New York City’s Multiple Dwelling Law Is History — Here’s How It Happened

The rules dating from 1961 limited the density of new residential developments

By Brian Pascus January 15, 2025 6:00 am

reprints

As New York City grapples with a long-simmering housing crisis, an obscure zoning regulation passed in 1961 has been targeted by politicians, developers and city planners as the reason too few homes have been built in the five boroughs over the last 60 years.

Last April, lawmakers in Albany passed a budget that amended the state Multiple Dwelling Law, which had not been changed in those intervening six-plus decades, when lawmakers altered it to coincide with sweeping city zoning changes. The 1961 changes had placed a seemingly arbitrary cap on what’s called the floor area ratio (FAR) — the ratio between a building lot’s footprint and its usable square footage of floor space — that then restricted residential housing development in New York City ever since.

Just last month, local lawmakers did their part, passing the first stage of Mayor Eric Adams’s ambitious City of Yes agenda, which grants the city the right to create two new zoning districts that exceed the current FAR cap of 12 times its lot footprint. The change will allow residential construction to far exceed current floor space limits imposed by what has widely been considered an outdated restriction created by the 1961 state law.

For housing experts, particularly previous Gracie Mansion vets, the amended zoning laws are necessary to produce more housing units in the nation’s most populous city.

“The housing crisis is real for the city; it’s both an equity issue and an economic development issue,” said Carl Weisbrod, chairman of the New York City Planning Commission under Mayor Bill de Blasio. “If we have 50,000 people in homeless shelters, and many families that can’t remotely find an apartment, much less pay rent, it’s harder to attract talent and keep talent in the city if they can’t find an affordable place to live.”

For much of New York City’s history, housing production wasn’t an issue. The city produced a staggering 729,000 multifamily units in the 1920s, 322,000 units in the 1950s, and 369,000 units in the 1960s, according to city data.

But, once the limits imposed by the 1961 Multiple Dwelling Law amendment and its 12 FAR cap fully went into effect after a multiyear grace period, production dwindled. The 1980s and 1990s produced only 184,000 units of new housing combined.

“From 1968 to 1978 the city went into recession, the population declined 800,000, so there was no pressure on real estate values as we have today, until 2000, at least,” explained Jason Barr, professor of economics and urban studies at Rutgers University. “There were problems of housing affordability on the low end of the income scale, but this idea of massive affordability problems, and not enough buildings to live in, wasn’t on people’s radars.”

By the 2010s, even after the targeted zoning reforms initiated by mayors Michael Bloomberg and de Blasio, New York City created only 185,000 new units of multifamily housing, though the city’s population increased by 600,000 residents.

Today’s demographics are making city planners nervous. Barr estimates that New York City currently has 8.6 million units of housing for a population of 8.2 million. With conservative population increases of 2 percent per year, the city will need to build 50,000 new units annually through 2030. Yet current average production is closer to 25,000 new units per year.

“You need to double production to get the city out of a housing crisis,” he said. “And it needs to be in the Bronx, Queens and Nassau County. It has to be in places where rich people don’t want to live.”

To understand why an obscure zoning law regulating floor area ratios essentially froze New York’s ability to build residential housing, a little math and even more imagination is required.

FAR from simple

A 12 FAR cap means the amount of floor space built on a lot cannot exceed 12 times the size of the lot itself.

If a building is occupying an entire footprint at 1,000 square feet in Midtown Manhattan, it can go to 12 stories. But, if it’s occupying only half of that lot, it can build no more than 24 stories. At one-third of the lot, it can build 36 stories, while a quarter of the lot occupied brings out 48 stories.

But a FAR cap of 12 isn’t so much a function of stories as it is of bulk: a bigger building can be built on a bigger piece of land. If a developer has a 10,000-square-foot lot, there’s 120,000 square feet of buildable space (multiplying the lot size by 12). With a 20,000-square-foot lot, one can build 240,000 square feet. But that bulk can either be a wide 10-story building that covers an entire lot or a taller 40-story building on a quarter of the lot. It comes down to the square footage allowed by the 12 FAR multiple.

“What 12 FAR does by limiting bulk is it allows you to limit building shape from a fat, squat building to a taller, thin building,” explained Barr. “The taller you go, the more open space there has to be on that lot. That’s the fundamental law: The footprint shrinks.”

Ironically, the 12 FAR cap applies only to residential buildings. Commercial buildings have been granted the ability to build under a FAR cap zoned as high as 33 FAR in East Midtown, according to the Real Estate Board of New York (REBNY). Even landmarks go higher: The Empire State Building has a FAR more than 30, while the Chrysler Building carries a FAR of 27.

“There’s a limit on how much residential density [a building] can have, and to me that never made a lot of sense. If we all agree that a neighborhood can accommodate some very large buildings, there’s no reason why it can’t be full of apartments,” said Jed Resnick, CEO of Douglaston Development, a residential developer in New York. “There’s a recognition that we have too much office space and not enough residential space in New York City.”

But that recognition has come several decades after lawmakers had already put a veritable lock on how high residential buildings could and how many units could fit under their roofs.

“It’s only now, in the last 10 or 15 years, where people have woken up to the idea that with the 1961 Multiple Dwelling Law, they really put a glass dome over the city,” said Barr.

Long time coming

The 1961 Multiple Dwelling Law with the 12 FAR cap has its origins in one concern: crowding, known to city planners as “density.”

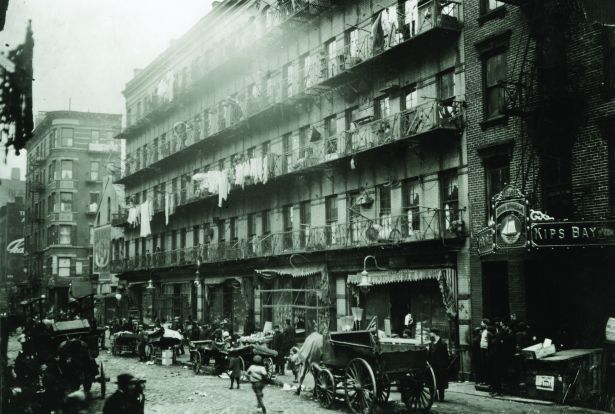

New York density concerns go back to the early 19th century, at the time of Five Points and Bill the Butcher, fodder for films like Martin Scorsese’s “Gangs of New York.” Overcrowded, crammed dwellings continued being built into the Gilded Age, when immigrants arrived by the millions and makeshift tenements were created across Lower Manhattan to house a new underclass.

“The Lower East Side in the 19th century was one of the densest neighborhoods in the world — there were no laws about how things were built, there was nothing,” said Kevin Draper, a city historian and co-founder of New York Historical Tours. “You had shoddy construction, and, even if buildings were built solid, there were no laws about how many people could fit into the apartment. You’d have a family of 10 living in the studio apartment.”

Slowly but surely, New York City initiated building codes, notably the far-reaching 1916 zoning reform, which some city planners believed had zoned the city to provide residences for up to 55 million people, largely through unrestricted residential and industrial development. New York also reformed its tenements and subway system, essentially consolidating the five boroughs as we know it.

By the 1920s, however, the widespread arrival of the elevator birthed the modern skyscraper. Developments like the 1915 Equitable Building at 120 Broadway — a 1.2 million-square-foot neoclassical structure of brick and granite — alarmed city planners due to its lack of setbacks and the overshadowing nature of its bulk. The consensus was that, without reforms, the 1916 zoning code would eventually allow the city to become too big, too crowded and too dense.

“The conversation around reforming the zoning code from the 1940s to the 1960s was about housing quality, open space, light and air, and how to prevent crowding and slum conditions,” explained Moses Gates, vice president of housing and neighborhood planning at the Regional Plan Association. “The highest density that planners thought appropriate for residential development in Manhattan was 12 FAR.”

The state passed the 1961 Multiple Dwelling Law while the city simultaneously amended the 1916 zoning resolution, thus locking the 12 FAR cap into place.

“There really wasn’t any empirical basis for the 12 FAR cap. There was an idea that larger residential buildings lead to overcrowding, health problems and so on, but it wasn’t like there was some study they were relying on,” explained Elise Wagner, partner and land use attorney at Kramer Levin.

For the first few decades after the 1961 Multiple Dwelling Law went into effect, housing production declined. At the same time, the city’s population shrank amid rising crime and multiyear budget crunches, hitting a modern nadir of 7 million souls in 1980 and 7.3 million in 1990 from a high of 7.8 million between 1950 and 1970.

Residents fled to the suburbs, and the 12 FAR cap didn’t cause much concern, as more people chose to use the city for its office buildings rather than its brownstones.

Under declining demand, New York’s residential market proved to be affordable in the 1980s and 1990s, Draper said, and more middle-class folks could buy into brownstones and apartment buildings (especially after a wave of co-op conversions in the 1980s). Rental vacancy rose as high as 6.9 percent in 1996, according to the Federal Reserve. But, as quality of life improved, the population broke past 8 million by the 2000 census, with rising demand occurring at the same time the 12 FAR cap hindered new construction.

Draper added that by the 2000s the city had turned into “a luxury product,” where a newly emboldened international set sought to invest across a network of increasingly pricey hard assets like luxury condominiums — which were going up some years by the thousands — and bulky, unit-heavy, pre-1961 multifamily properties.

“It’s almost like we’re a victim of our own success,” Draper said. “New York became a great place to live and invest in, but now the average person can’t buy a brownstone to renovate, and it’s no longer worth it for a developer to build middle-income housing when he can build super-tall luxury housing.”

What will the neighbors think?

Vicki Been, who served as commissioner of the New York City Department of Housing and Urban Development and then as deputy mayor for housing and economic development, said that the de Blasio administration tried for years to amend the 1961 Multiple Dwelling Law. Pushback came from two corners: preservationists, who feared amending the law would harm the aesthetics of the city, and residents, who abhorred potential changes to the character of their neighborhoods.

“People really do fear more density,” said Been. “They fear that it will make ‘my subway’ and ‘my schools’ more crowded, that it will bring new stores and destroy what ‘I like about my neighborhood’ because it’s change.”

The Municipal Art Society of New York authored a letter to Gov. Kathy Hochul in 2022, trying to dissuade her from amending the 1961 Multiple Dwelling Law, arguing that “many city neighborhoods are dense already,” and that any belief that lifting the FAR is necessary to create more density is “unfounded.”

Then there’s Billionaires’ Row. The construction of supertall, ultraluxury residential structures — 432 Park, One57, Central Park Tower, 111 West 57th Street and 220 Central Park South — across 57th Street in Manhattan helped create the perfect boogeyman when it came to arguing against lifting the 12 FAR cap for greater residential density.

“People see a lot of supertall buildings, and supertall doesn’t mean you have unlimited FAR, but people associate that with uber-luxury apartments, and they don’t know why New York should become a playground for the rich,” said Been.

Ironically, the 12 FAR cap and existing zoning laws are the reasons why developers have been able to build 100-story towers where condos routinely sell for eight or nine figures in the first place, while affordable housing developers have been limited to much shorter structures. This comes down to two zoning concepts: as-of-right development and air rights.

So long as a development complies with existing zoning laws, a New York developer can build in whatever manner without a complex review process. This concept is called as-of-right zoning.

But, even if a supertall luxury development stays within the maximum 12 FAR zoning limit, a developer can still buy the unused FAR — or air rights — of neighboring buildings, thus doubling, tripling or quadrupling a property’s lot size, especially if the properties are zoned as contiguous, taking advantage of a chain of low-lying buildings with unused FAR.

Billionaires’ Row developers “took air rights from six buildings in a row, down the block, because the zoning resolution allows you to do it through zoning lot mergers — you pay adjacent owners for the value of their air rights,” said Wagner.

Supertall condos also can occur because FAR limits cover only floor space, not ceiling heights. FAR doesn’t prohibit an ultra-luxury building with 20-foot ceilings on each story, or with a soaring 40-foot-high ground-floor lobby designed in part to improve second-floor views.

Predictably, most developers of market-rate housing can’t pencil in these types of purchases. Meanwhile, ultraluxury developers use their air-rights chains to build tall, skinny condos while shrewdly adhering to the 12 FAR density limits, as most of their units individually cover three to five floors, keeping occupancy low.

A new day

By the time the Adams administration took power in January 2022, New York’s housing crisis touched every corner of the city, and residents realized outdated zoning laws needed reform.

A 2016 analysis reported by The New York Times of 43,000 buildings across the five boroughs found that 17,000 of them, or 40 percent, did not conform to at least one part of the 12 FAR zoning code and could not have been built under current regulatory standards.

Moreover, certain neighborhoods, especially those outside Manhattan, have been zoned for virtually no dense residential housing. Several districts — notably R1s, R2s and R3s — have FAR caps between 0.5 and 0.9, according to the REBNY.

“People are waking up to the fact that there really is a very serious housing crisis in New York, probably the most significant economic crisis the city is facing,” said Weisbrod, the former Planning Commission chair. “We need more housing and we need bigger buildings as well.”

After long-delayed action by Albany, the New York City Council passed Adams’s City of Yes housing amendments, which create two new districts, R11 and R12, with FARs of 15 and 18, respectively. Elected officials and community groups still need to assign where these districts will go, but Midtown South — below 42nd street, above 29th street — has already been targeted for denser residential zoning.

Basha Gerhards, REBNY’s senior vice president for urban planning, said that these City of Yes reforms will create pathways for more office conversion and other new housing production in transit-rich areas all across New York.

“This should be the first of many policy actions to address our housing crisis,” she added.

Gates said that the Regional Plan Association is glad to see the 1961 Multiple Dwelling Law finally be amended, as the debate around density and housing in 2024 is far different than it was in 1961.

“We have a different city with different concerns and different technology and we need to update our rules accordingly,” he said. “Rules that might have made sense 60 years ago don’t make sense now.”

Brian Pascus can be reached at bpascus@commercialobserver.com