Last Chance Commercial Real Estate

Office landlords who defaulted on their own loans are being trusted with the keys again after raising billions for distress

By Brian Pascus May 14, 2024 9:00 am

reprints

For much of 2023, Commercial Observer headlines noted the struggles some of the nation’s largest office landlords experienced as interest rates rose, vacancies surged, demand crashed, and property values tanked.

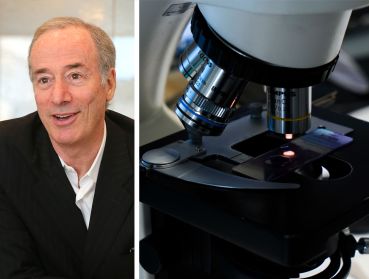

Last May, RXR Chairman and CEO Scott Rechler walked away from a 33-story office tower at 61 Broadway in the Financial District after defaulting on a $240 million loan that matured. Today, however, the loan is now being worked out.

In December, Savanna handed back the keys to 1825 Park Avenue, a 12-story office building in Harlem that carried a transfer value of $56.2 million. The deal was a deed-in-lieu, which is usually considered a less messy type of disposition than pure foreclosure.

And then there’s SL Green, New York City’s largest office landlord. CO reported last fall that three of the firm’s prime office towers — 245 Park Avenue, 280 Park Avenue and One Worldwide Plaza — either appeared on special servicing watchlists or failed to pay their loans at maturity. (So far this year, SL Green has done about $2 billion in extensions and restructurings.)

“It’s an interesting phenomenon,” said Thomas Taylor, senior CRE and CMBS researcher at Trepp. “It’s really a result no one wants, especially at this scale and institutional size, but it’s concentrated in key metro areas.”

And then a funny thing happened. These same landlords who handed back the keys or presided over underwater assets announced they were forming

billion-dollar debt vehicles to buy up even more distressed office buildings.

Over the last six months, SL Green announced its intention to launch a $1 billion debt fund devoted to investment opportunities in distressed New York City real estate, particularly office; RXR and Ares Management formed a $1 billion joint venture fund to invest in distressed office; and Green Street reported in March that Savanna formed its own credit fund to invest in distressed office, one that is also targeting $1 billion in equity investments.

“We can’t completely get inside the minds of the LPs cutting these checks, or inside the CEOs who will bet on themselves to make better decisions than their past selves,” explained Trepp’s Taylor. “But if I had to surmise … the biggest takeaway for us is lots of markets are doing well and we see an opportunity to get in at a good basis with these new funds.”

But it begs the question: Why should these landlords be trusted to make better decisions when they’ve already evinced unfavorable outcomes with some of their other once-prime office properties?

Meghan Czechowski, head of appraisals at Walker & Dunlop, said that the wave of distress since COVID-19 and the era of higher interest rates has changed the valuation game for almost all office properties, and that distressed investment — even from previously wounded landlords — is a necessary ingredient to ultimately correct valuations across the market.

“It all comes down to resetting the basis, which is what these owners need to do in this environment,” said Czechowski. “This market is providing major opportunities to buy at a lower cost basis, particularly the office market, which allows base costs to reset, where investors can ultimately carry out their investment plan to achieve anticipated returns.”

Too bad that type of “resetting” doesn’t work for homeowners or renters after a missed payment!

Brian Pascus can be reached at bpascus@commercialobserver.com.