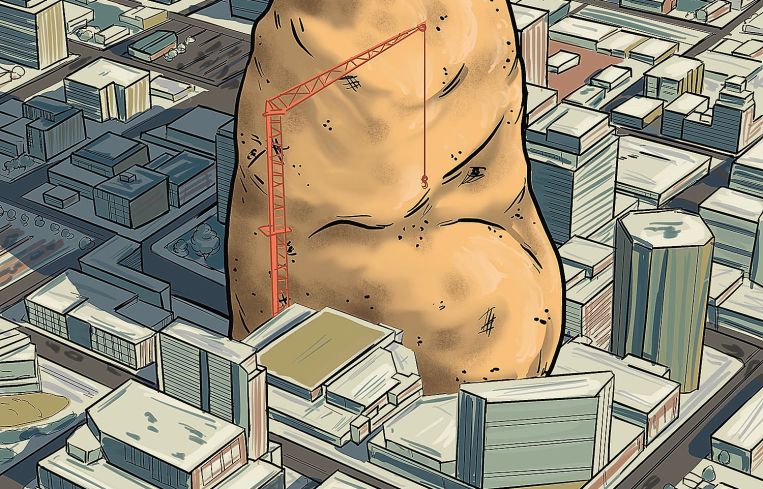

The Skyscrapers of Boise

America's smaller cities are seeing a boomlet in vertical construction — 20 stories, oh my!

By Patrick Sisson June 21, 2022 6:00 am

reprints

Those who haven’t visited downtown Boise in the last couple of years might hear the term “high-rise living in Idaho” and conjure visions of mountaintop cabins or loft apartments crowning barns.

But that’s a sad stereotype of a dynamic, fast-growing city that’s seeing a significant shift in its skyline. Proposals for a 27-story luxury apartment building by local firm Oppenheimer Development and a 19-story apartment tower called Ovation would dwarf the city’s tallest existing structure, the 18-story Zions Bank headquarters

So far, that’s just speculation. Despite months of talk, neither of these projects has moved past the proposal stage, said Don Day, editor of BoiseDev, the city’s go-to real estate site, and there’s not a crane in sight.

But come back down to earth, and adjust your gaze to the six-to-eight-story range, and it’s clear a more vibrant, though not quite as vertical, series of apartment towers has brought big changes to Boise’s downtown. In recent years, as the city’s population has boomed, growing 14.6 percent, or by about 30,000, between 2010 and 2020, the shift has been unmistakable. Eight- and nine-story mid-rises have supplanted one- and two-story buildings, and single-family homes have been knocked down to make way for multifamily buildings.

“We are seeing an evolution towards downtown apartments here,” Day said. “We’re seeing a bunch of it, with new inventory coming online and in various development stages. It’s the next era of Boise’s downtown, which is a return to living here.”

Boise’s residential development boom by itself isn’t news, especially to potential homebuyers in Treasure Valley who have seen home prices skyrocket for years as relocations and rising home prices push developers to break ground in more and more nearby suburbs. But the push to go more vertical, despite slowdowns in retail and office markets, is poised to shift the skyline in similar smaller cities and suburbs across the country.

Multifamily construction in small metros of 250,000 or less represented 23 percent of all such construction nationally in the fourth quarter of 2021, according to the NAHB Home Building Geography Index, a 43.5 percent annual jump. Suburbs of large metros saw a quarter of multifamily construction nationally over that time period, a 22 percent boost from 2020.

“It’ll be interesting to see what those kinds of projects do to the market,” said Jeremiah Jolicoeur, managing director for the Pacific Northwest for Alliance Residential, which is planning an eight-story podium project in downtown Boise called Broadstone Saratoga. Years ago, when Phoenix-based Alliance entered the market, urban infill of that height wasn’t on the radar. But demand has shifted.

“Many people came to Boise from areas with infill, and there are a lot of young folks who seem to like it downtown and don’t want to leave,” Jolicoeur added. “You’ve created demand for urban infill housing in Boise. It’s everything we wish Portland and Seattle could still be: safe and clean and growing.”

Secular trends, such as the growth of the suburbs and midsize cities, especially due to skyrocketing home prices, have propelled this shift. It’s been accelerated by pandemic-era trends like remote work relocation, the multifamily boom and rapidly rising rents, which have created more and more opportunity for mid-rise structures in areas where anything more than a few stories tall would have been a rarity just years ago. So-called “Zoom towns” full of remote workers have seen an investment boom in recent years.

“There are definitely markets today where we wouldn’t have considered the mid-rise product that we are today,” said Chris Fletcher, executive vice president of development at Cortland, which is active in 11 states, especially in the Sun Belt and Mountain West.

A number of Sun Belt metros have seen explosive growth in deals and development following this high population growth. These include Jacksonville, Fla., and growing cities in Arizona and Texas, where rising housing prices have bid up rents across the board. The housing shortages and demographic trends pushing this growth show little sign of slowing.

“During COVID, a lot of the amenities in those higher-cost cities came from getting out and about,” said Fletcher. “Well, you lost those, so people felt like ‘What am I spending all this money on?’ ”

In Tacoma, Wash., the Hailey Apartments, a 186-unit, five-story project by L.A.-based Cypress Equity Investments, with rents starting at roughly $1,600 a month for a studio, is expected to fully lease up by the end of 2022, roughly a year after it opened. Its location on Tacoma Avenue, formerly a parking lot, has become a nexus for similar projects in the fast-growing Pacific Northwest market, which has accelerated since Cypress picked up the site in 2019. Slightly outside the city center, it’s in an area into which the core is expanding. That’s especially true since the beginning of the pandemic, and it’s harder and harder to find enough real estate to do garden-style construction, said Alla Sorochinsky, Cypress Equity Investments’ chief financial officer.

“With people moving out of a more expensive market like Seattle, the population and rent prices can support a more expensive product,” she said.

Other markets with more mid-rise projects include Vancouver, Wash., which is just across the Columbia River from Portland, Ore. Jolicoeur at Alliance said Vancouver’s waterfront especially is seeing more urban development, since it’s more regulatory-friendly and located in an opportunity zone. Cities on the edges of metros — such as the Atlanta suburbs of Duluth and Sugar Hill, where suburban planners and developers have revitalized the downtown areas to make them more vibrant and multi-use — have drawn more interest in multifamily development, to cater to more walkable suburban locations, said Cortland’s Fletcher. More units means more people and more customers for the kind of retail, restaurants and entertainment options many urban transplants want.

But finding sites can be especially challenging in these areas, said Sorochinsky. A site needs to be close to retail, and the increase in interest rates and other economic pressures have made it more difficult to find plots that pencil out. (Comparing prices by market can be complicated, said Jolicoeur; material prices remain the same everywhere, but fewer regulations, seismic codes and union presence make it cheaper in, say, Boise than Seattle.) Most garden-style multifamily projects require 15-acre lots, Fletcher added, and with fewer and fewer of those available as these smaller cities and suburbs fill in, the only solution is to go up.

“To build that podium product, you need to be a little closer to urban infill,” said Sorochinsky. Projects need comps, high rents, significant population figures and other baseline data to support taller, denser construction. “We’re seeing the money go towards the suburban product. We’re following the jobs; the population is moving into these areas.”

Podium and higher-density projects often need to be near more transit-oriented areas, too. Just south of Seattle, in Tukwila, Wash., in a neighborhood called Southcenter, Alliance is planning its third high-rise (for the area), a six-story, 285-unit multifamily podium project, helped in part by good transit options and the lack of affordable housing requirements. A lack of NIMBYism also helps, noted Fletcher; some suburbs have, in effect, outlawed multifamily, making it even more necessary to pick up smaller infill parcels for mid-rise projects.

Parking, as always, plays a big role. Requirements for structured parking often push projects to need Class A rents. Similarly, regulations as a whole also play a big role, especially zoning and taxes. That’s why Jolicoeur says Vancouver, Wash., is seeing more developer interest. Bigger cities’ code and design reviews can kill so many unsubsidized affordable housing projects.

“If I can develop in a more business-friendly environment like Boise, like Spokane, Vancouver, who knows where we go next, why not?” said Jolicoeur. “We’d rather avoid the litany of BS cities like Bellevue and Seattle give you. They’re not mean or nasty about it, but it’s painful, expensive and difficult to get buildings done there. These infill cities have pushed out our workforce.”

While it’s also true that this development tends to favor residential over retail and office, which currently face pandemic-era headwinds, more residential density might just be the magnet that helps commercial districts bounce back over the next few years. BoiseDev’s Day says that downtown Boise still struggles to recover. He predicts over time, though, that new residents will bring back the vibrancy — and perhaps new office and retail projects will follow.

Boise still has plenty of surface parking lots waiting.