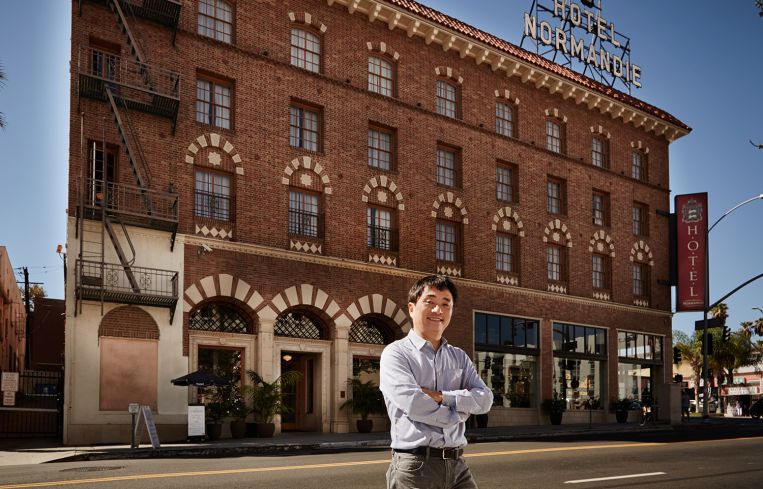

Jingbo Lou: The Accidental Hotelier

By Michael Kaplan October 8, 2015 1:08 pm

reprints

Jingbo Lou did it for love. Why else would an ordinarily rational architect from Pasadena, Calif., buy a 1926 Renaissance-style hotel loaded with drug addicts and prostitutes and situated on a dodgy stretch of downtown Los Angeles’s pre-gentrified Koreatown? The property, after all, had been hanging in foreclosure and was ultimately bailed on by the previous owner, who had brought Mr. Lou in for architectural consulting.

It started in March of 2011 with a call from a remote relative of Mr. Lou’s wife who worked as a real estate broker. The relative was looking to negotiate a deal for a local investor who wanted to purchase the decrepit and poorly located Hotel Normandie, rename it the 420 and—pending the legalization of marijuana in California—turn the structure into the state’s first pot-friendly hotel.

“My wife’s relative told me nothing about the Normandie,” Mr. Lou recalled in an interview with Commercial Observer. “But when I first walked in and saw the ceiling height, the chandeliers, the columns, a wood-burning fireplace in the lobby, the grandness of it all, I knew it could be something special.”

Never mind that the place reeked of sewage and pot, while layers of wallpaper covered layers of wallpaper, ceiling beams had been painted sickly shades of yellow, and the front windows were slathered over with drywall.

Mr. Lou’s wife’s relative wanted him to tell the potential buyer and his broker that it could be renovated for $500,000. But Mr. Lou, being honest, told them that the total cost would be closer to $5 million. After hearing that number, his relative seethed and the potential investor moved on.

“I asked if I could make a bid on it,” said Mr. Lou, who, in turn, received an introduction to the property’s note-holder, a private lending institute called Mortgage Income Fund that is based in Orange County. “The bank told me that I need $100,000 to start escrow and $4.5 million to buy the property. I don’t have that kind of money, but my brother does. He’s a very successful tech entrepreneur. I asked to borrow $100,000 and he wired it to me. I needed to lock in the deal.” That was two weeks after Mr. Lou first saw the property.

Two months later, in May of 2011, he raised an additional $2 million from a pair of Chinese acquaintances who hoped to take advantage of the EB-5 Immigrant Investor Program, which provides U.S. visas to foreigners who invest $500,000 to $1 million for projects that create jobs. As for the rest of the money, Mr. Lou took an even less conventional route.

Over the next three years, he said, “I squeezed my brother for an additional $2 million and borrowed $2.5 million from [Mortgage Income Fund] so that I could begin renovation work,” he said. “I knew I would be the architect, general contractor, developer. I’d wear all the hats, work six days a week, and put in 15 hours per day. People told me that I had a zero-percent chance of succeeding. Friends begged me not to do this. I knew I was putting my life on the line.”

As a first-time hotel owner, renovating a neglected property in an undesirable neighborhood, Mr. Lou was fortunate to have hustled up what eventually turned out to be $13.5 million (between two restaurants he wound up adding and his decision to preserve more detail than anticipated, Mr. Lou saw the budget rise $4 million beyond what he had initially expected). Additional funds came after he partnered with outside investors, and, in some cases, Mr. Lou needed their approval to move forward.

Considering the scope of the project, Daniel Peek, head of the hospitality group at the national brokerage firm HFF, described the Normandie undertaking as being at the far end of independent.

“There is good liquidity for brand-name developers,” Mr. Peek told Commercial Observer. “But the truly independent projects can be hard to underwrite. [Mr. Lou] practically did crowdfunding with friends and family. Often that’s how independent developers get started. Once they prove the model, then they can go mainstream and get traditional funding.”

Armed with his cobbled-together bankroll, Mr. Lou embarked on a massive overhaul that spared all of the Normandie’s good parts. Those included beautiful wooden beams that now stripe the lobby’s ceiling, an ornate facade, distinct neon signage on the roof, and 13-foot ceilings in the 103 guest rooms (only 36 of which were operational when Mr. Lou bought the place).

The property’s new owner used a heat gun to slowly remove layers of paint on the inside of the hotel without disturbing the wood-finishes below. During that time, he oversaw a work crew that would grow to as many as 50 people on busy days. The trickiest part of the renovation, however, was getting rid of undesirable squatters and low-paying tenants that lived there, he said. Some used the building as a drug den and at least one resident occupied two rooms that served as a brothel.

“I saw naked girls getting locked out of the rooms,” Mr. Lou said, emphasizing that he did his best to apply a soft touch to the eviction process. “I asked people what it would take for them to move out. Some left for $500. One guy was tough; it took $20,000 to get him out. But eventually they all left.”

Then he got a little lucky when the Sydell Group, owners of the cushy NoMad Hotel in Manhattan and the Freehand in Miami, decided to team up with the popular chef Roy Choi on the Line Hotel—just a couple of blocks away. Suddenly the neglected neighborhood had a new sheen, complete with hip restaurants, spas, shops, and craft cocktail joints. “The Sydell guys came to me and wanted to buy my building,” Mr. Lou recalled, vaguely aware that the Freehand is a chic hostel of sorts (the kind that gets written up in Vogue and GQ).

“They said they wanted to create rooms with bunk beds in them or something. I don’t know what they had in mind, but I knew it wasn’t what I wanted to have done here.” The Sydell Group pressed Mr. Lou for a selling price. “So I gave them something ridiculous,” he said. “$18 million.” The prospective buyers walked. Through a spokesperson, the Sydell Group has chosen not to comment on this.

Lacking a collaborator like Roy Choi, Mr. Lou had no idea as to what would anchor the Normandie in terms of food and drink. The inexperienced hotel owner ate many of his meals at Subway and viewed leisurely dinners as time-wasters. Yet, something told him that it made sense to buy the name, signage and cooking equipment from Cassell’s Hamburgers, located near the Normandie. Hobbling along on shaky legs, selling just 30 burgers a day, the once-robust restaurant was let go for what Mr. Lou describes as “the cost of a good BMW.” He bought the business, but not the lease, and relocated Cassell’s to a street-facing corner of his hotel.

Mr. Lou anticipated reviving the neighborhood burger joint that had dropped from favor with all but its most loyal customers. To bring it back, he hired Christian Page to be the chef; considering that Mr. Page had previously worked at Nancy Silverton’s highly regarded gourmet burger spot Short Order, getting him was a bit of coup. Mr. Page went on to elevate Cassell’s to a whole other level—just as Mr. Lou was doing with the Normandie itself.

With his casual eatery in place, Mr. Lou mentioned to a foodie friend that he wanted to check out some good restaurants in the hopes of learning more about fine dining and perhaps finding himself a chef who could helm what would eventually be the Normandie’s signature restaurant—an upscale, dinner-only operation that would complement Cassell’s, which serves throughout the day and into the night.

The first place Mr. Lou and his friend went to was one of chef Gary Menes’ acclaimed pop-ups. Mr. Lou loved it and wound up hitting a couple dozen of Mr. Menes’ “catch-them-if-you-can” dinners. Somewhere in the course of that, he made an oddball proposition to Mr. Menes. “I told him that I wanted to learn about food,” Mr. Lou said. “The deal was that he would take me to his favorite restaurants and educate me. We went to places like Animal, Test Kitchen and Son of a Gun. Instead of paying tuition, I paid for the meals.”

It had nothing to do with Mr. Lou getting Mr. Menes to open a restaurant inside his hotel; it was about a desire to learn. The two men—Mr. Menes painfully taciturn, Mr. Lou gregarious—became unlikely friends. As Hotel Normandie neared completion, Mr. Menes became enamored with the idea of growing his own produce for a restaurant with just 12 seats along a single counter. It became especially appealing after Mr. Lou sweetened the deal for what ultimately became the well-reviewed Le Comptoir.

“I charge Gary low rent and helped him build the restaurant,” said Mr. Lou. “He had limited funds, so I paid 75 percent of the build-out. But now we have a destination and a restaurant that is all about Gary.”

As for Mr. Lou’s frequent meals at Subway, he no longer eats there. “My chefs would kill me,” he said. “They’ve told me that Subway’s food is garbage.”

When it came time to outfit the Normandie with a stellar barman, Mr. Lou connected with Cedd Moses, known for downtown L.A.’s The Varnish, a stylish speakeasy-style bar hidden behind the venerable Coles restaurant (famous for its French dip sandwiches). Mr. Lou reached out to Mr. Moses via a blind email. “Cedd got right back to me,” the newly minted hotelier recalled. “Turns out that he was looking for a place in Koreatown.” With that, the elegant, cocktail bar Normandie Club was born.

When it came to planning the guest-rooms, Mr. Lou said he wanted to stay true to tradition. “The wood floors were there; the doors and windows were there,” he says. “Getting new doors would have been cheaper than fixing up the old ones. But I wanted to tell a story, and that meant keeping all the old stuff.”

Coming off as a bit of an accidental hotelier, Mr. Lou fully launched the refurbished Hotel Normandie in January of 2015. Since then, the boutique hotel, which has never closed since its debut in 1926, has become enough of a success that booking last-minute reservations over the summer presented a challenge for spontaneous guests.

“Hotel Normandie is a project that came to me; I had to do it,” Mr. Lou said. “Tearing the building down would have been a better business decision. But it would not have been better for the city of Los Angeles or for me. I am a new urbanist at heart.”

He’s also developing a knack for juggling funds. In 2013, Mr. Lou refinanced his borrowed money—which came from himself and his brother as well as Mortgage Income Fund—with a $5 million Small Business Association loan from New Omni Bank in Los Angeles. That paid back $3 million in borrowed money and provided $2 million to finish the job. Ultimately, Mr. Lou wound up with nine investors (individuals who put up as little as $25,000 and as much as $2.2 million, and real estate holding company McKinley Investment).

He now maintains a 37-percent ownership stake in Hotel Normandie—making him the majority owner—and he has the satisfaction of proving countless naysayers wrong. Mr. Lou bragged about being turned down by several lenders and management companies throughout the course of the renovation project. Broughton Hospitality Group now runs the hotel’s day-to-day operations and Mr. Lou noted that some other potential partners have tried to save face by claiming he rejected them.

With Hotel Normandie humming along and back to its original splendor, the do-it-yourself architect and real estate owner is now working on a mixed-use development with commercial space, artists’ lofts and a grocery store inspired by Whole Foods located on Wilshire Boulevard and Catalina Avenue—right near the old Ambassador Hotel, where Robert F. Kennedy was assassinated. That project is being done with one of Mr. Lou’s current investment partners and Mr. Lou will own about 27 percent of the finished property, he said.

Nevertheless, Mr. Lou remains entirely modest about revitalizing a dilapidated and distressed hotel without any major branding or initial support from an institutional lender. “What’s important is that Hotel Normandie finally got recognized,” he insisted. “I get to tag along with it, and that is a good feeling.”