City Officials, SL Green Respond to Grand Central Landlord

By Tobias Salinger July 23, 2014 6:51 pm

reprints

A week after a contentious Department of City Planning hearing on the Vanderbilt Corridor proposal to rezone five blocks in Midtown East, City Planning officials and attorneys for SL Green (SLG) Realty Corp. doubled down on their view that the proposal won’t block Grand Central Terminal landlord Argent Ventures from selling the historic property’s unused air rights.

With Argent and preservation advocates raising tough questions about whether a go-ahead to build the One Vanderbilt office tower adjacent to Grand Central without buying any transferable development rights from Argent would hinder needed aid to a city landmark, SL Green lawyers and city officials responded with a full-throated defense of the plan.

“We maintain that we have not ended or taken away their ability to sell air rights,” said Anita Laremont, the city agency’s general counsel. “To the contrary, we’ve enhanced it.”

The plan that offers owners the option of buying transferable development rights or creating public improvements allows for larger purchases of air rights than the existing zoning for the area, said Ms. Laremont, who contended that Argent’s claims that the city violated its property rights mean that any new landmarks designations in the future would infringe on private ownership.

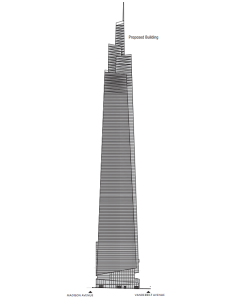

And SL Green’s commitment to completing $200 million in public improvements before getting any certificates of occupancy at the 67-story, 1.8-million-square foot skyscraper establishes a more stringent standard than the requirements in last year’s failed Midtown East rezoning proposal, said Stephen Lefkowitz of Fried, Frank, Harris, Shriver & Jacobson.

“This is not simply dollars being paid either to the city or Grand Central Terminal,” Mr. Lefkowitz said. “This is work the developer will have to do. This is a different obligation than writing a check. We’re taking the risk that this could turn out to cost not $200 million, but a lot more.”

But Argent’s attorney, Paul Selver of Kramer Levin Naftalis & Frankel, dismissed the developer’s plans for the public improvements as a minimal price for their building bonuses and asserted that the proposal prevents his client from selling 530,000 square feet of air rights in written testimony he submitted to the agency last week. He called the remarks by the city officials and SL Green lawyers “a straw man argument” and repeated his claim that the city had maneuvered around Argent by providing the alternate option for higher building heights.

“This means that the city will always be in a position to offer additional floor area at a lower cost to the developer—and that is exactly what they have done at One Vanderbilt,” Mr. Selver wrote in an email statement. “Moreover, the process for setting this cost is a big step backward in transparency because, rather than fix a price per square foot and a process for adjusting it through zoning text, the manner in which the transit improvements are being established and the methodology for their valuation is shrouded in mystery.”

The Vanderbilt Corridor proposal has also raised red flags with preservation advocacy groups, who expressed concern that other landmarks could miss out on a key source of funding, with landmarks south of Central Park in Manhattan currently sitting on over 33 million square feet of unused rights, according to a recent report by the NYU Furman Center. The proposal—which hasn’t even started the Uniform Land Use Procedure yet—could set a bad precedent if it allows developers to build higher without buying the right to do so from adjacent historic sites, said Peg Breen, the president of the New York Landmarks Conservancy.

“Each of these transactions provides significant amounts of money for the landmarks,” Ms. Breen said. “It does provide benefits that particularly religious buildings would have a hard time getting any other way.”

But the proposal might also offer the city a path to further its development goals for particular neighborhoods while paying for public improvements like the 4,500-square-foot public space SL Green has planned for the site, said Ross F. Moskowitz, a real estate partner at Stroock & Stroock & Lavan who specializes in land use matters.

“I think legitimate concerns were raised on the impact of the Grand Central Terminal transferable development rights,” Mr. Moskowitz, who isn’t representing any of the parties, said in a prepared statement. “The De Blasio administration has recognized this, and the new proposal allows a purchaser of transferable development rights to utilize a cost-benefit analysis in deciding which path to choose. Neither option should be superior, and this proposal allows for additional options to encourage tools to foster development.”