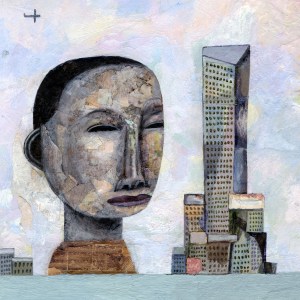

On Top of the World, Icarus Lives (On the 75th Floor)

By The Editors October 8, 2013 6:00 am

reprintsImagine that you’re a billionaire and can afford to buy a spectacular apartment at the very top of an 80-story building, with a panoramic view to die for. For some people, the $60 million admission fee is not an obstacle as much as an attraction. A Manhattan penthouse will only go up in value, they say.

For just a little more, you can buy some- thing truly unique—an octagonal penthouse at the top of the CitySpire building. The apartment occupies the 73rd, 74th and 75th floors with 360-degree wraparound terraces. It was recently listed for $100 million. Another penthouse, 90 floors above Manhattan, has a 30-foot water wall and reflecting pool over- looking the United Nations headquarters.

Interested?

Yet not every billionaire is positioning for one of a slew of new apartments that are coming on the market. In fact, some, like Warren Buffet, prefer to live modestly. What motivates a man—or woman—to be at the very top?

In Greek mythology, Daedelus is the crafty inventor responsible for the Cretan labyrinth that imprisoned the Minotaur. But Daedelus is also famous for something else: two pairs of wings fashioned from feathers and wax. One pair was for himself and one for his son, Icarus. As they set out on their first flight, he cautioned Icarus to follow in his path and especially not to fly too close to sun. But Icarus, in the exuberance of youth and his new power, did just that. The sun melted the wax, and Icarus fell into the sea.

Icarus was dazzled by having what no man before him had ever had—save his father. One can imagine a multibillionaire being similarly dazzled by the world’s treasures available to him and perhaps equally desirous of going at least a little higher than his father (or business competitors).

“I’m on top of the world,” someone says, and we recognize this as a metaphor. But some people want to actually be there, if not quite literally or for long (the top of Mt. Everest isn’t the best site for luxury entertaining) but with enough height to give the symbolism spine.

And, yes, it can go back to childhood. Boys like to compete, and who didn’t want to be king of the hill—or hoped to show them all one day? Aiming for the top is downright archetypal.

The medieval duke with a castle on a hill was in a better position to repel enemies. God, as everyone knows, looks down on us from above. Yet the Manhattan penthouse is not in any real way a safer or more powerful place. If anything, it’s more dangerous, as we know from the visit of Hurricane Sandy; you don’t want to be 80 stories up when the electricity goes out.

But it’s fair to say the world’s billionaires are not worried about most of nature’s threats. They live in an unreal world with more money than they can ever spend. What those electronic billions are good for is a way of keeping score and, perhaps more unconsciously, a way of convincing them- selves that they are protected from the one natural threat none of us avoid—death.

Man is the only animal for whom his own existence is a problem which he has to solve. —Erich Fromm

Forty years ago, Ernest Becker wrote in The Denial of Death about the human predicament of being aware from child- hood that someday we will die. Is there a creature other than man that’s capable of brooding over the sting of it all ending?

Humanity deals with this knowledge through denial, what Becker called “immortality projects.” Religion, philosophy, family, art and hedonism are all examples of these projects. In the afterlife, you are rewarded for your good deeds. If you com- pose a wonderful piece of music or paint a masterpiece, your fame will live after you. Your children and grandchildren carry on your name. Or, as the poet George Herbert wrote, “Living well is the best revenge.”

Still, there’s a difference between living well and living at the very top of one of the world’s tallest buildings. It says that I’m better than you—bigger, stronger and more powerful. I’m not simply one man in a world of billions, aging every day, head- ed for oblivion. I’m the king of the hill.

The people who buy these unimaginably luxurious apartments know, of course, that they will die. They also know that power and wealth can’t really make up for child- hood deficits—the parents who were criti- cal or indifferent, the schoolhouse bullies. But if the perks of wealth can’t erase the past or change the inevitable future, they do a brilliant job of masking both. That stunning view of Manhattan, all lit up at night, can be very distracting.

Of course, some people are just looking for some peace and quiet.

And a nice $60 million penthouse does the trick.

Mark R. Banschick, M.D., is a psychiatrist with training from Georgetown University Medical Center and New York Presbyterian Hospital/ Weill Medical Center. He is the author of The Intelligent Divorce book series and contributes regularly to Psychology Today. Dr. Banschick is in private practice in Katonah, N.Y.