New York’s Housing Crisis Isn’t Keeping Albany Up at Night This Year

Little in the way of new policy as stakeholders, including developers, continue to call for change

By Aaron Short January 14, 2025 2:08 pm

reprints

For the past three years, New York Gov. Kathy Hochul made housing affordability her top legislative priority. This year, it’s more of an also-ran behind other initiatives.

Last month, Hochul promised to draft new immigration proposals to target undocumented immigrants who committed crimes after indicating she was open to cooperating with the incoming Trump administration on the issue. On Jan. 3, she suggested she would change state law to make it easier to involuntarily commit people with mental illnesses to hospitals as a way to address chronic homelessness.

And she will have to negotiate with the legislature over billions of dollars in school aid, plus how to fund the Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s capital plan after legislative leaders rejected the agency’s $68 billion-plus proposal in December.

As for housing policy, the proposals are more modest. At her Tuesday State of the State address, Hochul declared her intention to tackle the state’s high cost of living and proposed sending “inflation refund” checks of $300 to $500 to 8.6 million New Yorkers.

She also pitched a plan to spend $50 million to spur the construction of more affordable starter homes and another $50 million to aid in down payments. Hochul, too, wants to curb the buying power of institutional investors such as private equity funds when it comes to single-family homes that they can in turn rent out.

All of this pales in comparison to Hochul’s past housing proposals. That visible shift in priorities is fueling pessimism in commercial real estate about the possibility of fresh residential development incentives coming out of the new legislative session. There’s precedent for disappointment.

“People are somewhere between extremely and very dissatisfied with the last session,” one developer said. “It’s always a hurdle when difficult political decisions need to be made but people have fatigue from last session. It would be surprising if really substantive issues got opened up again.”

That reluctance is understandable, since the governor has been burned each year she has tried to incentivize developing more housing.

In early 2022, Hochul wanted to allow basement and garden apartments in communities zoned for single-family housing and to increase residential density in parts of New York City. But she nixed the apartments idea after Long Island lawmakers opposed any move that would override local zoning laws.

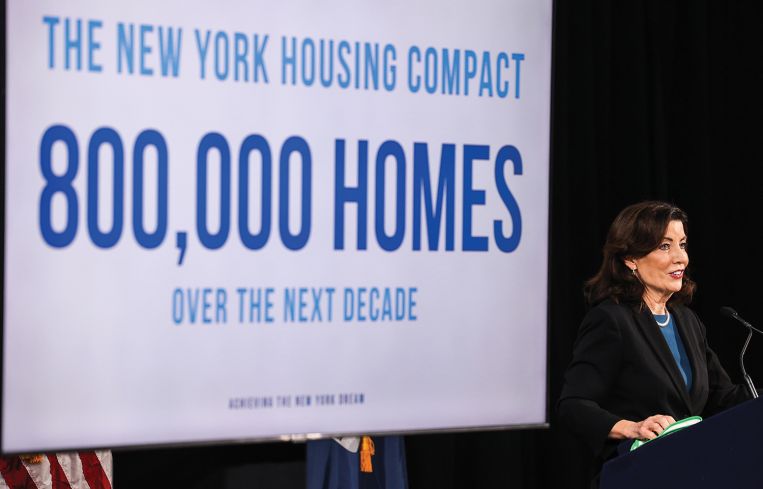

The following January, Hochul unveiled an ambitious program that would have mandated the construction of new homes in every locality and result in 800,000 new units across the state over the next decade. But suburban lawmakers and their constituents revolted, and Hochul scrapped the plan in April 2023 after contentious negotiations prevented the state budget from passing on time.

A year ago, she dropped the construction mandates, and instead proposed a tax incentive for developers to build more market-rate residential projects. Legislators finally went along with that idea and added labor standards and eviction protections for tenants, which passed in 2024’s $237 billion budget.

But the demand for new housing has continued to grow. New York City’s apartment vacancy rate reached a historic low of 1.4 percent, according to a city housing and vacancy survey released in February 2024. As of 2022, New York needed 226,000 homes to alleviate its housing crunch and another 395,000 units to meet projected demand by 2032, according to a Regional Plan Association analysis.

The lack of available apartments is already having an effect by forcing young families to look elsewhere for less expensive places to live. More than one-third of New York state residents who moved away said housing costs were the primary reason, according to Census data released in 2024.

The housing crisis remains top of mind for most New Yorkers. When a Siena College poll at the end of last year asked what Albany should prioritize in 2025, 43 percent of voters said cost of living and 19 percent said housing. The same poll found that Hochul’s favorability rating remained underwater, and that 57 percent of voters would prefer to elect someone else.

Political consultant Hank Sheinkopf said the legislature and the governor share the blame for housing becoming unaffordable for most New Yorkers.

“Developers take the risk to build properties, but they’re no longer being rewarded, and that’s the legislature’s problem. How are they going to ease that risk? They’re likely not going to do anything about it,” Sheinkopf said. “Everybody wants the solution, but they’re not telling you what the solution is and they’re not prepared to pay the price.”

Even though there likely won’t be a comprehensive housing package this year, lawmakers are still sponsoring bills that could mitigate the costs of renting or owning a home.

One proposal that could reach the governor’s desk is a state-funded voucher program that would provide rental assistance to homeless and low-income families in danger of losing their apartments. Legislators proposed the housing access voucher bill last year, which gained support from a wide swath of tenant and legal advocacy groups and owner trade associations, including the Real Estate Board of New York.

Hochul ultimately refused to commit $250 million for the program in the state budget. But a task force she appointed to examine child poverty found that a housing access voucher program could reduce poverty by 16 percent across the state, according to its December report.

In addition, legislators will ask to expand a pilot program for social services organizations to prevent evictions when tenants are unable to pay rent. The state reserved $10 million last year, but Senate Housing Committee Chairman Brian Kavanagh of Lower Manhattan believes the cost of evictions resulting from unpaid rent is more likely between $50 million and $80 million.

“It’s a small price to pay to keep people in their homes across the state,” he said. “It’s distributed proportionate to the eviction and rent burden rates in each county.”

Assembly Housing Committee Chair Linda Rosenthal, who represents Manhattan’s Upper West Side, also wants to see more funding for public housing and nonprofit supportive housing organizations. She’s holding a hearing on the capital and operating needs of the state’s Mitchell-Lama program, which provides rental and cooperative housing to moderate-income families. But future state budget allocations for building upgrades could depend on whether the Trump administration slashes funding for federal housing programs, including those through the New York City Housing Authority and Section 8 programs.

“We see what happens when you don’t keep up maintenance,” Rosenthal said. “It would be a fair amount of money, but you either pay now or you pay later. And, if you pay later, it will be more expensive.”

Real estate leaders have their own wish list this year, although lawmakers could block some of those ideas.

Developers could be looking for adjustments to the 485x tax abatement that passed in last year’s budget. When the governor in late 2023 essentially extended the benefits of the 421a tax incentive that the legislature let expire, 18 projects restarted in Gowanus. But few new developments are moving forward under 485x, the measure designed to replace 421a.

One reason is that developers say construction costs for new projects are too high under 485x because of the prevailing wage rates they’re required to pay. Owners negotiated a tiered wage scale for Manhattan and parts of the outer boroughs with labor unions a year ago, but that hasn’t spurred new construction in the city and along the East River waterfront.

“The thing that will produce the most housing is the extension of the completion deadline of the old program,” said Jordan Barowitz, principal at Barowitz Advisory, which has commercial real estate clients. “It’s going to take awhile for people to take advantage of the new 485x and eclipse the number of units that extending the completion deadline will get.”

Landlords of rent-stabilized buildings want to rein in rising costs from operating the smaller buildings they already own. The New York Apartment Association, which represents property owners and managers of affordable multifamily buildings, is looking for relief from water and utility bills, property taxes, and ballooning property and liability insurance costs. The group also supports the proposed Housing Access Voucher Program, but wants to use a portion of a tenant’s voucher to renovate vacant rent-stabilized units to make them livable.

“We are open to whatever they deem viable and we can utilize it to bring down the expenses of operating housing. We’re being squeezed day in and day out,” said Kenny Burgos, CEO of the New York Apartment Association. “When it comes to rent-stabilized, they cannot pass costs down. You see the impact through the devaluation and defunding in the buildings.”

Property owners also may try to undo some of the rental protections that legislators approved in 2019, but that would not occur without a fight.

“Every year there are certain groups that say ‘Let’s chip away at protections,’ ” Rosenthal said. “In the midst of a major housing crisis with an increasing number of homeless people and so many tenants being rent burdened, why would we chip away at protections that keep people in their homes?”