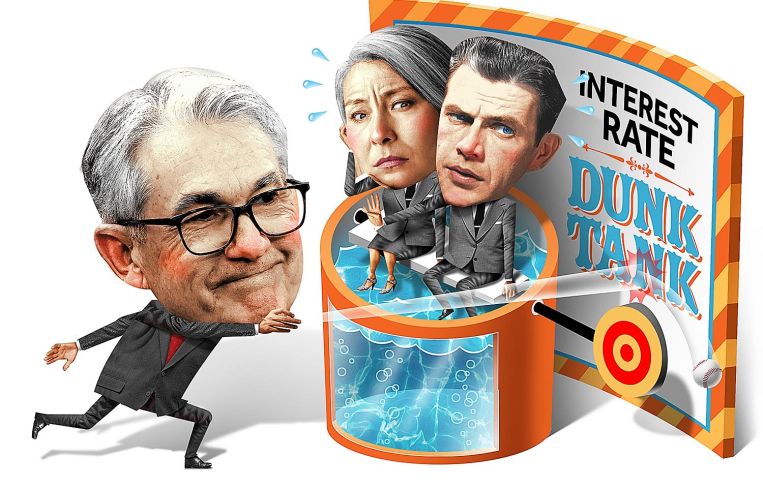

Rising Interest Rate Cap Costs Pressure CRE Borrowers

Property owners try to avoid going underwater as the costs of protections against floating-rate debt rise

By Andrew Coen March 7, 2023 9:49 am

reprints

Soaring costs for protections against rising interest rates are further pressuring commercial real estate property owners saddled with floating-rate debt.

Property owners who purchased interest rate caps before the Federal Reserve began sharply raising interest rates from near zero last year are feeling particular pressure. That’s because these caps are set to expire soon, just as the cost of these hedges surges. Lenders typically require interest rate caps for deals involving floating-rate borrowing, which comprises about a third of all commercial real estate debt, according to the latest Mortgage Bankers Association

data.

“These interest rate caps have become a meaningful part of the deal economics right now, whether it is a new deal or an extension of an existing deal,” said Chris Moore, managing director at Chatham Financial, an advisory firm that arranges interest rate cap deals. “If you look at the prices from February of last year versus the prices today, there is pretty meaningful change.”

The Fed raised interest rates seven times in 2022, starting with a modest 25 basis point increase on St. Patrick’s Day, followed by a half-point jump on May 5. The central bank then implemented the first of four straight hikes of 75 basis points from June through November before a half-point rise in December and a quarter-point increase in January.

Prior to the start of the Fed’s run of eight consecutive rate increases, bringing the federal funds rate up to between 4.5 percent to 4.75 percent, interest rate caps were a fairly modest monetary part of the CRE financing process. Dramatic changes in the Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR) forward curve, which Moore described as the “betting line” for the direction interest rates are headed, have caused a two-year cap on a $25 million loan at a 4 percent strike rate to rise to $569,000 today compared with $97,000 a year ago, according to Chatham data.

“The higher the forward-looking expectations are for SOFR, the more expensive the cap is going to be,” Moore said. “It’s essentially an insurance policy on rates.”

With no sign of the Fed lowering rates anytime soon, some sponsors with struggling properties may be forced to sell their assets rather than take the financial hit of buying a new interest rate cap for a refinance loan.

Michael Gigliotti, co-head of brokerage firm JLL’s New York City office, said property owners are now faced with limited options when it comes to expiring interest rate caps — unlike during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, when lenders would often agree to loan extensions. All possible paths are pricey, whether it’s purchasing a new cap, paying down the loan, or refinancing with elevated borrowing costs. That last option might spur more sponsors to sell at a loss.

“It’s the margin call of real estate and there’s no avoiding it,” Gigliotti said. “The cap is a financial instrument that sits in between the lender and the borrower, and you have to deal with it in one way or the other.”

The prospect of borrowers selling their assets for a loss or handing the keys back to their lenders presents opportunities for brokers since it will result in increased transaction activity. JLL has been proactively out in front of the issue by helping clients with interest rate management through its partner company, Kensington Capital Advisors, to find solutions for caps that have term remaining, Gigliotti said.

The pressure due to higher interest rate cap costs extends to lenders, too.

“As interest rate caps expire and borrowers are asked to reach into their pockets to buy a new cap, that poses a lot of challenges between borrowers and lenders, and, if that ignites some sort of a default scenario, then that has ramifications for both that are challenging at the moment,” said Josh Zegen, managing principal at Madison Realty Capital. “You’re seeing a lot of these situations where the cap is up, a borrower is asked to renew, and the renewal is costing a lot more than the cost of carry and the cost of purchasing a cap.”

Increased borrowing costs are already weighing heavily on CRE lending, with origination volume 54 percent lower in the fourth quarter of 2022 compared with the third quarter, according to the Mortgage Bankers Association. The real estate finance industry trade group predicts a 15 percent annual drop in CRE lending in 2023, but projects a 32 percent bounceback in 2024, when market participants gain more clarity on the new normal of interest rates and valuations.

While increased borrowing costs overall are creating near-term barriers for financing deals, there is potential for expiring interest rate caps to spur more transaction and loan sales volume from sponsors deciding they need to sell due to high carrying costs. Zegen noted that many deals before were “masked” by an “artificial” interest rate that borrowers were paying because of the cap.

“People have to either put up more money to hold, or if they’re levered up then they’re going to have to do something,” Zegen said. “It’s preserving capital mode versus making money, and I think there’s a lot of borrowers faced with that problem at the moment.”

Warren de Haan, managing partner and co-CEO of Acore Capital, said the lender’s 35-person asset management team provides valuable research in determining whether a sponsor can handle increased costs from an expiring cap or higher borrowing for a refi loan. He noted that in some cases a new interest rate cap may not be necessary right away if sponsors demonstrate strong debt service coverage ratios.

“When a borrower runs up against a cap issue, our job is not to just say no. Our job is to work with the borrower to figure out how we can be commercial about what to do,” de Haan said. “To the extent that the loan is low leverage, the borrower is liquid and we like the credit fundamentals of the loan, we could allow for some of the interest to [payment-in-kind] for a period to minimize the cost or provide flexibility around the interest rate cap.”

While the interest rate cap environment is causing stress for some borrowers, other sponsors are positioned to take advantage of the dislocation in the market.

Harbor Group International (HGI), for example, acquired three multifamily assets in San Antonio, Texas, with 828 total units from an undisclosed owner who was prompted to sell because of an expiring cap. Richard Litton, president of HGI, expects many more buying opportunities like this to pop up this year.

“If the owners don’t have the ability to call capital from their investors and if they haven’t preserved liquidity or planned for some of these costs, it will have a real dramatic impact,” Litton said. “If you have an asset in a big fund and there’s lots of other cash-flow support from the fund for the asset, that might be more manageable, but a lot of real estate is single-asset partnerships or LLCs that can’t access other sources of cash-flow support.”

In anticipation of the rising interest rate environment, Litton said HGI last year was proactive in selling off a number of its properties with floating-rate debt. Fixed-rate debt now makes up 71 percent of HGI’s portfolio, compared with 60 percent in early 2022, he said.

Ronald Dickerman, founder and president of real estate private equity firm Madison International Realty, said Madison has taken a “very conservative” approach to borrowing, with 98 percent of its portfolio in fixed-rate debt positions, and therefore is well set up for near-term interest rate challenges. Dickerman noted, though, that increased interest rate cap costs will be an issue going forward as Madison seeks floating-rate loans depending on borrowing conditions. The increased costs also complicate future transactions.

“The big elephant in the room is cap rate expansion and what it’s doing to valuations,” Dickerman said. “I have the view that there is no such thing as a [4 percent] cap anymore, and that cap rates have really settled into the 5s. And, just when you think you’re getting out of the woods, you start seeing more volatility.”

Andrew Coen can be reached at acoen@commercialobserver.com