CIM City: Mystery California Land-Eater Devours New York City Next

By Laura Kusisto May 10, 2011 11:44 pm

reprints Few know the true genesis of CIM, but the legend goes like this: In 1986 two Israeli soldiers, who worked on a kibbutz together, came to California on vacation and decided to stay. They started a small landscaping business and bought a couple of cheap apartment buildings, when one day they struck up a conversation about grass or some such with Richard Ressler, an alum of ’80s junk-bond yard Drexel Burnham.

Few know the true genesis of CIM, but the legend goes like this: In 1986 two Israeli soldiers, who worked on a kibbutz together, came to California on vacation and decided to stay. They started a small landscaping business and bought a couple of cheap apartment buildings, when one day they struck up a conversation about grass or some such with Richard Ressler, an alum of ’80s junk-bond yard Drexel Burnham.

Using that same knack for unorthodox investments, the trio started the CIM Group in 1994, and its investment funds have spread across the country, buying up thousands of apartment units, as well as malls, hotels and theaters in second-tier markets such as L.A., Las Vegas and Dallas.

“They are a vulture,” said Scott Adams, chief urban redevelopment officer for Las Vegas, who has worked with CIM. “I mean that in a good way.” With the country’s glitziest strips littered with victims of the worst real estate bust in at least a decade, we need scavengers to feed off the wounded.

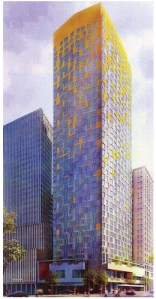

Now the vulture has landed here too. CIM bought Harry Macklowe’s distressed Drake Hotel site for $305 million in cash last January. More recently, it’s bought Sapir’s William Beaver House and a stake in 11 Madison, and partnered with the troubled developer on the Trump SoHo.

What happens in Vegas, a kingdom of slapdash hotels and casinos where by Mr. Adams’ admission “almost anybody could be a developer,” once stayed in Vegas. But New York is now littered with ailing condo and hotel projects once owned by some of the city’s most prominent real estate figures.

“They came in like a white knight,” said Dan Fasulo, managing director of research at Real Capital Analytics. Well, sort of. “They play behind the scenes,” he added. “They are obviously pursuing a strategy not to compete with the big boys that are getting involved in controlled auctions.”

A COUPLE OF days after The Observer began working on this story, before we had called CIM, they called us. “I hear you’re working hard on a profile of CIM,” said a company spokesman. He also knew our deadline and word count, and quietly kept tabs on us throughout, but the company, of course, refused to comment. So we went to CIM’s offices on the 41st floor of a Madison Avenue tower, filled mostly with dentists and physio’s offices. Half-a-dozen windowed offices rim the perimeter, piled high with documents and used coffee cups. But early on a Tuesday morning, the office was quiet, its only inhabitants a receptionist and a silver-haired man in a pale blue shirt and slacks pacing back and forth with a stack of papers in hand. They glanced at The Observer perching in the waiting room, but said nothing.

As CIM became more active in New York, they brought in Justin Rimel and several others from Los Angeles, say people who have worked with the company. A graduate of Berkeley’s business program and a former member of Ernst & Young’s real estate group, Mr. Rimel is the closest thing to a local face for CIM, but even he remains mostly hidden.

While in New York, CIM is still a shadowy outsider, they’ve long ago learned to navigate L.A.’s narrow channels of power. “L.A. is a tight little town, where there are relatively few power players,” said Ron Kaye, the former editor of the Los Angeles Daily News. “The influence just spreads through a very narrow power system … It’s so light and dark.” To wit, Mr. Ressler’s sister is married to fellow Drexel alum Leon Black, who commands Apollo Management; he owns a stake in the Milwaukee brewers thanks to his college roommate, Mark Attanasio; his brother, Tony Ressler, is the head of Ares Capital, which manages billions of dollars of capital.

CIM has also received substantial investment from different California pension plans and millions of dollars from L.A.’s development agency. “Most of what they’ve done is in L.A. or in smaller communities,” said Mr. Kaye provocatively, “where they can just go in, throw around a lot of money and get what they wanted.”

But CIM’s success lies much more in its willingness to take over a sites so pockmarked with problems few will touch them, and transform not only an individual property but the neighborhood around it. They’re credited, for example, with reviving the Hollywood & Highland, a complex in which the Oscars are held-which until they took over, was such a warren of unreachable and over-priced stores that not even tourists would shop there.

Without the flash of other local developers, such as Rick Caruso, the skilled turnaround artists have become the largest commercial landlord in Hollywood in not much more than a decade. New York could be their next conquest.