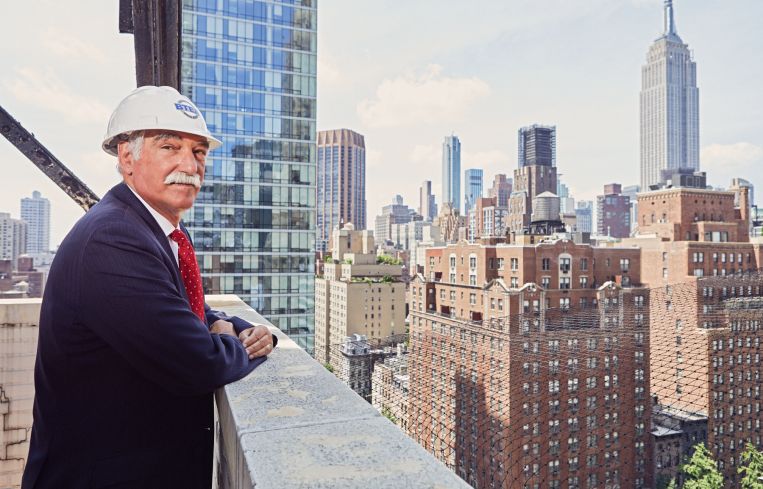

Lou Coletti, Head of NY’s Building Trades Employers’ Association, Talks Construction

The president and CEO of the powerful contractors union sees challenges in obsolete office space, construction insurance costs and the death of 421a

By David M. Levitt June 20, 2022 7:00 am

reprints

With so much riding on the future of New York’s office market — from the landlords to the stores to the restaurants to neighborhoods from the Plaza District to FiDi — one aspect not getting enough attention is the construction trade.

If companies up to their necks in remote workers find themselves not needing as many square feet of office space, is that going to translate into fewer new office buildings? How might an industry that just a few years ago seemed to have it made in the shade — between the jumbos rising in Hudson Yards and similarly sized skyscrapers expected in Midtown East — survive a potential contraction in demand?

These are not academic questions for Lou Coletti, president and CEO of the New York chapter of the Building Trades Employers’ Association since 1997. As the boss of the umbrella organization for the city’s unionized construction contractors and subcontractors, Coletti is a proxy voice for the 125,000 men and women who work for those firms. Historically, the BTEA and its leaders have been among the most powerful and influential in New York City. If demand for new construction does drop, that could change fast.

In late May, Commercial Observer interviewed Coletti by phone about the many questions for the construction industry arising out of the pandemic. His answers have been edited for length and clarity.

Commercial Observer: Federal labor numbers show the construction industry employee number in the New York area hovering around 180,000 when pre-COVID it was around 210,000. What do you see that as a reflection of?

Lou Coletti: I have to break the construction workforce into two sets. One is the union workforce and one is the nonunion workforce. What I am hearing is that in the nonunion sector, they’re having a very difficult time getting people to work. They’re having labor shortages. We are not experiencing that in the union labor workforce.

So what exactly is happening? Why is the nonunion workforce being depleted like this?

On our side, we have institutional mechanisms for recruiting new members through our apprenticeship program, and they’re fairly strong. Over the course of years, they are recruiting personnel, and all these training programs are paid for by BTEA contractors and managed by labor management trustees.

The nonunion workforce really does not have any institutional mechanism to recruit workers. Typically, nonunion workers are paid significantly less, don’t have the kinds of medical coverage and fringe benefit packages. And so, therefore, are saying, “If you’re not going to pay me more money, or if I’m not going to be covered in a COVID environment and not be paid if I get COVID, then I’m not going to work for you.”

We always have a pool of people that are ready and available to be put to work if a particular job site has an outbreak of COVID. We have people to replace them.

Do some of these workers come from places outside the New York area?

They come from New York. They come from New Jersey. They come from Long Island. There’s no residency requirement to get into an apprenticeship program.

In the last 10 years, we created three mechanisms: construction skills, which focuses on New York City high school graduates; “Helmets to Hard Hats,” which recruits veterans; and nontraditional employment for women. Those mechanisms focus on New York City residents, and allow them to jump to the top of the list when we have vacancies in the apprenticeship program.

Give me your thoughts about the actual or potential decline in the demand for offices, as a result of what we have been seeing in COVID, and the use of laptop computers and a more mobile workforce. Is this going to translate into fewer building projects and therefore less demand for your workers?

COVID has changed the face of the New York City economy. Will there still be construction of new commercial buildings? Yes. New York City will remain as the financial capital of the world. There will be new buildings going up; there may not be as many of them.

But with the new technology in demand, much of the older office space will be very expensive and difficult to renovate — which is why we have supported the Real Estate Board of New York’s proposal to turn a lot of that space into residential space.

I still believe New York City will continue to grow on the commercial side. But I also believe that one of the busier markets that we’re seeing as a result of what we’re talking about is the interior renovation market. Those employers, those companies who have long-term leases and whose workers are not coming in five days a week, they are adjusting their offices as we speak. So there are adjustments being made in existing commercial space to reflect the reality that fewer and fewer people will be coming in five days a week.

There’s still a very high demand for residential projects. Although I have to tell you, if the legislature does not reauthorize 421a, that’s going to put a significant crimp in the residential construction that we so desperately need.

It seems that what is happening, particularly here in New York, is that companies still want to have that space that carries their corporate message, a corporate culture, a place where people can collaborate. But they may not need it five days a week. And they don’t want to be commuting the long distances they have been commuting. What’d you think?

I believe that we will have a new normal. And that new normal will be defined as perhaps a smaller footprint, but a footprint that has all the technological bells and whistles that you need to compete in today’s new world. And there are some older buildings for which that would be tremendously expensive, and there will be a demand for newer space. The question is what’s the size and scope of that demand?

So, asked another way, are we going to see more 1 Vanderbilts? And what is going to happen to all those wedding-cake buildings built before World War II?

You will continue to see buildings like 1 Vanderbilt, maybe not as many. I think we need some changes in public policy to incentivize developers for some of those older spaces, to enable them to convert them to residential space. Their space is just not going to accommodate itself to the new technological demand of the commercial world. And the price will be just too expensive, and people will gravitate more towards that newer space.

What impact do you expect, if any, from the demise of 421a? Do you think we’re on the eve of something new that is going to incentivize residential development? Or is 421a going away and we’re going to be sorry it did?

If 421a is not extended, that will have a devastating impact on the ability to meet the demand for residential. Now, I also believe that there are some other things that go along with 421a.

One is our public policy that will make it easier for private developers to convert commercial space that is basically unusable in today’s marketplace to residential. So this all has to be linked. And we also have to find some other ways to reduce the costs of construction in New York City. And one of the main challenges in that is the cost of insurance. With the Section 240 Scaffold Law [which mandates strict standards to protect workers who rely on scaffolds], New York state has the highest insurance rates of any state in the nation.

The cost of insurance in New York state is about $41 per square foot. Compare that to about $5 a square foot for building a new building in New Jersey, $3 a square foot in Connecticut. And you can see why there are so many offices that are deciding they’re just going to leave New York. And that’s with only maybe two insurers still willing to write insurance in New York. It just becomes easier to build somewhere else. That is what I believe is the major threat to the city’s economic viability.

So does the situation offer any hope? Is there going to be a successor to 421a? Or is it just going to peter out?

I saw a quote from the governor today that said that if 421a is not reauthorized in this legislative session, it will be a major priority in the next session. And it has to be a major priority. The combination of no incentive and the high cost of construction will have a very negative impact on residential construction in New York City.

I want to change the subject a little bit. Women and minorities have been trying to push into this industry for generations, but some numbers show they’ve been disproportionately hurt by the pandemic. What are your thoughts?

Let me take two perspectives. One is the minority- and women-owned contractors. And then the second piece is the actual construction workforce. On the minority- and women-owned contractors side of the discussion, we have more MWBE than any other contractor association in the state of New York.

Have they been disproportionately affected? Yes. Many of them do public work. And the development process, both public and private work, is in major need of reform.

The largest challenges that they face are the cost of insurance, which they either cannot get or cannot afford. The mayor is addressing this: I’m a member of the mayor’s task force, the Capital Process Reform Task Force. We are looking at all those processes.

Also part of that is how do we consolidate all the required permits for private projects, so we can get those projects moving faster. Those elements are absolutely critical to the success of MWBE contractors in the city.

You said there was another side.

On the workforce side, it’s not a very well-known fact, but 55 percent of the 100,000 building trade union members are minorities and women. We just did a report that documented that: 30.5 percent of that 100,000 are Latino, 21.2 percent are Black, and 3 percent are women. And the key to that growing diversity are the three programs I mentioned to you before. The nonunion sector has none of those things that we’re talking about.

Let’s talk a little bit about transit projects. A lot of folks blame unions for them being so expensive, and similar projects in other countries seem cheaper. Is that an illusion? What can be done to make something like the extension of the Second Avenue Subway more cost effective? And do you think the changes brought about by technology and COVID bode ill for such projects?

That’s an illusion, and I’ll tell you why. No. 1, on all those projects you must pay your workers the prevailing wage. That’s the law. Whether you’re union or nonunion, everybody’s paid the same. That’s just a myth that continues to get perpetrated.

A way that costs can be reduced, and I hate to keep going back to it, it’s the cost of insurance. Because that affects both a union and nonunion contractor.

A lot of times, the general public really lacks the understanding of how complicated these types of projects are. When you’re digging underground, you very often don’t know what you’re going to find until you start construction.

Are you concerned about demand for mass transit declining because fewer people want to commute anymore?

I really don’t see a negative impact. And I’ll tell you why. Because we’re still catching up for our lack of investment over the past 20 years, much of this work still needs to be done. Even if there’s a reduced volume of people, I don’t believe that the volume will be reduced in any significant manner because I still think the very important part of work life will be some level of people commuting into the city. Three days a week, maybe it won’t be five. But they’re always going to favor mass transit over commuting by car because the cost of gas is astronomical.

I see more of an issue in cleaning up the crime and the homelessness on the subways.