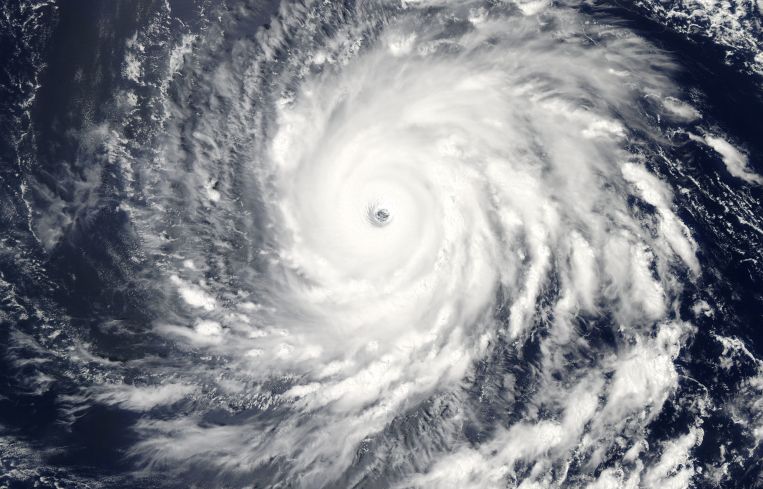

Climate Changed: New York City Grapples With Flooding, Sea Level Rise in Wake of Ida

Hurricane Ida was the latest reminder that New York City remains unprepared for the worst effects of climate change. New plans are afoot though.

By Celia Young November 15, 2021 9:36 am

reprints

The damage from Hurricane Ida in September was hinted at in the images of what the storm left behind. Mud and debris scattered across sidewalks told the story of flooded subway lines and basements, impassable streets, drowning cars and the loss of 18 lives in New York alone.

The storm left behind something more: need. The need not only to repair the damage the storm wrought, but to prevent the horrors of climate change in the now not-so-distant future. While the city has made significant strides to curb greenhouse gas emissions to slow climate change, it’s too late to stop it entirely; and New York City is going to need billions to protect it from the more immediate effects of climate change, like harsher storms, rising seas and flooding.

“They used to call them every-100-year storms,” said Carlo Scissura, president and CEO of the New York Building Congress. “They now happen every few years and New York, like other cities around the globe, is not prepared for these challenges. … Should we have been more prepared for Ida given what we knew? Of course we should have. … The bottom line is we’ve got to act and act now.”

The need to mitigate climate change was clear when Superstorm Sandy tore through the city’s shorelines in 2012, destroying more than 600,000 housing units in New York and New Jersey and turning some neighborhoods into “war zones.” The damage was in the billions — the federal emergency management agency (FEMA) authorized more than $1 billion in assistance for 117,664 people across New York counties, including Queens, the Bronx, Brooklyn and Manhattan. More than $14.1 billion went to public institutions in the state, from governments to nonprofits, to help clear the wreckage, according to FEMA.

FEMA is still tallying the damage from Ida, which caused $16 billion to $24 billion in property damage when it hit the East Coast. As of Oct. 26, 26,752 people have asked FEMA for relief and been granted just under $125 million. Most of the damage was in Brooklyn, Queens, the Bronx and Staten Island, according to a city report.

“I think it’s a wake-up call,” Scissura said. “I think the real estate, the development community, the construction industry [and] the building industry understand that everything we build going forward has to look different than what we’ve built in the past.”

Hurricanes, tropical storms and flooding don’t only damage residential homes, they can cause power outages and flooding in commercial buildings as well. The city is already facing yet another national tragedy — the deadliest pandemic in U.S. history, which has killed more than 730,000 people, overtaking the 1918 flu epidemic in deaths. An environmental catastrophe that harms businesses, public transportation and the city’s Downtown is the last thing New York needs.

To protect themselves and their buildings, property owners have adopted new ways to design towers in order to prevent flood damage to valuable infrastructure like boilers and mechanical systems. By removing equipment from a building’s basement and by building berms — mounded hills that redirect drainage — landlords can protect buildings from flood damage.

“In new buildings on the shorelines you’re seeing a lot of landscape architecture to fight the inevitability of sea level rise in terms of marshes and greens,” said Brendan Schmitt, a partner at Herrick, Feinstein LLP who focuses on construction and real estate development law. “It’s not really planning so much as mitigating.”

But these steps aren’t going to be enough, Schmitt added. While property owners will be incentivized to cut carbon emissions starting in 2024, thanks to a new law, Schmitt said local and federal governments need to step in and encourage change at a broader level to protect the city from the consequences of climate change now.

“No single building owner has any incentive to go do that type of project,” Schmitt said. “These solutions are going to have to be much larger to protect the city and individual property owners against rising seas.”

The city has attempted to ease pressure on drainage systems by seeking out private properties and offering funding and guidance on how to install green infrastructure that will soak up excess water. The New York City Department of Environmental Protection allocated $53 million to the project in June.

On another local level, the City Council passed a bill in early October that requires the Mayor’s Office of Long-Term Planning and Sustainability to develop a plan for climate change every 10 years. If Mayor Bill de Blasio signs the bill, it would require the plans to evaluate weather events, including extreme storms, sea-level rise, flooding, wildfires, extreme heat, precipitation and wind in New York City. The bill would also ask the city to produce recommendations that would protect residents, property and infrastructure.

But until those overarching plans materialize — at earliest Sept. 30, 2022, according to the bill — the city and other local organizations have a hodgepodge basket of initiatives meant to curb climate change and protect New York City’s 500 miles of coastline.

The New York City Economic Development Corporation has worked with the Mayor’s Office of Resiliency to form four coastal projects that cover the Brooklyn and Manhattan bridges, the Seaport, the Financial District, The Battery, and surrounding Battery Park communities. All together, the plans were dubbed the Lower Manhattan Coastal Resiliency (LMCR) project and announced by de Blasio in 2019 with an $800 million allocation, according to the EDC.

Superstorm Sandy inundated many of the areas the LMCR aims to protect, the city found in a study of potential protective measures against sea rise and flooding.

“We were hugely impacted by Hurricane Sandy,” said Josh Nachowitz, senior vice president of economic development for the Alliance for Downtown New York, a business booster group. “I think the overall citywide impacts from both Henri and Ida are obviously really a wake-up call for the entire real estate community. … We certainly saw some wind damage [in Downtown Manhattan], but we were lucky that [Henri, an August storm, and Ida] were not huge events for us specifically.”

The city’s study found that 37 percent of buildings in Lower Manhattan will be at risk from storm surge by the 2050s. By 2100, nearly half of buildings will be at risk from storm surge, and one- fifth of Lower Manhattan’s streets will be at risk of daily flooding as a result of more than six feet of expected sea-level rise. Groundwater table rise would also destabilize about 7 percent of the city’s buildings by 2100, and corrode nearly 40 percent of city underground utilities.

The city identified approximately $500 million worth of climate resilience projects covering 70 percent of Lower Manhattan’s coastline. Some initiatives were permanent infrastructure changes like flood walls underneath the two bridges and rebuilding about the Battery waterfront at a raised height to cope with sea-level rise. Others were intended to be deployed during a storm, like water-filled dams and sand-filled barriers along the Seaport, the area of the Financial District between the Brooklyn Bridge and Battery Park.

But permanent methods to protect the Financial District and the Seaport were harder to find, due to the area being extremely low lying with aging buildings and construction, making it susceptible to flooding. The Seaport is similar to a bowl, where water gets trapped when it enters, according to the EDC’s study. Raising streets could leave buildings inaccessible, flood walls would graze or collide with the FDR Drive, and stop logs — 12-foot tall logs planted in front of buildings — would make pedestrian life uncomfortable, the study concluded.

The mayor announced part of the city’s plan to protect the Financial District and Seaport on Oct. 26 — a $110 million construction project to raise the bulkhead from the Brooklyn Bridge to Pier 17 a few feet and improve drainage in the area. The project would help prevent flooding for the less than a mile stretch of coastline, one step in the billions of dollars needed to protect all of Lower Manhattan, according to the EDC. (The raised bulkhead is not part of a proposed sea wall — a federally led project to build a six-mile, $119 billion barrier against storm surges that was abruptly shelved in February 2020 after then-President Donald Trump mocked it on Twitter.)

New York could also model its approach to climate change after Louisiana, which invested $14.5 billion in federal funding after Hurricane Katrina in levees, pumps, seawalls, floodgates and drainage that protect against storm surge and flooding in New Orleans and surrounding suburbs, the Associated Press reported. The results of this were striking: Katrina killed more than 1,000 people in Louisiana, and, 10 years later, Ida took the lives of only 28.

Numerous officials and executives from the private and public sectors, including from the building trades and the commercial real estate industry, have called for such federal investment in New York, and some semblance of climate change protections might be on the way from Washington. They may just not be the kind that might do the most to physically protect New York.

Lawmakers at the federal level passed an approximately $1 trillion budget package on Nov. 5 that would include spending to address the causes of climate change, namely greenhouse gas emissions, through updating the nation’s electricity grid and funding clean busses and ferries. However, the legislation’s centerpiece at reducing carbon emissions — a $150 billion clean energy program — was rejected by West Virginia Sen. Joe Manchin, the key vote in passing the larger budget package.

The bill provides billions to the Army Corps of Engineers for flood control and river dredging construction projects and $700 million to FEMA to reduce flooding damages. New York City could use some of the funds to improve drainage and plant rain gardens in Harlem and other areas hard-hit by storms, but the city has said it needs billions alone to transform New York’s sewer system to sufficiently and properly drain floodwater.

The Big Apple has gotten federal money for climate infrastructure projects before — the New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) partnered with FEMA to spend more than $2.4 billion to implement storm surge protection for 50-, 60- and 70-year-old public housing buildings and install boilers and generators on rooftops after Superstorm Sandy, the NYCHA said in a report released on Oct. 25. And Gov. Kathy Hochul has indicated that she wants to make “historic investments” in green infrastructure projects.

Regardless of future federal plans, New York City will be dealing with the impacts of climate change in the meantime, no longer having the opportunity to try to avoid them, the Downtown Alliance’s Nachowitz said.

“The time for planning, I think, is past us,” Nachowitz said. “I think you could probably argue that the time for planning passed a while ago. What we really need is to get shovels in the ground and we need real concrete actionable solutions that we can fund realistically, and get moving on these projects.”