We have heard a lot lately about undesirable characters from overseas who come to the United States—particularly Manhattan—and buy very expensive residential real estate in a handful of projects targeted to billionaire buyers. Typically these purchasers, it is said, will live in their expensive new residences no more than a couple of weeks a year.

Instead, they use their Manhattan investments largely as a mechanism to store value—sort of like a safety deposit box or buying a Van Gogh and sticking it in the basement for a couple of decades, or today’s version of a Swiss bank account. Some of these purchasers may also use New York real estate to launder or conceal ill-gotten funds from abroad.

In most cases, these buyers set up new limited liability companies to hide the ultimate ownership of the apartments they buy. No public document offers any clue of who owns that LLC. By using these “shell companies” to establish a “cloak of secrecy,” these alleged bad guys stay invisible. This, it is said, is a bad thing, because real estate ownership should be public and transparent to anyone who wants to write an article about who owns what.

My own recent inquiries do confirm that it is difficult or impossible for an ordinary citizen (or lawyer, or reporter) to find out who owns a particular LLC of this type. A private investigator friend told me the best way to get such information, at least outside of litigation, is to find a disgruntled former spouse or employee, and have them spill the beans—though first you have to know where to look. So the cloak of secrecy works, though tax collectors and criminal investigators may have ways to pierce through it after the fact.

The criticism of certain foreign buyers buying expensive apartments with possibly ill-gotten gains also typically includes a suggestion that developers, sellers, lawyers and brokers shouldn’t participate in sales to them. In other words, these transaction participants should somehow evaluate the moral standards and possible disreputable history of any would-be purchaser. If that particular purchaser is not determined to be saintly enough, then they should not be allowed to buy. The apartment should be sold to someone else.

As their subtext, these criticisms often make two suggestions. First, they suggest that the entire residential real estate industry should be subject to regulatory burdens like those in the banking industry, i.e., a requirement to investigate purchasers and not do business with disreputable ones. Second, they suggest that ownership information about “shell companies” should be publicly available. But before our omniscient and sometimes overactive federal government takes either of those steps, we should step back a bit and consider the big picture.

We have traditionally considered privacy a good thing, not a bad thing. Variations on that concept appear in the constitution and throughout constitutional law and our legal system. Not all information must be public. Purchasers of high-end real estate (as well as anything else) have perfectly good and valid reasons to not want the world to know what they own. Why is the world entitled to know who owns an LLC? Tax and other governmental authorities may be a different matter. If they aren’t getting the information they need to enforce our existing laws, then perhaps they should collect more information. But they should do it with as little burden on legitimate players as possible. And the information collected should remain private.

As a matter of common practice, we do use newly formed companies, with no other assets, as the vehicle for just about every commercial real estate transaction and for many substantial residential ones. We do this for many good reasons, including accounting, asset protection, estate planning, income tax planning, lender requirements, liability protection, privacy, protection from oppressive regimes (for some offshore purchasers), safety, security and transferability. Wealthy or prominent purchasers, domestic or foreign, often care a lot about many of these concerns, and legitimately so. They are targets.

Developers, lawyers, brokers and sellers are ill equipped to investigate and evaluate the saintliness of contemplated purchasers. If the federal government lets those people into the country, and if the banking system already to some degree keeps an eye on “bad guys” wiring money into U.S. bank accounts, it seems unreasonable to expect private players to perform an additional vetting function. Every substantial closing involves wire transfers through banks. It should be possible to build into that system whatever level of checking makes sense, if it isn’t already happening. Banks have already implemented extensive Know Your Customer rules. Those KYC rules don’t always apply to wire transfers into lawyers’ trust accounts, but could—with significantly less burden than if every lawyer, developer, broker or seller had some obligation to investigate every purchaser.

If the federal government were to require such investigations, this would complicate thousands or perhaps millions of transactions. It would, however, produce relatively little incremental benefit. It might stop an occasional transaction with the rare disreputable foreign investor who otherwise slipped through the net, and who ordinary private players were able to “catch” through their investigative or verification efforts. But those cases would represent needles in a haystack.

If “bad guys” hiding behind “shell companies” are in fact a serious problem in residential real estate, then we should try to identify a solution that imposes as few new burdens as possible, and relies to the maximum extent possible on—and perhaps adjusts a bit—the very expensive mechanisms that already exist, i.e., monitoring by banks and the federal immigration system.

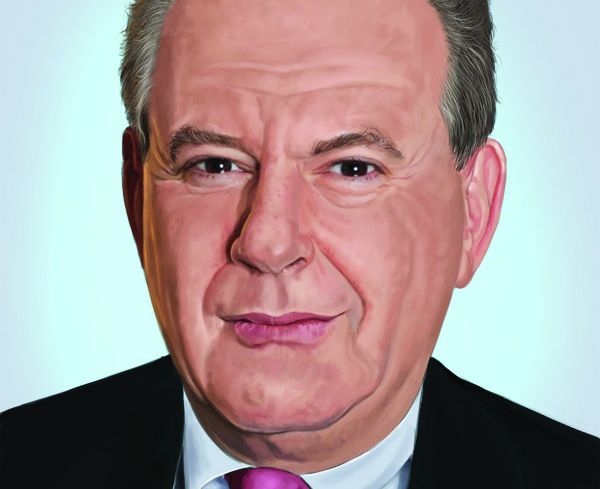

Joshua Stein is the sole principal of Joshua Stein PLLC. The views expressed here are his own. He can be reached at joshua@joshuastein.com.