Take a Gander at Gansevoort

By Harry Kendall March 23, 2016 10:15 am

reprints

What makes a building or neighborhood historic? How do we determine what is worth preserving, and to what extent? And in a city with such a deep, rich history, how do we weigh one period of significance against another?

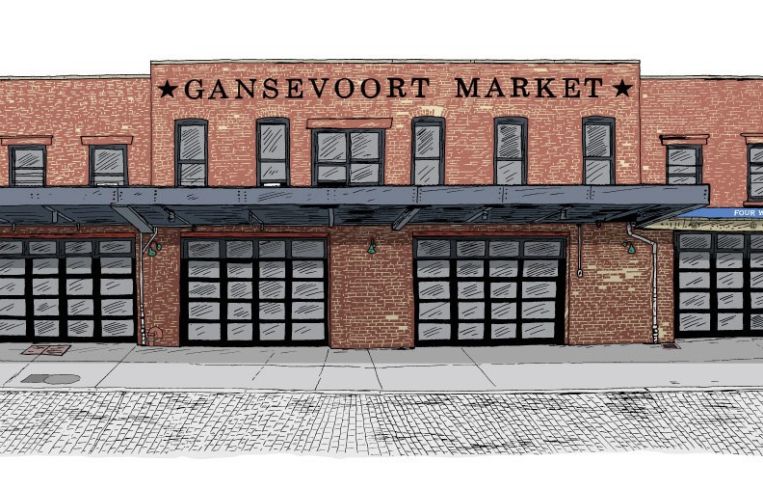

The Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) can be a riveting public forum for such questions, with robust discussion about urban change, public good and historic district “appropriateness.” Currently under consideration on Gansevoort Street are proposed changes to a group of five buildings that comprise a full block front from Greenwich to Washington Streets. The issues raised are compelling and relate very much to the uniqueness of the Gansevoort Market Historic District, named for the open-air market that operated just one block from the project site during the 19th and early 20th centuries.

The block in question is notably low-scale with only two-story and one-story existing structures. Yet, from the 1880s through the 1920s when the nearby Gansevoort Market represented the lifeblood of the neighborhood, this block held a group of mostly five-story buildings. Some of the buildings that stand today are fragments of these taller buildings, altered for a number of reasons in the ensuing decades.

Renderings of the new block-long design show preserved portions of the existing fabric with the most architecturally and historically significant of the two-story buildings remaining at their current height. They also reference earlier incarnations of the block with new four-, five- and six-story street walls that reflect earlier periods of historical significance. The architectural language is restrained, yet establishes a clear sense of contemporary dialogue with the site’s history and with wider district building types.

To many, including this writer, the proposed combination of restoration and new architecture seems a marked improvement to the existing conditions, especially in the way the district’s varied past is mined for inspiration. To others, the existing uniform scale of this one block seems to be a quality worthy of preservation. That sentiment is understandable but is at odds with the spirit of several nearby LPC-approved projects.

Indeed, the Landmark Commission’s own designation report highlights the “architectural change and flexibility that has shaped the character of the…Historic District.” The report identifies multiple periods of significance, which has been interpreted as something of a mandate to continue the district’s evolution. The Diane von Furstenberg Studio Headquarters on West 14th Street and Washington Street, the so-called “twist” building at Washington Street and West 13th Street, and the forthcoming two-story addition at 9-19 Ninth Avenue are among the Gansevoort Market projects unlikely to have been approved elsewhere. Each of these examples includes a dynamic juxtaposition of historic and contemporary architecture. Taken together they represent a vibrant sector of NYC whose character has been successfully protected by landmark regulations without diminishing the district’s sense of innovation. Close at hand, the High Line elevated park is another compelling example of a stunning transformation, both sensitive yet daring.

We believe the proposed changes to 46 to 74 Gansevoort Street are similarly forward-looking and appropriate. We are confident this block will ultimately be celebrated as another example of the Landmark Commission’s enlightened treatment of the Gansevoort Market Historic District. This neighborhood, like New York City, has not one history but many histories, and this project is a reflection of that.

Harry Kendall is a partner at BKSK Architects.