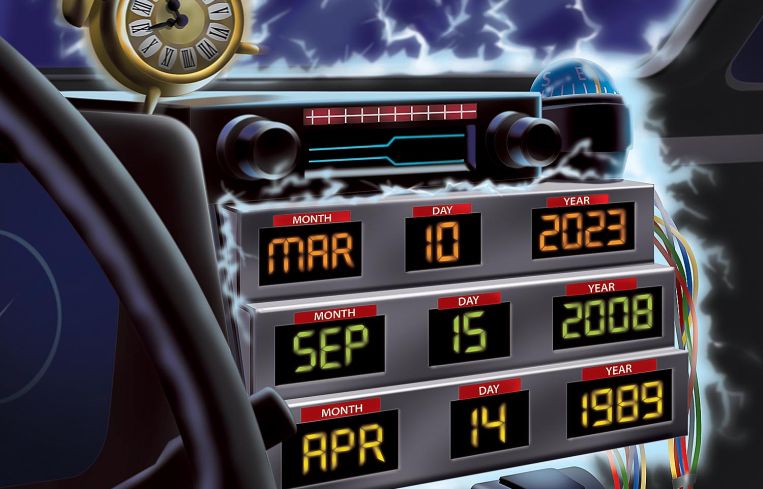

Forget Comparisons to 2008. Today’s Banking Crisis Looks Like the S&L Crash.

Three decades ago, the Fed also jacked rates through a seemingly interminable market decline

By Brian Pascus March 27, 2023 12:16 pm

reprints

Stop if you heard this one before: Amid bank failures and depositor concerns, with headlines warning the threat of financial contagion and businesses bracing for a recession, the most powerful central bank in the world decides to … raise interest rates?

If the kicker seems strange — and so unlike how the regulators responded to the 2008 Global Financial Crisis (GFC), when the Federal Reserve cut its benchmark rate from 4.2 percent in December 2007 to 0.16 percent by December 2008 — it’s because many commercial real estate professionals expected a different decision from Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell on March 22.

Rather than chart a familiar course, and one taken by his predecessors at the Eccles Building during the unprecedented period of quantitative easing in the 10 years following summer 2007, Powell chose to bring the effective rate to nearly 5 percent. And he signaled more rate hikes are on the horizon to fight the high prices brought on by inflation.

The central bank’s decision to increase interest rates by a quarter point on March 22 — the seventh straight rate increase in the last 12 months — came at a particularly precarious moment for the economy: Not only have two U.S. regional banks recently failed, but $936 billion in CRE and multifamily debt is due to mature in 2023 and 2024, with more than half of the debt provided by commercial banks.

“Because of the very rapid rise in interest rates, there is growing concern about what options will be left for borrowers, or for the institutions who hold these loans, as these loans mature,” wrote Jeffrey DeBoer, president and CEO of The Real Estate Roundtable, an industry lobbying group, in a March 17 letter addressed to Powell and other regulators. “Immediate value adjustments to reflect the new interest rate environment would lead to potentially significant value declines, requiring unprecedented additional equity investments or capital reserves.”

Given that Powell only days later seemingly ignored DeBoer’s warning that higher interest rates have “negative results” on CRE debt, and more broadly, CRE properties, it begs the question: Is commercial real estate being left hung out to dry?

George M. Klett, who led Signature Bank’s commercial real estate division from 2007 to 2018 before retiring five years ago, believes so.

Klett lamented the impact higher interest rates will have on all aspects of CRE and said regulators only helped hasten the collapse of Signature Bank, which was seized by the federal government March 12. With rates at nearly 5 percent, the increased cost of development will slow down the number of new projects, and the inability of developers to refinance loans at similar rates as they had just 18 months ago is likely to cause many projects to go belly up, Klett explained.

“I’m not a rocket scientist, I’ve been doing real estate for 30 years, but when you [raise interest rates] in such a short period of time — and do it so dramatically — it will have a terrible effect on business,” Klett said. “This craziness in increasing the rates will affect commercial real estate and residential real estate and all other businesses.”

The concerns surrounding CRE are manifold: Many office buildings have lost value following the pandemic, which exposed the ubiquity of hybrid work, putting loans backed by office properties at risk; increased interest rates have upended property valuations, impacting cash flows and refinances alike; retail remains imperiled due to the growth of Amazon and other industrial storage centers that can ship products within days, if not hours; multifamily properties are harder to finance in cities like New York and Los Angeles without pro-development tax breaks previously supported by local legislatures.

Perhaps most worrisome for developers and executives alike are the novel dynamics at play during this critical moment.

Toby Cobb, co-founder and managing partner of 3650 REIT, an alternative lender, has more than 30 years of experience in commercial real estate. Cobb described construction and overbuilding as the vast majority of the challenges executives faced in previous real estate crises, where there were too many square feet of assets compared to the number of people who needed them.

“Most, if not all, of the real estate crises in our lifetime were supply-and-demand dynamics,” Cobb said. “That’s been the vast majority of our problems historically, including the 1990s, certainly post-GFC.

“If there was truly a supply-and-demand imbalance, then time and capital could solve the problem: growth, need for more space, passage of time, fill up the space,” Cobb added. “As long as you had the capital to wait out the period for growth to catch up to space needs, then you could fill the asset.”

Cobb now fears something far different — and more difficult — is at play this time around, one that CRE financiers and their federal regulators might have solved in the past through big capital investments and a bit of creative destruction.

“We fear that this go-around has a functional obsolescence component to it that makes it far more dastardly,” he said. “In the sense that big capital swaths coming in and buying up a pool of defaulted credits would be an incredibly bad strategy. [If you do that] you’re hosed.”

If this sounds like the industry is entering a death spiral that resembles the 2008 crash, there are economists who would tell you the landscape is nowhere near as dangerous.

“We’re in a situation now that’s very different,” said Joel Naroff, president of Naroff Economics and a former chief economist for several regional banks, including TD Bank. “The crisis in ’07, ’08, ’09 was due to a housing bubble and financial engineering of products that essentially allowed people to get mortgages they couldn’t afford. [Back then] you had financial machinations, financial engineering, stupid regulators and out-and-out fraud.”

Other economists agreed that while the landscape for commercial real estate is presently troubling, it’s not at the same disturbing point as the GFC.

“2007-2008 was a full-blown crisis, not just in the real estate sector but its relationships to banks and the economy and economic growth,” said Joseph Mason, professor of finance at Louisiana State University, who noted that lending, construction, land investment, sales and building terms were all at risk from the banking contagion of 15 years ago.

“A big chunk of the U.S. economy was imperiled, and that’s clearly a situation when you want to lower rates and make borrowing easier to tide people over,” Mason added.

Naroff described the present environment, especially the sudden rise in interest rates, as resembling the savings-and-loan (S&L) financial crisis in the late 1980s that helped set off the recession in the early 1990s.

Prior to that somewhat forgotten financial crisis, many savings-and-loans institutions borrowed short through deposits and lent long on maturities, mostly mortgages, Naroff explained, and the institutions were protected by regulations that didn’t require they pay market prices or rates for deposits. This allowed them to accrue unlimited deposits at low rates even as they continued to lend out at higher rates to customers buying home mortgages.

Not only did the financial system evolve by the end of the 1980s — money market accounts and certificates of deposit (CDs) appeared on the scene, rending many S&Ls relics of the past — but the Fed raised the federal funds rate from 6.58 percent in March 1988 to 9.81 percent by May 1989. With the abrupt jump in interest rates, S&Ls had to pay up in the market on their long-term loans, as large portions of their asset bases were fixed-rate mortgages, Naroff explained.

“You can see how the world changed on them,” he said. “A lot of them were the walking dead until they were dead. Once you had a spike in interest rates, there was no way they could cover it.”

If this sounds familiar, it’s because a nearly identical situation happened in March at Silicon Valley Bank.

The now-deceased California-based regional lender held a huge portion of its assets in amortized totals of held-to-maturity (HTM) securities, debt securities purchased with the intention of being held long term, like 10-year or 30-year Treasury bonds. These long-term securities fell in value once interest rates rose last year, forcing Silicon Valley Bank to sell them at a loss of nearly $2 billion and scaring depositors enough to spawn a classic run on the bank.

The upheaval has continued through the month. First Citizens Bank acquired the remnants of Silicon Valley Bank for $72 billion on March 27, a deal that included a $16.5 billion discount and transfer of deposits worth up to $56 billion.

“It’s similar to the S&L crisis in structure, in that they went out on the curve, they bought longer-term assets and they were still paying short-term money,” Naroff said.

But as the dust settles over a regional banking crisis that remains a threat to the overall financial system, some CRE professionals don’t believe the landscape is altogether unfavorable to their industry.

“I wouldn’t say commercial real estate is being hung out to dry, but I do think the interest rate hike does have an adverse impact on real estate,” said Eric Orenstein, attorney at Rosenberg & Estis, a law firm that specializes in real estate transactions.

“But you could look at it from the flip side, you can say the market was completely out of whack, the values were astronomical and not in line with what realistic values should have been,” Orenstein continued. “So maybe this is pushing us toward a market reset that ultimately could be a net positive for the real estate industry.”

Orenstein noted that those investing in the multifamily space could benefit from the increased interest rates because many loans originated through Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac federal programs carry assumption provisions that allow the new buyer of multifamily properties to assume an existing loan without having to refinance.

“The advantage to that is if you closed the loan three years ago, it’s a much lower rate, so the assumption is worth something and the seller can charge a premium,” Orenstein explained.

In the same manner, Nitin Chexal, co-founder and CEO at real estate investment firm Palladius Capital, doesn’t define the present situation as anything like a mass contagion through the financial system, though he did conclude post-COVID CRE could be inaugurating a world of haves and have-nots, particularly office, retail and full-service hospitality in both secondary and tertiary markets.

“Certain asset classes like offices are structurally just impaired on a go-forward basis because the utilization of that real estate has changed dramatically since COVID happened, and the same is true of regional malls,” Chexal said. “As you think about real estate, and debate what the impairment-in-value is as a result of rising interest rates, a lot of what’s going to happen is a function of utilization.”

Conversely, Chexal said that spaces like industrial — specifically multi tenant industrial focused on last-mile delivery — and student housing in states likes Texas, Florida, Georgia and the Carolinas are seeing their values and NOI growth outpace an expansion of cap rates because vacancy is so tight and demand is so strong in those areas.

Regardless of whether CRE enters an intractable decline, or encounters something more like a cyclical market correction, the shift is most likely due to the economic upheaval brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic and the various resources used to control it.

Professor Mason noted that throughout U.S. history a recession usually follows war, due to the ramp-up of production and subsequent tapering down of activity during peacetime. He said the economic expenditures that were required to fight the war on COVID shouldn’t be considered any different, especially when looking at the long-term implications for CRE.

“When it comes to [CRE] you have a similar effect. There was decreased demand for commercial real estate and an ability to tide this over for a while, but one can imagine now the hen’s coming home to roost,” Mason said. “Maybe this is it. Commercial real estate might just be at the heart of a broad-based economic adjustment overall.”

Brian Pascus can be reached at bpascus@commercialobserver.com