California’s Inland Empire Draws More Retail and Residential Development

Higher housing costs on the coast are driving more residents to heavily industrial Riverside and San Bernardino counties

By Patrick Sisson December 3, 2024 4:00 pm

reprints

The old Sears department store in Riverside, Calif., about an hour due east of Los Angeles, has sat vacant and boarded up for the last five years. It was one of dozens of Sears locations nationwide to close since 2019. But, this October, plans commenced to demolish the empty retailer to make way for a $170 million mixed-use project containing nearly 400 apartments and townhomes, along with an Aldi grocery store, restaurants and other retail.

“This property represented an excellent opportunity to provide much-needed housing with an architectural style that the neighborhood can be proud of,” said Jamie Chapman, a development manager at Foulger Pratt, the developer behind the project. “Riverside is home to excellent universities, health care and employers which need housing for their employees.”

The city of Riverside sits in California’s vast Inland Empire, an arid stretch of former orange groves and horse farms in Southern California that has been transformed into one of the world’s densest collections of warehouses and logistics facilities. In commercial real estate circles, Riverside is known mainly for its proximity to that industrial development. More than 55 million square feet of industrial space came online in the Inland Empire since the start of 2023 behind a rise in e-commerce, a glut of new space that has slowed any further development.

In recent years, though, the region has changed, as a growing population, shifting economic trends, and a metastasizing affordability crisis in neighboring regions has driven more people, wealth and development east from the coast. It can be hard to generalize the sprawling Inland Empire, which includes 4.5 million people covering roughly 30,000 square miles, an area about the size of South Carolina (with a population about that of Kentucky). But communities across the region have exemplified a national trend of more diverse, growing suburbs.

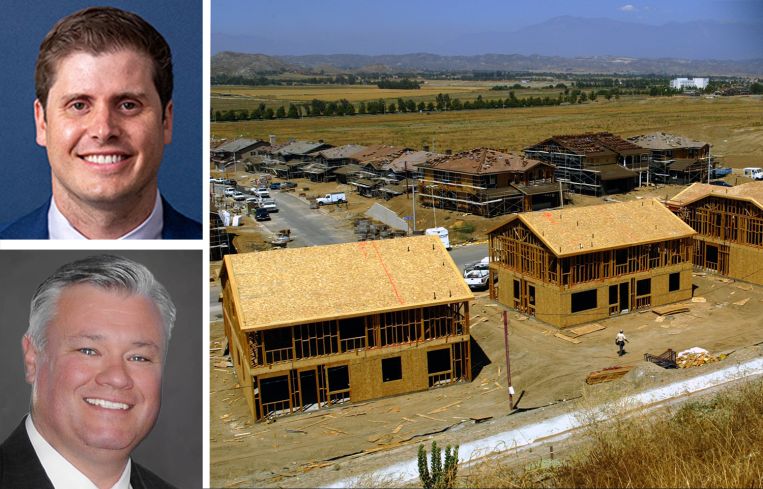

Riverside County has led California in population growth, increasing 6.1 percent between 2015 and 2024 to hit 2.44 million. Drive along Interstates 91, 15 or 215, and new neighborhoods of single-family homes will be easy to spot. It’s why the Urban Land Institute called this market one to watch in 2025, a growth story that flies in the face of the “everyone is leaving California” narrative.

“The population base is growing and there’s a shortage of affordable housing, so that’s really driven the rental market,” said J.C. Casillas, managing director of research at NAI Capital.

As more people move in, the region’s labor market has also exploded, with the workforce expanding by 18.4 percent since 2010. A logistics economy has made way for more clean tech, biotech and advanced manufacturing, like Ohmio, an autonomous shuttle company that relocated its headquarters to the Inland Empire in late 2023. Health care, in fact, employs more people in the region than the warehouses.

“There are stereotypes, and I think that narrative is shifting,” said Kimberly Wright, economic development manager for Riverside County, which includes the city of Riverside.

Many families, fleeing shoebox-size housing in more expensive Orange, San Diego and Los Angeles counties, have come east for more space, more accessible housing and more buying power. Monthly rent in the region, which averages $2,140, may be above the $1,739 U.S. average, but represents a bargain compared to many coastal California cities. Workers with a hybrid schedule may commute to Downtown L.A. a few days of the week and head back to Riverside or San Bernardino counties for long weekends at home.

These new arrivals, in turn, have set off a wave of retail and housing development. The region had seen a boom in all types of property sectors right before the Global Financial Crisis in 2008, and, up until the last few years, that supply glut was still being absorbed, said Greg Giacopuzzi, vice president of leasing and development for brokerage NewMark Merrill.

But growth in recent years has put more shovels in the ground, and a new generation of projects is just starting to open, with more expected for the next few years, said Giacopuzzi.

Housing is taking off in South Riverside County cities like Menifee, Murrieta and Lake Elsinore. New multifamily projects, such as Begonia Village in Fontana or Arroyo Crossings in Indio, show the potential of denser development, a surge that’s just beginning.

Last year, another 1,340 housing units were added to the region’s inventory for 17.5 percent year-over-year growth, per NAI Capital, with more than 6,800 in the pipeline. There’s even a push farther east toward the desert to cities like Cali Mesa, Beaumont and Yucaipa, and, in the high desert city of Hesperia, the 9,366-acre Silverwood master-planned community, boasting thousands of new homes, opened small residential sections last fall.

There’s also significant mixed-use development in the works around Rancho Cucamonga, which will be the western terminus of the Brightline, a 218-mile high-speed rail project currently under construction that will connect L.A. to Las Vegas. A project called The Resort, adjacent to a transit-oriented district surrounding the Brightline station, will include 3,450 housing units and 222,000 square feet of new retail. Another project approved in 2023 seeks to redevelop 56 acres surrounding a nearby minor league ballpark.

Retail in the region has evolved in parallel. The growing number of younger, more affluent consumers means brands that might have been relegated to high-rent coastal markets — such as Cava Grill or Mendocino Farms — are looking for a foothold in the Inland Empire. Specialty grocery stores are duking it out for space in new developments, like Asian specialty grocer 99 Ranch, which opened in a new Eastvale shopping center. Roughly 380,000 square feet of new shopping space was added in the first half of 2024, more than double the amount the same time last year, per NAI. Rents remain 20.1 percent higher than before the start of the pandemic in 2020. In September, national firm MCB purchased a 273,425-square-foot shopping asset in Fontana for $64.7 million.

The latest project NewMark Merrill worked on, Rialto Village in South Rialto, landed a Sprouts Grocery, an Ulta and a Five Below, all in a community that’s typically been viewed as more lower-income. The same forces bolstering retail activity have also brought more medical care and medical office space to the region, including elder care and dental offices.

While absorption of new retail space has been negative in recent quarters in the Inland Empire — just like the rest of SoCal, due in part to a rightsizing in leasing — there’s a sense that underlying fundamentals bode well for the market.

The Inland Empire has suffered from the same interest rate uncertainty that has made multifamily and ground-up retail in particular harder to pencil out nationally. And prices continue to increase for housing, replicating the affordability crunch that drove many to the area in the first place. But, as rate cuts reset the development calculus, there’s hope that the region’s favorable demographics will continue to make it a destination for capital and home to growing communities.

“There’s a lot of demand — not just by retailers, but by consumers — for more choices and more retail out in that area,” said Giacopuzzi. “We’re certainly searching for opportunities.”