Hostel Takeover: The Return of the Backpacker Crash Pad

By Billy Gray June 25, 2013 9:00 am

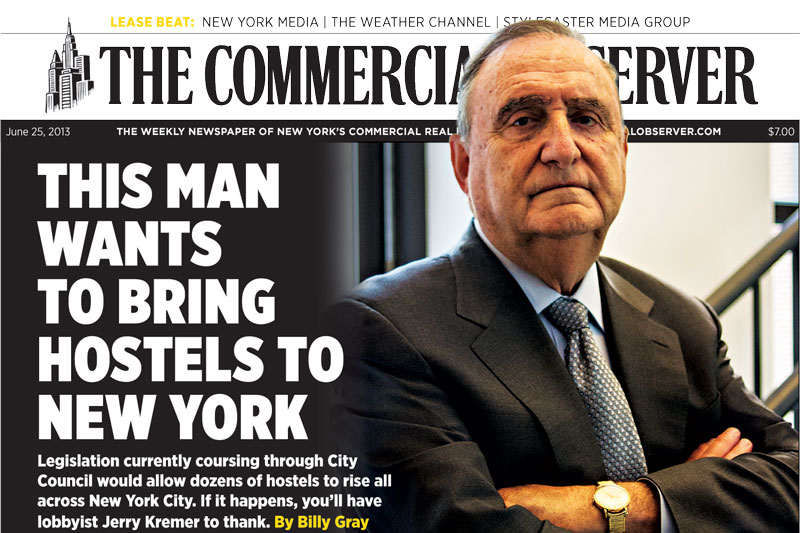

reprints Jerry Kremer wouldn’t back down on the matter of bunk beds.

Jerry Kremer wouldn’t back down on the matter of bunk beds.

Mr. Kremer, a former New York State assemblyman and founder of Empire Government Strategies, is lobbying for the passage of legislation that would permit the licensing of hostels in the city and encourage their growth here. New York has never really embraced the hostel model, which until very recently conjured for the average American images of dingy, druggy European backpacker crash pads.

But local legislation in 2010, bill S6873/A10008, which sought to clamp down on SROs and other illegal hotels, also dented the smattering of hostels that had thrived in the city. Mr. Kremer and other advocates of the corrective bill, 1014-2013—Mayor Bloomberg and Speaker Christine Quinn among them—insist that hostels were collateral damage.

“They were not [the intended target],” Mr. Kremer said in an interview. “They were the drive-by shooting, the innocent victim. “

And while hostels have historically operated on the margins of New York’s hospitality industry, their presence tiny compared with the hostel footprint in Berlin, Barcelona and even exorbitantly expensive London, some studies estimate that mass closings following the 2010 bill are costing the city $150 million and nearly 200,000 tourists a year.

Those numbers may seem paltry in the grand scheme of New York’s tourism industry—a record 52 million people visited the city last year, generating about $55 billion. Yet Mr. Kremer and other advocates of the industry argue that the city is losing out on a generation of young, budget- and style-conscious tourists who increasingly steer clear of Manhattan and the outer boroughs in favor not only of European and Asian capitals, but also of Philadelphia, San Francisco and Miami.

“The city took a real blow,” Mr. Kremer said. “Places like Philly and Washington saw a dramatic increase in young travelers and hostel occupancy rates. They siphoned it away from New York and were indirect beneficiaries of that 2010 legislation. And the economic impact was devastating.”

A 2011 study by the Dublin-based online hostel booker Web Reservations International reported that between 2008 and June 2011, the number of active hostels in New York plummeted to 25 from 85. There were just over 100 licensed hostels in operation in London and 90 in Berlin, a city half New York’s size with one-fifth as many annual visitors.

Meanwhile, between 2010 and 2011, the study showed, 47 hostels closed in New York while five new ones sprung up in Las Vegas.

The new local law would establish an independent office within the business integrity commission for licensed hostels, defined as “class B multiple dwellings providing food, lodging and other services to travelers … accommodation in which more than 70 percent of the dwellings are hostel units.” A hostel unit sleeps between four and eight guests. Stays in excess of 29 days would not be permitted, which helps distinguish hostels from SROs and illegal hotels. When talks about prohibiting bunk beds in the definition came up, Mr. Kremer put his foot down. “You can’t have a hostel without bunk beds,” he said. Instead, per the new bill, they won’t be able to be placed within three feet of each other. He said the European hostel groups he’s spoken to “can live with that.”

Mr. Kremer has wanted to correct the wrongs of the 2010 bill since shortly after its passage, when HostelWorld, among the world’s biggest placers of hostel guests, hired him to consult and lobby on behalf of the industry. He has a vested interest in codifying hostels in New York, but Mr. Kremer also believes that the city is on the verge of missing out on a major spike in the popularity of hostels among American travelers.

Indeed, a new breed of hostel has recently transfixed travel desk editors and 30-and-under travelers of a certain hipster bent. The Freehand, in Miami, may be the most prominent example on these shores. The “communal-living place for unmoneyed cool people,” in Curbed’s words, opened just north of South Beach’s neon nightlife bustle in late 2012, just in time for the chic hordes in town for Art Basel.

New York’s Sydell Group developed The Freehand, which the on-trend architecture firm Roman and Williams designed. It was a logical progression from the Sydell-owned Ace Hotels in New York and Palm Springs, funky boutiques squarely aimed at the fixed-gear-bike set. There were bunk beds and shared bathrooms, yes, but also a nu-cocktail bar (with garnishes supposedly plucked from the courtyard) and a hopping late-night scene centered around a pool.

In May, Sydell announced plans for a New York Freehand in Williamsburg, natch, where it had bought three parcels on Wythe Avenue for $10 million late last year. In a clear indication of the money riding on the newfangled hostel paradigm, the billionaire Ron Burkle’s Yucaipa Companies is an investor in Sydell and the Freehand line. There are currently plans for 10 Freehands across the country.

Andrew Zobler, the founder and chief executive of the Sydell Group, agrees with Mr. Kremer when it comes to the neglected hostel market in New York.

“The city is very underserved by affordable options for the youth and budget traveler, and this is not good for the culture of the city or for the economy,” Mr. Zobler said in an email. “Youth travel is a very large business and is a very rapidly growing segment of the travel market. It is important for the city to serve as a good host for this traveler, and we are not doing a great job at it.”

Although it seems like The Freehand and the Ace may have an overlapping client base, Mr. Zobler, in branding-savvy terms, downplayed any sense of competition between the companies.

“We think Freehand is complementary to other lifestyle products,” he said. “The idea is to provide a quality experience on par with lifestyle hotels but at less expensive entry pricing and to offer a more communal atmosphere than at a hotel.”

Mr. Kremer went a step further than that when he argued that a healthy hostel infrastructure would actually benefit the boutique and mainstream hotel sectors.

“My pitch to the hotel industry is, ‘Look, today’s hostel users are tomorrow’s guests,’” he said. “These people who are introduced to New York through hostels are coming back in a few years when they have jobs and are going to the Hilton. It’s not a competition. Hostels are entry-level, or gateway, lodgings.”

Besides, it’s not like The Freehand would rub up against The Carlyle. Williamsburg, Long Island City and Sunnyside are considered ideal launching pads for the city’s potential hostel base. “No one wanted [these hostels] in residential areas,” Mr. Kremer said. “They’re only [proposed for] commercial areas. And although I’d like to convince the city of this, I don’t think on the first round they’ll do manufacturing areas.”

While there’s been limited backlash from the hotel industry and its lobbyists, the hostel bill, like so many others, hasn’t exactly sailed through the red tape of City Hall. The holdup is especially surprising given Mayor Bloomberg’s endorsement of the proposal.

“Even though we’ve become the No. 1 tourism destination in the country, we still have unfinished business,” Mayor Bloomberg said in February during his final State of the City address. “Right now, we’re missing out on an important piece of the market: the young people who have an itch to get out and see the world on modest budgets. Hotels in our city can be out of their price range. So, working with Speaker Quinn and the City Council, we’ll pass legislation to make New York a more youth-friendly tourism destination by legalizing the for-profit youth hostels that are so common in much of Europe.”

What’s the delay in passing the hostel law? There may be a lingering conflation of hostels with the seedy SROs and illegal, multiple-dwelling lodgings that the 2010 bill aimed to shut down.

Questions also hover around City Councilmember Erik Martin Dilan, the chair of the housing and buildings committee and a sponsor of the hostel bill. In 2011, The New York Observer reported on the controversy surrounding Councilman Dilan’s then-chief of staff Rafael Espinal and his acceptance of contributions during his State Assembly campaign from “accused slumlord and shady hotel mogul” Jay Wartski, who was accused of illegally removing tenants in order to create space for illegal hotel guests.

Mr. Espinal emerged from the controversy unscathed to become the New York State assemblyman representing the 54th District, which comprises Bushwick, Bed-Stuy, Cypress Hills and East New York.

But memories of Councilman Dilan’s ties to Mr. Wartski, who in 2009 donated $2,000 to the councilman’s campaign, drew suspicion from some sources about his dedication to a bill that would aid licensed hostels and potentially cut into the illegal hotel black market.

As of Monday, Councilman Dilan had not responded to repeated phone and email requests for comment.

Regardless of the reasons behind the logjam, Mr. Kremer said of the legislation that “if it’s not done this year, we go back to scratch.” Noting that it was “legacy time” for Mayor Bloomberg, he said that the bill is “on third base and inching toward home plate.”

Kimberly Spell, the chief communications officer of NYC & Company, described the hostel bill as the city’s official marketing and tourism organization’s “only legislative ask,” adding that she, like Mr. Kremer, anxiously awaits it moving to a committee hearing.

Ms. Spell also pointed out that the bill would not only attract young travelers, but also elderly tourists of modest means. She said there’s clear economic and cultural potential between these “two vulnerable populations on the same end of the income spectrum.”

With projects like The Freehand Williamsburg already announced and Mayor Bloomberg’s tourism-boosting tenure drawing to a close, action on the hostel law should occur by the end of this year. In the meantime, young, savvy travelers priced out of most local hotels will continue to clog options like The Ace and Jane Hotel, or simply take their wallets, however thin, elsewhere.

What’s clear is that hostels (of a certain stripe) are suddenly in vogue as they begin to resemble boutiques. And that’s happening just as the biggest hotel chains start to resemble hostels: earlier this month, the New York Hilton Midtown announced that it would discontinue room service.

Should the bill pass, Mr. Kremer thinks that “maybe a dozen hostels” will open within a year. Beyond that, the future of bargain-basement lodgings should only soar.

“The question is,” Mr. Kremer said, “will the big boys jump in? If they do, then the sky’s the limit.”