Debt Default Could Prove Catastrophic for Commercial Real Estate: Here’s Why

The interplay between Treasurys and asset pricing means a hit to U.S. creditworthiness would be a knockout punch to much of CRE financing

By Brian Pascus May 17, 2023 1:41 pm

reprints

This can’t be what the Founding Fathers had in mind.

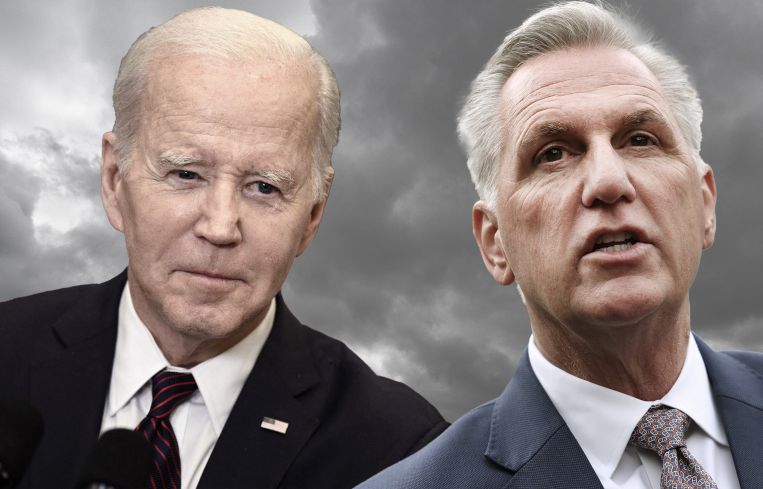

President Joe Biden and House Speaker Kevin McCarthy ended their May 16 meeting at the White House — their second such gathering in one week — without any consensus on how to generate a congressional agreement to raise the nation’s debt ceiling before a June 1 deadline set by the Treasury Department. And last week, during a May 10 CNN town hall, former president Donald J. Trump urged congressional Republicans to enter into default. The following morning, Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen called the suggestion of default “unthinkable,” and implored lawmakers to compromise.

If this sounds like serious business, rather than political bluster, it’s because economists and commercial real estate executives are increasingly concerned that Republicans are willing to breach the nation’s $31.4 trillion debt ceiling and Democrats are unwilling to concede to GOP demands for government spending cuts, notably to recent Biden administration climate initiatives and COVID-19 era emergency policies.

“There’s a game of chicken in Washington right now and we’re waiting to see who blinks first,” said Sam Chandan, director of NYU Stern Chao-Hon Chen Institute for Global Real Estate Finance. “Irrespective of whether we arrive at an agreement, there’s an understanding that this is proving to be very damaging to U.S. credibility. [Default] would upend one of our most fundamental assumptions of how the global financial system works — the characterization of Treasuries being risk-free — if the U.S. fails to meet its obligations.”

The U.S. national debt is allowed to grow only so long as Congress raises the fiscal ceiling of borrowing costs to coincide with the annual need. The U.S. hit its borrowing limit in January, and Yellen has said that the Treasury will run out money to pay its bills as early as June 1, though this date can extend into early July, without a congressional agreement to spend more money, and thus issue more debt.

Most government debt is funded by the sale of U.S Treasurys -– T-bills, T-bonds and T-notes -– into the global economy, which are seen as risk-free bonds that serve as the benchmark interest rate for all other forms of corporate, financial and municipal debt in the United States. And because of the interconnection between Treasurys and the global financial system, commercial real estate executives at even the largest firms are bracing for unprecedented disruption in capital markets if the creditworthiness of Treasuries is called into question by the nightmare of default.

“The uncertainty affects everybody and default is the last thing this country, or our industry, needs as we struggle with this uncertainty,” said Jeffrey Gural, chair of GFP Real Estate. “All of us are just assuming they’re going to solve it because there’s nothing else we can do. If we really thought we’d default on our debt, we might as well leave the country.”

For a market that has seen interest rates rise 5 percentage points in 14 months — and inflation reach its highest levels in 40 years — along with an ongoing financial crisis that has seen the second-, third- and fourth-largest bank failures in U.S. history within the last two months, the economic upheaval caused by government default would be akin to dropping a Molotov cocktail into a warehouse full of dynamite.

“Breaching the debt ceiling will be the icing on the cake for an absolutely tumultuous time,” said David Schechtman, senior executive managing director at Meridian Capital. “No one [in the industry] is screaming about the debt ceiling yet, because we’re too busy talking about three to four other major catastrophes that have happened in the last couple of months.”

That complex relationship that Treasury yields have with the entire capital markets ecosystem is what makes the debt ceiling breach such a dangerous threat to commercial real estate interests. By serving as the benchmark for interest rates across the wider economy, Treasurys hold the keys to how credit is facilitated among parties. Default would immediately devalue the worth of treasuries, subsequently increasing the risk associated with holding them. That would in turn raise yields on every other interest rate across the financial system, notably mortgage bonds and corporate bonds.

“That’s the problem with this: we go from having a strong, confident, risk-free Treasury rate, to something where there is less confidence and now there is a risk premium put on top of the Treasury, the benchmark, and that’s when yields start to go up,” said Thomas LaSalvia, director of economic research at Moody’s, a credit rating agency. “A whole new series of risk premiums associated with the Treasury would appear across the industry, and that’s what makes money more expensive.”

Even more concerning for CRE beyond the cost of credit is the threat higher interest rates sparked by tanking treasury values would pose to the banking system, whose foundations have been rocked in recent weeks by a wave of bank failures. Silicon Valley Bank, Signature Bank and First Republic Bank all died not due to bad loans, but, among other things, because their treasury holdings took such a steep loss in value from the rate hikes engineered by the Federal Reserve. Other causes for an increasingly complex banking crisis include the cryptocurrency industry imploding, dangerously uninsured depositor levels, and asset-liability mismatch.

But the value of Treasury holdings within the entire banking network would plummet a great deal further if the cause was the imminence of actual default on U.S. Treasury obligations, rather than mere monetary policy, noted Robert Hockett, professor of corporate law and financial regulation at Cornell School of Law. Such a cause would place institutional solvency at the forefront of the crisis.

“My worry is that those banks that hold lots of real estate on their portfolios — including mortgage-backed securities — because they also hold lots of Treasurys, they’d begin to tumble really rapidly,” Hockett said. “And because they are financiers of commercial real estate projects, those who seek the financing would find themselves with fewer options.

“It would do much more than [Jerome] Powell would ever want to see happen,” he added. “It would throw the economy into a steep nosedive — not just an outright recession, but it would reach depression proportions.”

Even in the event that a number of banks survive the consequences of U.S. debt default, those few still remaining would find their ability to underwrite loans severely impacted by the higher cost of financing. And any existing loans would also be called into question.

“I’d expect there to be more loan defaults because of the pressure on interest rates,” said real estate attorney Eric L. Goldberg, a partner at law firm Olshan Frome Wolosky. “There are floating-rate loans today that would get higher, and thus more difficult to refinance, and loans that are in the shop today that people are looking to close, they’d foreclose as the rates go up. It would make an already difficult commercial marketplace that much more difficult.”

For those deals that would be lucky enough to survive the credit contraction and wave of loan defaults, a breach of the debt ceiling would result in “a significant deterioration of value to the dollar in relation to other currencies,” according to professor Chandan, paving the way for skyrocketing inflation, intractable construction costs, and mass unemployment.

“All things we import would become significantly more expensive,” said Chandan. “Material imports, including softwood lumber from Canada, all the construction machinery, everything we import… . It’s an event without precedent.”

So what, if anything, are CRE executives doing to prepare for this economic armageddon?

In anticipation for a worst-case scenario, some are simply throwing up their hands

“We’re not doing anything above and beyond what we’re doing in an already challenging environment,” explained Shawn Townsend, managing principal at Blue Vista Capital Management, a CRE investment firm. “Production volume and debt financing have fallen off the map, so we’re making a shift toward managing the quality of our book and preserving value. You [look at it] through more of an asset management lens rather than just production.”

Others are attending to the present moment, rather than catastrophizing for an unknown future.

“Those like myself are focused on the problem at hand: dealing with the banks and leasing vacant space,” said Gural, whose father founded what became Newmark in 1953. “I’m 80 years old, and this is the hardest I’ve ever worked in my life to get through and preserve what my father and I built all these years, to make sure we keep these buildings leased, that we keep the banks happy.”

And then there are the confident few who believe the entire debt ceiling debate is political theater, who feel they’d be better off expending their energy elsewhere in an increasingly complicated market.

“I’m doing nothing and I don’t think anyone else in commercial real estate is doing anything either because we have bigger fish to fry,” said Shlomo Chopp, managing partner at Terra Strategies, a real estate investment firm. “Does it make a difference that Congress is fighting? They’ve been fighting forever. In reality, it’s a combination of ‘The Boy Who Cried Wolf’ and that we’re desensitized to risk.”

But one section of the market watching the debt ceiling debate with enhanced interest is the debt funds, or alternative lenders, who could be primed to step in and provide capital across the CRE market in the event banks encounter a credit crunch from skyrocketing Treasury yields. These debt funds emerged after the 2007-2009 Global Financial Crisis to provide liquidity for a system that faced enduring credit constraints and augmented regulation and oversight in the years that followed the crash.

“If we get close to default, private lenders are going to become the go-to commodity, and they can charge even more by way of fees and interest rates,” explained Meridian Capital’s Schechtman. “If Fannie [Mae] and Freddie [Mac], who are backstopped by the full faith and credit of the U.S. government, aren’t lending, then Blackstone and their debt funds will have lots of business.”

“I think it will be the greatest boon in history,” he added. “Those funds might be one of the few people left standing for a short period.”

Regardless of whether alternative lenders swoop in to save the day or the entire capital markets economy grinds to a halt, there’s no denying that even the threat of self-induced default has roiled the private sector.

“I think it will get resolved at the last minute, but just because it gets resolved doesn’t mean there won’t be a lot of pain getting there,” said Olshan’s Goldberg. “Interest rates will go up because of the uncertainty, and they won’t go down as soon as the Treasury and Congress resolve the debt limit issue.”

And if Speaker McCarthy’s Republicans decide to walk away from any deal offered by Biden’s Democratic administration, or vice versa, and we hit the June 1 deadline with an empty national checking account?

“In effect, overnight, the U.S. would lose its capacity to be this economic superpower,” said professor Hockett. “How can it pay if the dollar becomes worthless?”

Brian Pascus can be reached at bpascus@commercialobserver.com