies, because with food companies, you have to be very patient. There’s no instantaneous profit. There is profit there, but you have to grind it out. It takes time. The old-timers say, ‘you’ve got to watch your pennies.’ ”

In October 2014, CO reported that Fairway was looking to bail on a lease it had signed for a 52,242-square-foot, two-story space at 255 Greenwich Street in the Financial District, adjacent to the 9/11 Memorial, because “they don’t have the money to build,” according to a source. It would have been the chain’s first store in Lower Manhattan. The following spring marked the end of its Hudson Yards hopes as well, as Fairway paid $3.5 million to terminate the lease.

That same month, Bloomberg ran a piece noting that, while the company’s value had “plunged 77 percent” since the IPO, its directors took home $12.1 million, an amount equaling “the combined boards of Apple Inc., Google Inc. and AT&T Inc., which have an aggregate market capitalization of $1.2 trillion.” Fairway’s, by comparison, was then $132 million. One analyst noted in the story that “it’s certainly a lot of money for directors that have not really directed any value creation.”

By October 2015, the Times was reporting that Sterling’s acquisition “has contributed to a heavy debt load of $250 million,” and that Fairway had abandoned its comprehensive East Coast expansion strategy to instead “flood the boroughs” with stores. The company had not reported one profitable quarter since the IPO.

Last month, Bloomberg reported that Fairway “received two warnings about being delisted from the Nasdaq Stock Market for failing to maintain a minimum market capitalization of $15 million for three consecutive business days.” On April 15, its stock price was down to a mere 39 cents. Shortly before this, an unnamed buyer for the chain told Grub Street of the chain’s collapse, “Lives have been totally changed and ruined. What happened was an injustice.” (The writer of the article was a former Fairway employee who noted that during the expansion, “the place was kind of a mess,” and that at times, it took “months to get paid.”)

Finally, earlier this month, Fairway filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection, seeing its stock drop to 7 cents per share on the news, its market value a paltry $11 million. It had lost more than $500 million in equity value since the IPO.

Fairway put a prepackaged financial restructuring in place that will see it cast off $140 million of senior secured debt and obtain $55 million in financing, with lenders exchanging a portion of their debt for common equity. The company said that no stores will close, and that there will be “no interruptions to customer service throughout the process.”

Mr. Catsimatidis believes that for Fairway to eventually be profitable again in New York, it will have to close some stores, and that if it pairs with outside buyers again, it has to be with a company with far greater knowledge of their industry.

“They have to trim down the operation—keep their profitable stores, get rid of the unprofitable stores,” he told CO.

“They have some good locations, but it can’t be a hedge fund that buys them. It can’t be a management firm. It has to be a supermarket operation that understands how to run supermarkets.”