Why LaGuardia’s Central Terminal Costs $5.3 Billion

By Terence Cullen March 23, 2016 3:18 pm

reprints

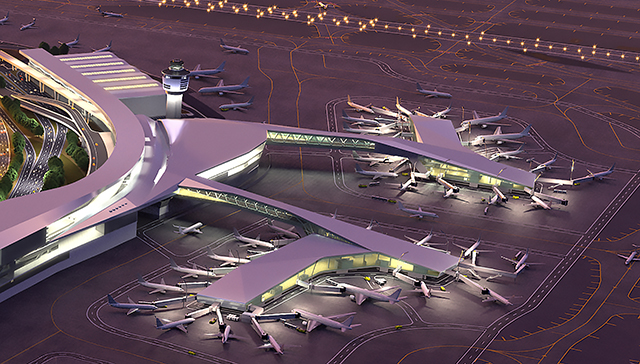

Tomorrow could be a big day for LaGuardia Airport: board members of the Port Authority of New York & New Jersey, which controls the airport, is set to vote on the $4.2 billion project to build a new central terminal, otherwise known as Terminal B. If approved, the vote effectively greenlights the ability for LaGuardia Gateway Partners—a consortium of six developers, architects and managers—to build a new terminal and manage the property for the coming decades.

But the project raised eyebrows last week when the agenda for this month’s board meeting was released. In the document, the project is forecasted to cost $5.3 billion when you fold in work at the airport between 2004 and last month. Even when you take out that additional $1.1 billion of capital improvements, the cost of rebuilding the central terminal has been escalation. The estimate last month was that a new structure would cost $4.2 billion was a 17 percent increase from the 2014 estimate of $3.6 billion, as The Wall Street Journal reported.

Because some of the cost stretches back more than a decade on work that’s already been done, the new price tag doesn’t solely represent the amount for building a new Terminal B, said Richard Anderson, the president of the New York Building Congress.

“It’s not necessarily apples and apples to compare it with the original” estimate, Mr. Anderson said. “They need to approve it regardless of the price. This is the country’s largest metropolitan economy and we’re limping with a third-rate airport. It’s severely overdue.”

Naturally, that’s a high number for a portion of the smaller and non-international of the city’s airports. But before anyone hits the panic button about a terminal that will cost the same as the recent sales price of Stuyvesant Town-Peter Cooper Village, let’s take a look at all of the things that go into the project, which is slated for completion somewhere around 2020.

[googleapps domain=”docs” dir=”spreadsheets/d/17FMEYXLVHXyAXnY67N0AUd7limmO_S03fQs403x4ZRI/pubchart” query=”oid=1681973524&format=interactive” width=”854″ height=”528″ /]What goes into rebuilding a quarter of one of the nation’s busiest airports? For starters, it’s the building itself, which is where most of LaGuardia Gateway Partners’ $1.8 billion will go, according to the Port Authority. The agency will cover the other $1 billion associated with the structure via a passenger facility charge—essentially a tax attached to flights that fund infrastructure approved by the Federal Aviation Administration. Those are capped at $18 per round trip ticket, according to the FAA. The third-largest piece of the pie goes toward supporting infrastructure—roads, for example—which will cost $856 million.

Next is the new central hall, for which the Port Authority is set to pay $310 million, and which LaGuardia Gateway Partners will shell out $34 million for over a seven-year period. Staff costs for members of the Port Authority will be $225 million; third-party consultants and agreements are estimated to be $259.6 million; a reserve fund for the airport is being set up to the tune of $182 million.

Rounding out that hefty $5.3 billion figure is capital improvement work done over the last 12 years, which has cost the Port Authority just shy of $605 million.

[googleapps domain=”docs” dir=”spreadsheets/d/17FMEYXLVHXyAXnY67N0AUd7limmO_S03fQs403x4ZRI/pubchart” query=”oid=968647809&format=interactive” width=”874″ height=”540″ /]If the project gets approved, the Port Authority would cover $3.5 billion of the overall project, while LaGuardia Gateway Partners is shelling out $1.8 billion for the design and construction of the terminal, according to the agenda. As part of the agreement, LaGuardia Gateway Partners would maintain the property and make back its money by collecting fees from the airlines using the terminal as well as rent from potential retail tenants.

[googleapps domain=”docs” dir=”spreadsheets/d/17FMEYXLVHXyAXnY67N0AUd7limmO_S03fQs403x4ZRI/pubchart” query=”oid=2119860686&format=interactive” width=”592″ height=”366″ /]In 2014, about 13.5 million people walked through Terminal B—about half the 26.9 million travelers that went through all four of LaGuardia’s terminals, according to data from the Port Authority. The agency expects that more than 17 million people will travel through the terminal by 2030, which is a 1.5 percent growth every year over the next decade and a half. By the same metric, LaGuardia as a whole will have 34 million people in 2030.

So, aside from Vice President Joseph Biden making the airport the butt of infrastructure votes, why does this project matter so much to the Port Authority and real estate players who want people to visit New York for business or pleasure? Well, for starters, the current Terminal B was built in 1964. At the time, it was only expected to handle 8 million people per year, according to the Port Authority. The terminal was upgraded and expanded in the 1990s to 835,000 square feet from 750,000 square feet.

“When the Vice President of the United States comes to town and says, ‘I feel like I’m entering the Third World, instead of the greatest city in the universe,’ you have the greatest description of all descriptions,” said Barry LePatner, a construction attorney and advocate for infrastructure investment. “Why is it lousy? Because it’s more than lousy: it’s long overdue for bringing it to the 21st Century.”

Joseph Sitt, the head of Thor Equities and founder of airport redevelopment group Global Gateway Alliance, said in prepared remarks that while tomorrow’s vote was a step in the right direction, he urged the bi-state agency to keep the project on time and not inflate the already sizeable budget.

“The Port Authority is taking an important first step by presenting realistic project costs, but now it is essential that the agency stick to them,” Mr. Sitt said. “We are urging the Port to outline clear budgets and time frames, and increase public transparency to ensure it doesn’t fall into the same traps of cost overruns and project delays.”