New York City Residential Brokers Suffer Setbacks Amid New Laws, Tech

Changes have winnowed the ranks but left behind opportunity for savvy survivors

By Anna Staropoli January 14, 2025 9:00 am

reprints

If you could get past the initial hurdles like developing leads and getting a license, brokering residential deals used to be a surefire path to financial wherewithal in New York City.

Now, though, the field of brokerage — either rentals or sales, on either the tenant or landlord side of a deal — might be tougher than at any time this century.

Within the last few years, successful brokers have maneuvered amid a range of obstacles: the rise in third-party listing aggregators and similar technologies, the continued merging and consolidation of brokerages, historically high mortgage rates, and the pandemic’s hit to housing. They also had to deal with new legislation, including the city’s recently passed ban on many rental broker fees and 2019’s tenant-friendly state rent regulations.

“The residential brokerage landscape is undergoing a profound transformation, shaped by the interplay of technology, legislation and evolving market dynamics,” Jenny Lenz, managing director at Dolly Lenz Real Estate, told Commercial Observer via email.

The number of Manhattan home sales declined 10.7 percent quarterly in the fourth quarter of 2024, according to brokerage Douglas Elliman and appraiser Miller Samuel. The number of new leases dropped 20.8 percent in November, per Douglas Elliman and Miller Samuel, and 5.1 percent in October.

Sales, of course, cliff-dropped during the pandemic’s early years. Miller Samuel research showed a 35.4 percent decline in the number of sales over the two years to the first quarter of 2023.

As transactions have generally trended down and mortgage rates have gone up, many residential brokers have found themselves sidelined or have left the industry altogether, industry insiders say.

“Given the impact of COVID and the sluggishness of the housing market over the last few years, it would not be surprising if there were less brokers than five years ago,” James Whelan, president of the Real Estate Board of New York (REBNY), told Commercial Observer via email. “Thankfully, COVID is further and further behind us and the housing market is starting to rebound, which should entice more individuals to enter the profession.”

To be clear, Whelan and his group can’t confirm or dismiss trends in the residential brokerage field. The official numbers just aren’t there. New York’s Department of State doesn’t distinguish between residential and commercial brokers. Records therefore don’t single out licensed residential brokers.

Department of State data, however, does show that the number of licensed brokers as a whole has declined almost 12.5 percent over the past five years, falling from 54,093 licenses in 2020 to 47,358 in 2024. Every year in between saw a gradual decline in overall brokers, with the number dropping by hundreds — and even thousands — year-to-year.

Although the data for residential brokers specifically remains unclear, anecdotal evidence is mounting that, indeed, shows a shifted landscape — one that rewards brokers who have industry connections, a sharper knowledge of the residential market and an ability to adapt. These brokers are rising to the top, not only in spite of residential real estate’s unique challenges, but also perhaps because of them.

“The residential brokerage industry has been more highly regulated than the commercial industry,” said Stephen Kliegerman, president of Brown Harris Stevens Development Marketing. Overregulation may protect consumers, he added, but it also creates problems in other ways.

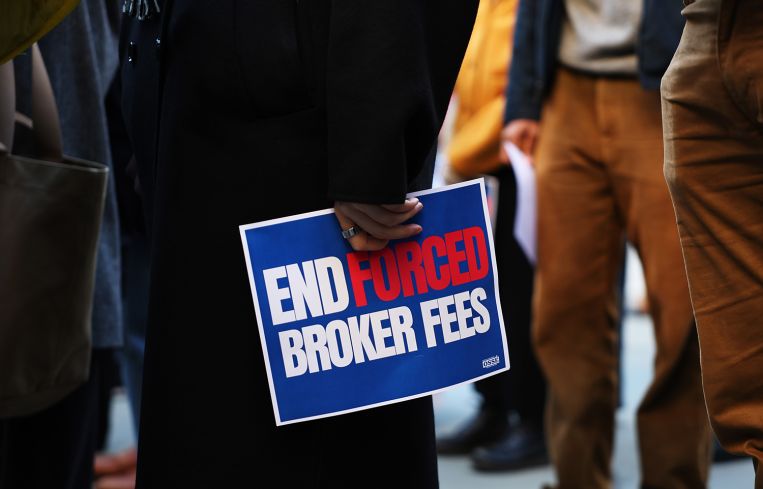

Take the broker fee ban, or Fairness in Apartment Rental Expenses (FARE) Act, which saddles landlords, rather than tenants, with steep broker fees if the landlords hire the brokers who bring in tenants. The fee is usually equivalent to a month’s rent.

Passed in December, the act won’t come into effect until mid-2025, and the rule will affect only select parts of the market, as many New York City tenants work directly with owners and circumvent broker fees entirely, said Andrew Barrocas, CEO of New York’s MNS Real Estate. However, new rental laws cause marketplace confusion regarding brokerage commissions, Barrocas said. Others agree.

“[The broker fee law is] less about addressing affordability and more about political positioning,” said Lenz. “Rather than providing real relief to renters, it shifts costs in ways that may ultimately drive rents higher, as landlords inevitably incorporate these fees into rental prices. The law doesn’t solve the underlying issues of affordability — it merely redistributes the burden, often at the expense of agents and the market’s fluidity.”

Although a hindrance for residential brokers — REBNY filed a federal lawsuit in December against the broker fee ruling — the new rule may encourage brokers to better educate consumers about brokers’ importance, said Kliegerman.

“Although I’m not advocating for the change, I think that this type of change will have the cream rise to the top,” he said.

After all, brokers — at least the more successful ones — should be able to adapt, especially because regulations are neither new nor limited to the FARE Act. The Housing Stability and Tenant Protection Act of 2019, for instance, negatively impacted the brokerage community, said Barrocas. It led to less turnover in rent-stabilized units as landlords had fewer incentives to make improvements that would allow them to increase rents — including rent increases that could remove the apartments from stabilization. Plus, the 2019 rules made it more difficult to vacate apartments.

“Less turnover, less inventory [and] less availability is less inventory for agents to rent and market apartments,” said Barrocas, who cited the decline in transactions as the most significant explanation for any decline in broker ranks. “That’s what you saw over the last two years when interest rates jumped up as much as they did.”

Without available inventory to work with, brokers may move into another industry that allows them to make more money — though, on the more optimistic side of this challenging environment, fewer transactions also mean more competition, allowing brokers to prove and improve themselves. Barrocas cited the 80/20 rule — generally speaking, that 80 percent of results arise from 20 percent of business activity — suggesting that a small but top-performing percentage of brokers does the bulk of residential deals.

Likewise, the rise in technology is shaping the current environment for residential brokers, with both positive and negative implications for a broker’s longevity. When Barrocas started in the industry two decades ago, people would circle listings in newspapers without knowing the apartment’s address. Now, anyone can Google rentals in a chosen neighborhood and do some of the legwork that traditionally would have fallen under a broker’s responsibility.

“Platforms like Zillow have revolutionized access to property information, empowering buyers and renters but challenging brokers to redefine their roles,” said Lenz. “Today’s brokers are no longer just gatekeepers of listings; they are trusted advisers, strategists and negotiators who provide value far beyond the reach of algorithms.”

Technology therefore has skewed the perception of residential brokers. But rather than limit brokers’ importance or render them obsolete, new tech — like any other market change — has the potential to weed out those with less refined skill sets. The brokers able to survive are those who can best understand a given area’s inventory, listings, landlords and the like in such a way that a third-party platform like Zillow can’t.

“Brokers have a lot more value than just — as some might say — opening a door and running a search, or negotiating,” said Kliegerman. “There’s a lot of legal inside information that brokers can obtain when they have relationships throughout the industry.”

For example, a potential renter or buyer may not be privy to some information about a building’s sale prior to its closing, as oftentimes not all information is transparent. While newer brokers may struggle to obtain such details, brokers with more experience can leverage their industry connections and find a way to get that information off the record, and then provide it to their clients, said Kliegerman.

Technology, therefore, may be changing real estate’s climate, but it works best in tandem with brokers rather than as their replacement. “Whether it’s Zillow, StreetEasy, and the like, [aggregators] provide exposure for listings. But what they don’t replace is the boots-on-the-ground experience and the knowledge behind the information that’s provided on these websites,” said Kliegerman.

The best brokers tend to take the time to be thoroughly prepared. If prospective tenants are looking to buy or rent across New York City, for instance, a broker must know the fabric of every location, from the Upper East Side to Brooklyn Heights, and exercise a widespread level of expertise that increases business.

“A really good broker is like any other really good professional,” said Kliegerman.

He differentiated between technology’s listing aggregators and technology’s help tools that can enhance a broker’s business, as technology not only spurs a survival of the fittest culling but also helps brokers help themselves. Customer relationship management (CRM) technology allows brokers to better communicate with their networks and past clients, while digital platforms help brokers educate themselves on the status of a particular neighborhood’s listings, analyze marketplace trends, and obtain information like floor plans, said Kliegerman.

Yet, whether with changing technology, new laws or rising interest rates, “if you are an established agent, you’re going to change with the tides,” said Barrocas, who initially worked predominantly with tenants before expanding his reach to the property and landlord side. “There have been several times where the market has changed and different restrictions have come into play, and I think it’s important to be flexible and be able to adapt your business model to adjust to the times you’re in.”

MNS, as such, has not seen a decline in brokers, which Barrocas attributed to the company’s model focused on landlords and developers. Meanwhile, per Kliegerman, there seems to be an increase in professionals from other industries — such as financial planning, money management and accounting — pursuing careers in the residential brokerage community.

Yet, if these potential brokers really want to last in the industry, one attribute may serve them best: “Residential brokers, first of all, are incredibly resilient,” said Kliegerman. “The fabric of a residential broker is one to innovate and roll with changes.”

Anna Staropoli can be reached at astaropoli@commercialobserver.com.