Daniel Libeskind Memorializes, Moves Forward

By Tobias Salinger September 24, 2014 10:00 am

reprints

World Trade Center master planner Daniel Libeskind’s office library contains nearly a dozen bookcases filled with books about philosophy, religious studies, history, travel, literature, art, architecture, design and other fields and genres. And when Commercial Observer visited Studio Daniel Libeskind three blocks south of the trade center site, he described the necessity in his work of the same four components Herman Melville wishes for in Moby Dick: time, strength, cash and patience.

He had invoked the same line a few days days earlier during a trade center construction update event at 4 World Trade Center timed for the week of the 13th anniversary of the 9/11 attacks. The four necessities have helped rebuild the site where 2,753 New Yorkers lost their lives and fulfill the vision that guided the nation-sized group of stakeholders to the site’s current status, he told a room full of local and international media outlets and several of the interested parties themselves.

With construction proceeding at the site as 1 World Trade Center opens, 3 World Trade Center rises upward and the transportation hub lurches toward completion, the architect, planner and designer that the lower Manhattan Development Corporation selected as the master planner for the site in February 2003 expressed respect and gratitude to the many other actors who had shaped the 16-acre site. The Polish-American immigrant who arrived to New York City in a boat is also building all over the world as he relishes what would seem to be the most difficult aspect of his work.

“You have to love working with the clients that you work with,” said Mr. Libeskind, a 68-year-old father of three whose wife, Nina, started the architecture studio with him in 1990. “I’ve always thought that a project is not about the star architect. It’s about working with all those people creatively. I think, from the very beginning, architecture is a social art.”

But Mr. Libeskind’s personal history also shapes his work, he said. He moved from the Polish city of Łódź to New York as a 13-year-old with his parents, Holocaust survivors who settled in the Bronx not far from the Bronx High School of Science, which he attended. His mother, a garment worker, and his father, a printer, lived out the dream of a new life in America in a way that displays the triumphs and tribulations of living in the city, he says.

“It’s not an easy place to live,” Mr. Libeskind said. “My parents worked hard and everyone works hard. It’s a city where you can develop yourself.”

The Cooper Union graduate has addressed the tragedy that wiped out so many of his parents’ generation through projects like the design competition he won to build the zigzagging Jewish Museum of Berlin prior to the trade center design contest. Since the trade center, he’s also installed a five-story concrete and steel wedge renovation to open up one side of the formerly symmetrical Dresden Museum of Military History to light and a new era, completed the free-standing plaza and sculpture at the Ohio Statehouse Holocaust Memorial in Columbus and will finish the Ottawa National Holocaust Monument in the Canadian capital next year.

But Mr. Libeskind also takes on projects in other locales and fields, such as the stainless steel Spirit House Chairs that grace the lobby of the Park Hyatt hotel at One57 by Central Park. Condo buyers will presently be moving into another soon-to-be-completed building design by Mr. Libeskind at the L Tower, a 57-story, 600-unit structure next to Toronto’s Sony Centre for the Performing Arts. The arc-like Zhang ZhiDong and Modern Industrial Museum in Wuhan, China, a building in honor of a 19th century government official who led modernization efforts there, will be China’s first privately funded museum when it’s complete, Mr. Libeskind said. And the twisting red tiles of Mr. Libeskind’s thee-floor scheme for the Vanke Pavillion will stand out at the Milan Expo next year in a city where new buildings don’t represent the norm, he says.

|

“In the end, this site is proof of New York’s will. And we are so proud that will is proving as indomitable today as it has for 350 years.” |

“Very seldom in a historic city like Milan can you get land in the central part of town,” Mr. Libeskind said of the city where, along with Zurich, his firm keeps offices in addition to the New York headquarters. “It’s a whole new neighborhood picking up the historic scale of Milan.”

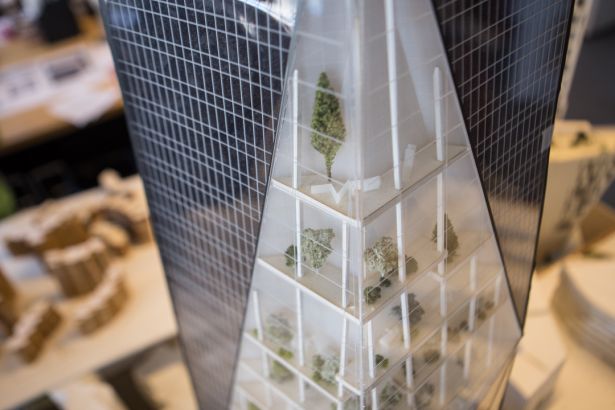

Yet, far closer to him and his wife’s home in Lower Manhattan, Mr. Libeskind continues to view the trade center site he designed taking shape, hailing its progress and evolution while observers question whether it aligns with the plan or raise critiques about the memorial or the rebuilding process. From the office adorned with an array of design tools, renderings and building models, the infectiously enthusiastic visionary will continue to stand front and center at each milestone or complex negotiation at the project whose twists and turns have never made him regret winning the design contest.

“I grew up in the Bronx—nothing is easy in New York,” Mr. Libeskind said. “If you understand that, you understand you don’t just do some renderings and retire or move on to something else.”

Mr. Libeskind looked on at 4 World Trade Center two weeks ago as officials from trade center leaseholder Silverstein Properties, site owner the Port Authority of New York & New Jersey and the state legislature drew attention to new leases at the now 58-percent-full 1 World Trade Center, the financing agreement Silverstein worked out with the Port Authority to resume building at the stalled 3 World Trade Center plot and construction they say is back on track at the subway and commuter train transportation hub and mall, despite a ballooning budget now approaching $4 billion. Everyone involved with the center should feel proud despite how long it’s taken to see the memorial, the museum and the rising landmarks coming into shape in the footprint designed by Mr. Libeskind, said Larry Silverstein, the chairman of Silverstein Properties.

“His vision knitted together a fitting and moving tribute to those that lost their lives, a bustling street-level experience with grand open spaces, a train station, as well as new office buildings and stores,” Mr. Silverstein said. “In short, he created a plan that achieved everyone’s goal—to create a better version of New York.”

Mr. Silverstein and other officials rattled off statistics showing, they said, that the site is a success. Companies, many of them from the technology, advertising, media and information sectors, have signed for 5 million square feet of space at the rebuilt trade center and over 511 firms have relocated to Lower Manhattan commercial spaces like the World Trade Center, Brookfield Place and the Financial District since 2005, officials said. Additionally, over 15 million people have visited the 9/11 Memorial since its opening in September 2011 and over 1 million have taken in the museum since it opened in May, according to the National September 11 Memorial and Museum.

The turnaround from the dark days after the terrorist strikes embodies the resilience of the city, said first deputy mayor and former Port Authority executive director Anthony Shorris.

“In the end, this site is proof of New York’s will,” said Mr. Shorris. “And we are so proud that will is proving as indomitable today as it has for 350 years.”

Yet others question whether the buildings that Mr. Libeskind notes do look aesthetically different from his competition-winning renderings or if the restricted, sensitive nature of the public space at the site conform to his rebuilding plan. He didn’t directly design the memorial, the museum, the train station or any of the buildings themselves. And visitors to the eight acres of public space on the site face prohibitions on sports and recreation activities, sleeping, commercial activities, loitering, leafleting, demonstrating, lighting candles and “engaging in expressive activity that has the effect, intent or propensity to draw a crowd of onlookers” without a permit, according to the memorial’s website.

But without calling for any specific changes to such policies, Mr. Libeskind predicted that the site will continue to evolve and noted that features like the centrality of the memorial to the site, the 1,776-foot tower, and the eventual reconnecting of the complex to the surrounding street grid fall right in line with his original vision. Calling the trade center’s construction “very much according to the master plan,” he compared his role in the process to that of a composer.

“When you are a composer, you write a score,” said Mr. Libeskind. “The composer will not be on stage. But everything that goes on there will be due to a very specific arrangement, and it will have to be interpreted.”