Jerome Powell’s Federal Reserve in 2022: What’s Ahead for Commercial Real Estate

The nation’s central bank has basically admitted it was wrong about the risk of long-term inflationary pressure. Commercial real estate is confident the Fed can right the ship.

By Mack Burke December 7, 2021 12:47 pm

reprints

After drawing some ire from Democrats on Capitol Hill — even being referred to as a “dangerous man,” by Sen. Elizabeth Warren — Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell was retained by President Joe Biden last month for another four-year term. It was a sign that the current administration preferred to maintain some continuity within the Fed as the economy continues to rebound from the pandemic, amid a host of challenges.

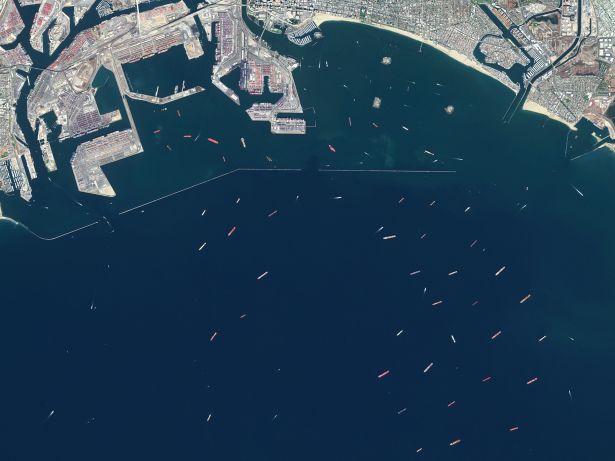

We’re closing in on the two-year mark since the pandemic hit. Labor shortages and global supply chain issues still persist, while demand for goods and shipping levels remain high during the holiday season, which doesn’t bode well for rising prices; production and manufacturing in key Asian supply hubs are sluggish as countries there continue to grapple with the pandemic’s effects; and there’s now a new COVID-19 variant.

The most important concern for Powell’s Fed, by far, is tamping down what has become the highest level of inflation the U.S. has seen in three decades, while not making too swift or too strong a move that would rattle financial markets, slow economic growth, or even push the country into another recession. Looming in the background is the emergence of the omicron variant, which has raised new questions and concerns about its impact on recovering economies and global supply chains.

In the U.S., the stock market has reached new heights, the labor market has been rebounding gradually, and certain industries — like the more recession-resistant commercial real estate sector — have expanded. But both input and output prices continue to soar, impacting both businesses and consumers.

Recent research from the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland found that about 80 percent of firms it surveyed indicated that their operating costs had climbed in the last couple of months, and about 65 percent of those surveyed said that they had compensated for that by raising prices. Many of the businesses also said they are expecting supply-chain issues to spill well into 2022. These growing concerns, together with the threat of the omicron variant, have prompted the Fed to at least start discussing deploying its monetary policy tools more quickly to stabilize the economy.

“The inflation shock has been much more intense and has lasted a lot longer than anybody really expected, to be honest,” Brian Coulton, Fitch Ratings’ chief economist, said, adding that it surpassed his expectations from the summer. “The nature of the shock and the surprise we’ve had has really started to change the debate in the FOMC about the outlook for rates.”

Earlier this month, members of the FOMC, or Federal Open Markets Committee — a panel within the Fed system responsible for exploring, directing and implementing monetary policy decisions — really began to sound the alarm on inflation, calling for a faster rollback of the Fed’s $120 billion-per-month bond buying program and stimulus measures so that it can begin raising interest rates to combat rising prices at a time when the U.S.’ gross domestic product has surpassed pre-pandemic levels.

The Fed started the tapering last month, cutting its monthly purchases of Treasury and mortgage bonds by $15 billion. But, on Nov. 30, in the wake of the omicron news, Powell said the central bank would debate a speedier tapering schedule when it convenes in mid-December.

“I, frankly, don’t see the need to be buying [mortgage-backed securities],” said Lisa Pendergast, the executive director of the Commercial Real Estate Finance Council (CREFC), a trade organization that advocates on behalf of the $5 trillion commercial real estate finance sector. CREFC was very active at the onset of the pandemic, working with the government and the Fed to establish targeted support for the commercial property sector.

“The new variant raises more questions,” Pendergast added. “The Fed is shadow boxing with something that comes and goes in terms of its veracity. Overall, I think they’ve done a good job, but now, at [6 to 8 percent inflation] you’re supposed to take note.”

At $15 billion per month, the Fed’s asset purchases would expire in June 2022, and, at that pace, Coulton doesn’t expect the central bank to start raising interest rates until the latter half of 2022. Doubling the drawdown of its monthly asset purchases would see the stimulus fizzle out by about March.

“It would be quite odd for the Fed to raise interest rates while they are still purchasing assets,” Coulton said. “It would be hard to explain to the markets what they were trying to do there. Effectively, they’d still be easing by printing more money and buying more assets, despite the policy loosening, but, if they’re raising rates at the same time, it’d raise questions.”

Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta President Raphael Bostic and James Bullard, his counterpart in St. Louis — both FOMC members — expressed concern last week in public comments about rising inflation stifling ongoing economic growth in a tight labor market. Both insisted that the time is right for the central bank to move faster to reach a point where it can raise rates.

Over the last several months, as inflation has continued to climb, the Fed has deployed a patient approach, one that many economists and financial professionals, including those that spoke to Commercial Observer, have said was to make up for the country running below its 2 percent target inflation level in past years.

U.S. annual inflation ran below 2 percent from 2012 to 2015, hitting a bottom of 0.7 percent in 2015, according to data from the U.S. Labor Department’s Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). From 2016 through 2019, it was stable at around 2 percent, falling to 1.4 percent in 2020, according to BLS data. But, through Nov. 10, 2021, when the most recent data was made available, annual inflation sits at 6.2 percent, having climbed steadily every month since January. The next round of inflation data will be released on Dec. 10, ahead of the Fed’s mid-December meeting.

“Personally, to have the Fed be as sanguine as they are [about inflation], or at least as much as they suggested they are — saying it’s transitory — it unnerves me every single day,” Pendergast said. “And, from a commercial real estate perspective, we know lower mortgage rates and lower cap rates are all positive for [the sector]. Those low rates were extremely helpful in allowing anyone that had a loan maturing or a loan they thought they could refinance at a low rate to do so in an environment where there was great uncertainty as to demand for real estate.”

After previous comments made throughout the year about rising inflation being a temporary hurdle for the economy, Powell shifted gears on Nov. 30, saying that he no longer believed that the term “transitory” should be used to describe inflation in the U.S.

On Dec. 2, Fed Governor Randal Quarles, who announced his resignation from the central bank in early November and is set to leave his post at the end of this month, somewhat mirrored Powell’s concerns and said he was “supportive” of ending asset purchases sooner than initially expected.

Quarles, speaking on an American Enterprise Institute-hosted webinar, said that the central bank had come to realize over the last few weeks that federal stimulus measures that had been implemented over the last two years to help fight COVID-19 had actually worked to amplify demand to levels that could surpass pre-pandemic life. He indicated that before this realization, the Fed had maintained its monetary policy support throughout this year on the back of thinking inflationary pressures were mostly just a result of the economy reopening.

Now, Quarles said, the situation “is not a question of demand at pre-Covid levels and supply taking a while to reach back up to that pre-Covid capacity…we have sustained higher demand.”

He said the Fed needs to act quickly to raise rates in order to “constrain that demand” and allow business to ramp up productivity to be able to match it, balancing the distorted dynamic, which he added was “not really a bottleneck story anymore.”

Coulton at Fitch Ratings said that the pandemic had an interesting impact on demand — something that doesn’t really align with historical spending behavior.

He said the fiscal stimulus from the government, especially in the first half of 2021, was funneled into higher consumer spending on goods at rates so much higher than pre-pandemic levels that it’s “staggering.” U.S. consumer spending on durable goods, in dollar terms, in April 2021 was about 40 percent higher than in December 2019.

“It is really quite striking,” Coulton said. “We’re not talking about a bounceback from the trough in April 2020. It’s just an amazing increase. It’s the fastest growth in durables demand in the post-war period by a long, long way.”

Historically, growth in consumer spending in the U.S. has mostly been driven by services, rather than durable goods. But money that might’ve gone to services was diverted to goods due to pandemic-related shutdowns that stifled spending on services.

Inflation figures for durable goods, excluding energy and services, have been running higher than the overall inflation number at between 7 to 9 percent, according to U.S. Consumer Price Index data.

Coulton said the robust pace of the economic rebound was “completely unexpected,” highlighting the fact that a lot of producers on the supply side that shut down operations for a few months in the spring and summer of 2020 anticipated a much slower recovery.

“I think that has been the source of a lot of these inflation pressures in goods markets,” Coulton added. “We read about supply chain problems, but, actually, if you look at how the supply side is responding, there’s been a lot of output growth, it’s just that it hasn’t been able to keep up with the pace of demand. That mix of the huge stimulus response, together with the stimulus checks sent out to everybody, a lot of it was spent on stuff: autos, TVs and laptops. It’s the fact that that [particular] demand has been so strong that it has been a part of the bottleneck issue.”

The Fed’s tool to slow demand lies in the federal funds rate, and financiers that spoke to CO said they believe financial markets are poised to handle the central bank’s speedier approach to tapering its Treasury and mortgage bond buying and subsequently hiking rates.

“Inflation has always been in the rearview mirror, and now it’s starting to increase because of supply chain issues,” one U.S. commercial real estate banking executive for a global bank told CO on the condition of anonymity. “Inflation is more money chasing fewer goods. The only way to slow it down is to put water on it to lower the temperature; you increase rates so money is less available.”

The Fed dropped its federal funds rate to near zero in response to the pandemic, which caused other short- and long-term interest rates to fall as well, despite the fact that mortgage rates were already quite low before the pandemic — at what was the top of the previous business cycle.

“Interest rates today are the equivalent of someone who’s on a diet feasting on an all-you-can-eat buffet,” the U.S. commercial real estate banking executive said. “It created a distortion where money was cheap, and that encouraged a certain investing behavior.”

The banking executive said his group generally originates floating-rate debt, protecting themselves by installing interest rate caps on their loans that are underwritten to still cover the debt service. For a fixed-rate lender, should rates climb against what’s already been established in a loan that was made in an ultra-low-rate environment, “you have to make sure you can refinance that loan,” the banking executive said. “If you had lent with no margin of safety and rates go up and you have a long-term lease in there, you have a disconnect. The borrower might have to find some gap financing to have the loan paid off. If rates go up, cap rates go up and that decreases values.”

The commercial real estate sector, in general, has been soaring this year, with the debt markets in the third quarter exceeding pre-pandemic volumes, and CREFC’s Pendergast doesn’t envision the sector being thrown off course by Fed action.

“The market loves some sort of quietness, if you will, and [the ability to] properly inform the market as a Federal Reserve governor as to what your intentions are and what might be guiding those intentions,” Pendergast said. “No one wants knee-jerk [reactions].”

Powell’s Fed is facing many more questions than it has answers, right now, but, as the financial sector follows and reacts to its monetary policy, Pendergast said she feels comfortable that Powell, in tandem with U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen, will “land the plane safely.”

Mack Burke can be reached at mburke@commercialobserver.com.