In today’s commercial real estate finance market, borrowers can often choose from a plethora of lenders, offering reasonable loan proceeds at better-than-reasonable pricing. Each lender presents itself as cooperative, accommodating, practical and quick.

Against that backdrop, borrowers face tremendous temptation to play the field—go into the market and find the best possible lender for each deal—save a few basis points here, avoid an escrow nuisance there and get a more favorable prepayment penalty somewhere else.

That strategy can mean that each loan transaction involves a new relationship. Each time, the borrower and its counsel need to get to know a new counterparty and how it does business. No matter how accommodating a lender seems at the outset, it is still a lender, and it will still have its own sensitivities and expectations about how to do business. The first time a borrower does business with that lender, the process will often not go perfectly because of those surprises.

As part of getting to know the new lender, a borrower will also need to get to know that lender’s loan documents. Although most loan documents say mostly the same things, they often say them in different ways, and every lender has its own surprises. So borrower’s counsel needs to carefully review and negotiate a whole new set of documents every time the borrower goes to a different lender. And at the moment of closing, each lender will often have its own specific procedures and requirements that need to be satisfied before the lender actually wires money.

If a borrower consistently jumps from lender to lender, this may have some appeal to it for the reasons suggested above. In my experience, though, borrowers often don’t attach enough value to the benefits of sticking with, say, two or three lenders and going back to those lenders again and again when possible. That seems particularly easy to do if a borrower closes a particular type of transaction, with a similar investment structure and investors, repeatedly.

Once a borrower and its counsel get to know a lender and its counsel, the negotiation and closing process can become much more streamlined and efficient. Instead of needing to fully review and negotiate a new set of loan documents each time, counsel can focus on differences between this deal and the last one or the agreed template documents. This makes it easier to focus on the mechanics of getting to closing, which will go better and faster because the same parties have done it before. Consistency in lender relationships might also save money and achieve quicker closings, exactly what most borrowers want.

If the borrower can reuse basically the same documents that the parties negotiated for the last transaction, that avoids the need to fully rethink everything in the documents—assuming, of course, that for a previous transaction the borrower and its counsel gave the documents a thorough reading. Among other things, that reduces the likelihood of some expensive “gotcha” clause in the documents that counsel might have missed because of the time pressure to close the current transaction.

Consistent use of the same small group of lenders makes the most sense for acquisition transactions, where the borrower must close two transactions simultaneously and might find itself stuck between an unknown and potentially difficult seller and the lender. If the lender is a known quantity not requiring inordinate time and attention, it can speed along the transaction, reduce risk of problems and help iron out whatever problems do arise.

After the closing, if a borrower maintains a small stable of lenders, this makes it easier for the borrower to maintain relationships and have someone to talk to if problems ever arise. If the borrower systematically cares for and feeds those lenders, when the borrower needs something, it will probably be easier than if the borrower first needs to figure out who to call, because the borrower doesn’t really know much about the lender or who has responsibility for this particular loan.

As with any suggestion, there are always plenty of good reasons to reject the suggestions in this column. The borrower’s deals may vary so much that each one will appeal to a different lender. Diversity of lenders may protect the borrower in a financial crisis or market collapse. A borrower may be more willing to play hardball with a lender with whom the borrower doesn’t have a relationship. And it’s always nice to save a little bit of interest by always going to the lowest-cost lender every time.

In weighing the various options, borrowers ought to give more weight than they often do to the benefits of sticking with a small team of horses and riding them again and again. It often works out better that way.

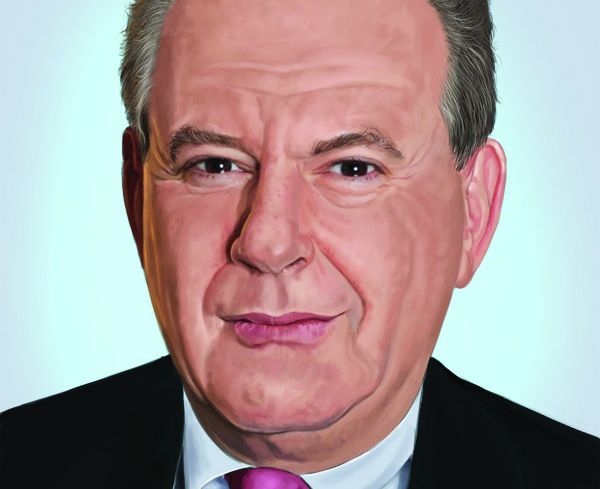

Joshua Stein is the sole principal of Joshua Stein PLLC. The views expressed here are his own. He can be reached at joshua@joshuastein.com.