Limited Water Resources Could Choke Housing Boom in Arizona

A lot of new single-family homes for sale are going up in Arizona, water supply or not

By Mark Hallum April 19, 2023 8:00 am

reprints

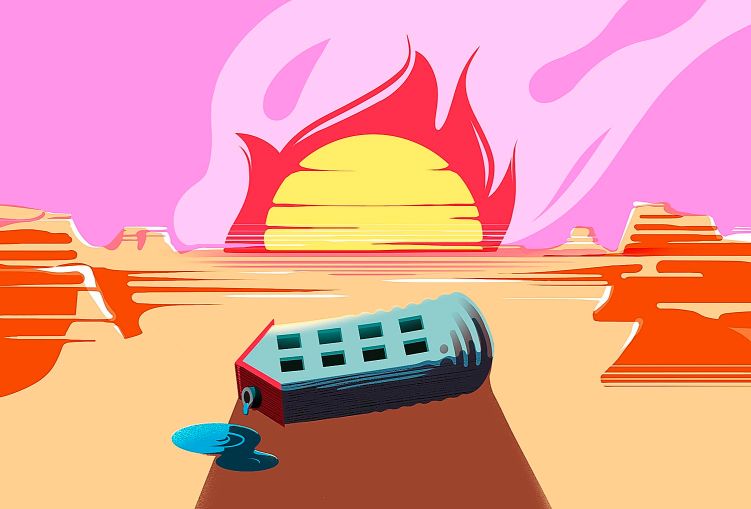

What started as a flood will probably end up like so many dry gullies taking a beating under the sun. We’re not talking about water — well, we are — but we’re really talking about single-family homes.

But housing developers seem unshaken by alarming reactions from government officials and policymakers to a steady stream of findings that, while the population is taking off and cities are sprawling, water supplies are hitting critical levels. Even the playgrounds of the upper middle class like Lake Mead and Lake Powell are turning into fields of desiccation cracks.

Things got real when Gov. Katie Hobbs took over the reins in Arizona from Doug Ducey at the beginning of 2023, and almost immediately released a report allegedly withheld by the previous administration. It said Phoenix’s West Valley is short 4.4 million acre-feet of water over a 100-year period.

Before any construction is approved, developers in the Phoenix region must certify with the state that land they’re about to build on has enough water in the ground to last 100 years.

This is a problem around Phoenix — especially the Lower Hassayampa sub-basin and a small portion of West Salt River Valley sub-basin — where the water supply simply cannot support new homes, according to Hobbs’ administration. The Arizona Department of Water Resources would therefore deny certification to any new proposal that relied on groundwater.

“I do not understand, and do not in any way agree with, my predecessor choosing to keep this report from the public and from members of this legislature. However, my decision to release this report signals how I plan to tackle our water issues openly and directly,” Hobbs said in her State of the State Address in January, just days after taking the oath of office. “We must talk about the challenge of our time: Arizona’s decades-long drought, over-usage of the Colorado River, and the combined ramifications on our water supply, our forests and our communities.”

In other words, the governor is slamming the brakes on a development boom that saw the birth of entire cities in the desert despite a 20-year drought — the worst dry spell the region has experienced in the last 1,200 years.

Arizona’s January wake-up call was also compounded by a disaster at Rio Verde Foothills near Scottsdale, which gets its water from the Colorado River via a 1,000-year-old canal system originally laid out by Native Americans.

The 600-home subdivision built in the 1970s without a water main has shipped water in by the truckload since its construction. With the city of Scottsdale cutting back on water use in the last year, residents were left high and dry; bathing became a veritable luxury and store-bought water a must, according to Time.

Before long, the residents sued the city.

One development taking shape in the patch of desert in question is a 37,000-acre property in White Tank Mountains, where the Howard Hughes Corporation wants to build a master-planned community with 100,000 homes and 55 million square feet of commercial space. For Teravalis, as the corporation is calling the land formerly known as Douglas Ranch, to be realized it will have to prove that it can provide 300,000 residents and 450,000 workers with water, according to The New York Times.

The first phase of the Teravalis development known as Floreo has, however, already secured a 100-year Assured Water Certification from the Department of Water Resources, putting over 7,000 homes in the pipeline.

“We will continue to explore ways to innovate and implement the most modern measures of conservation and reuse so that when the time comes to expand beyond the development of Floreo, we are ready to do so in a way that ensures the prosperous and sustainable future for the West Valley — remaining, as always, in close collaboration with key stakeholders throughout the region,” Heath Melton, president of the Arizona region for Howard Hughes, said in a statement.

The company did not make immediately clear what kinds of sustainability measures it plans to take.

Sarah Porter, director of the Kyl Center for Water Policy at Arizona State University, expects more restrictions on housing developments in the southeastern side of the greater Phoenix area, in what is known as the Salt River Basin, when another groundwater report is released in the coming days.

Even so, these revelations have done little to stop the majority of new subdivisions that were in the works well before Gov. Hobbs’ January moves and already certified that they physically, legally and financially would have access to water resources, according to Porter.

“For some time, developers have been proving the supply based on the groundwater in aquifers right beneath the developments, and the Department of Water Resources has done modeling … and concluded that the groundwater is fully allocated,” Porter said. “Developers can no longer use the groundwater right there as the water supply for the subdivision. … [But] there are years and years of yet-to-be-built developments that have already obtained assured water supply certificates.”

In terms of policy changes, Porter said that the certification process itself does not need overhauling when it comes to protecting potential homeowners.

“Developers think that anything that would allow them to continue to develop would serve the greater good. I’m being snarky, but there isn’t a consensus about what should be done,” Porter said. “I would say that we should stick to the policy that’s in place so that we can make sure that when people buy a home in Phoenix or Tucson that they can be sure that they will have a water supply for that home.”

Housing developments within city limits of Arizona’s major population centers only need to prove every 15 years that they can meet the current demands of residents. This means cities in the desert have been able to grow. Rental homes aren’t subject to the same certification — which is viewed as much as a consumer protection as an environmental one — because tenants are ostensibly not making lifetime commitments.

“The consumer protection aspect doesn’t really apply,” she said.

Another of Hobbs’ first courses of action was to issue an executive order that created the Water Policy Council tasked with bringing the 43-year-old Arizona Groundwater Management Act into the 21st century and preventing unnecessary — or unscrupulous — waste.

Hobbs and state Attorney General Kris Mayes, also newly elected, are attempting to close loopholes that allow unfettered groundwater pumping in La Paz County by Fondomonte, a subsidiary of Saudi Arabian alfalfa grower Almarai. Almarai uses the H2O to produce the grass in Arizona, which it then ships off to Saudi Arabia, where growing alfalfa is illegal due to the high amount of water required.

The company’s farms operate under a lease agreement with the state, which Mayes believes should constitute an illegal gift by the government under Arizona’s constitution. She plans to end the agreement within six months and collect $38 million in back pay for water used.

In Pinal County, which sits just south of Phoenix and is mainly agricultural, Water Resources put a stop to all new-home construction in 2021 due to excessive pumping. Despite the moratorium, Casa Grande, a city in Pinal, saw up to 700 rental homes approved last year due to another loophole: the 100-year water guarantee doesn’t apply to build-to-rent communities, only to for-sale housing.

While groundwater accounts for 41 percent of Arizona’s water supply, the rest comes from the ailing Colorado River, which for decades has supported the populations of cities such as Los Angeles, Las Vegas and Phoenix. Altogether, the river provides drinking water to 40 million as well as to the states of Sonora and Baja California in Mexico.

The conservation measures by the Hobbs administration were followed by a mandate from the Biden administration announced April 11 that California, Arizona and Nevada would each have to cut their water usage from the Colorado by about a quarter each. For Arizona, that means water allocations from the Colorado will be cut by 600,000 acre-feet a year, according to Hobbs.

“The system is approaching a tipping point, and without action we cannot protect the system and the millions of Americans who rely on this critical resource,” Camille Calimlim Touton, commissioner of the Bureau of Reclamation, said in a press conference at the time.

Mark Hallum can be reached at mhallum@commercialobserver.com.