Terrorism Risk Insurance Act Remains Long-Lasting Impact of 9/11 on CRE

Legislation propelled industry forward following market pullout in wakes of terrorist attacks

By Andrew Coen September 7, 2021 10:00 am

reprints

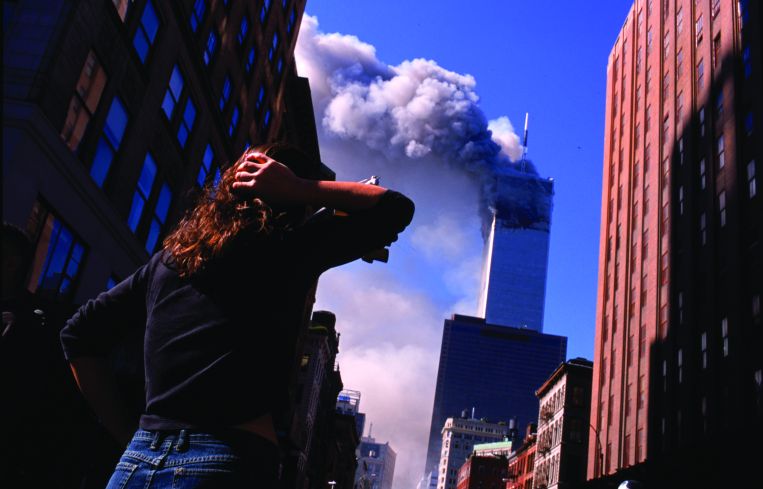

The Terrorism Risk Insurance Act has provided the commercial real estate industry with a crucial backstop against losses suffered from external threats in the nearly two decades since its enactment following the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001.

TRIA, which President George W. Bush first signed into law in November 2002, was designed as a mechanism, whereby the federal government would finance a portion of any property losses resulting from acts of terrorism that caused more than $100 million in damages — up to a cap of $100 billion.

The legislation was initially designed as a three-year program, but has remained in place over the longer term after Congress renewed it four times in 2005, 2007, 2015 and 2019.

The program is not scheduled to expire until Dec. 31, 2027, but commercial real estate experts argue it is important to keep it firmly in place permanently to prevent borrowing costs from spiking and so developers can avoid higher insurance costs.

“Prior to the enactment of TRIA in 2002, it was virtually impossible for commercial real estate policyholders to secure insurance coverage against terrorism risk,” said Chip Rodgers, senior vice president of The Real Estate Roundtable, a lobbying group. “TRIA is essential for commercial real estate as lenders require ‘all risk’ insurance coverage — including terrorism coverage — to cover the risk of loss to the collateral.”

A 2002 Real Estate Roundtable survey indicated that more than $15 billion in real estate-related transactions were stalled or canceled in 17 states, due to a lack of terrorism risk insurance in the 14 months between 9/11 and TRIA’s enactment. Rodgers said these headwinds spurred efforts to craft the TRIA program, so that it maximized private-sector participation, while also providing a federal shield to avoid the real estate maker and overall economy from becoming “paralyzed” after catastrophic events.

In the wake of the 9/11 terrorist attacks, The Real Estate Roundtable organized a coalition of business insurance policyholders, called the Coalition to Insure Against Terrorism, to win passage of TRIA, and the same group has lobbied for each successful reauthorization.

“The availability of a robust, terrorism risk insurance program has been critical to stability in the debt market, not just in the aftermath of 9/11, but in the 20 years that have now passed,” said Sam Chandan, dean of New York University’s Schack Institute of Real Estate.

The vast majority of real estate companies (79 percent) took on terror risk insurance in 2019, up from 68 percent in 2017, according to the latest U.S. Treasury Department report on the effectiveness of TRIA released in June 2020. A 2019 analysis from Marsh McLennan (then known as Marsh & McLennan Companies) — a firm that lost close to 300 employees in the 9/11 attacks — showed that among all businesses, New York City companies were the most frequent buyers of terrorism insurance with an 80 percent take-up rate.

“In the days following the attacks, it became apparent that risk mitigation, risk management and insurance would become critical issues for real estate — given the scale of the attacks — which is when our work on these issues began,” Rodgers said. “Following the tragic attacks of 9/11, reinsurers withdrew from the terrorism risk insurance market, forcing insurance carriers to exclude terrorism coverage from policies — leaving policyholders exposed. This had a profound economic impact on the U.S. economy.”

The TRIA program has also played a large role in enabling commercial real estate originations, according to Daniel Rubock, a senior vice president at Moody’s Investors Service, since most loan documents post-9/11 require some form of insurance against acts of terrorism. Rubock stressed that without TRIA, some commercial real estate lenders would pull out of the market and many borrowers would suffer losses, as insurance companies grapple with elevated risks from potential terrorist acts due to having less access to the capital markets.

“Investors — especially risk-averse, AAA investors in single-borrower deals — could be reluctant to purchase bonds and we, at Moody’s, would have difficulty reaching the full amount of AAA that we would normally give to a deal because of the lack of terrorism insurance,” said Rubock, who co-authored a report on the credit risks of the lack of terrorism insurance six months after the 9/11 attacks on Manhattan’s World Trade Center and the Pentagon in Washington, D.C. “There would be negative credit effects and negative market effects as well.”

Rubock noted that the commercial real estate credit markets were also faced with “unpredictable” credit conditions in the immediate aftermath of 9/11, when reinsurers (insurers of the insurance companies) around the globe withdrew from the market. He said the reality of terrorism being “very inherently unpredictable” meant there was never an avenue for a commercial solution to terrorism insurance, making the federal government’s role pivotal.

Anthony Malkin, chairman, president and CEO at Empire State Realty Trust, said the importance of TRIA goes way beyond office buildings in major cities, since its absence would also be felt by colleges, sports stadiums and hospitals, which have all been identified by federal officials as prime terrorism targets.

Malkin said Congress agreeing to extend TRIA through 2027 two years ago reflected how lawmakers from both political parties recognize the importance of providing property insurance against all risks at commercially reasonable rates, and that ending the program would have a detrimental effect.

“It is not about the level of insurance premiums, it is about the capacity in the markets,” Malkin told Commercial Observer. “The impact on lenders to, owners of, and those who rely on real estate would be devastating.”

The Real Estate Roundtable is already gearing up to engage policymakers about extending TRIA way beyond its expiration date, while also turning its attention to the need for pandemic risk insurance because of the headwinds COVID-19 has brought to the industry.

Rodgers said most business interruption insurance policies fail to cover claims associated with pandemic-related shutdowns mandated by governments, and the roundtable is working with the Business Continuity Coalition to build on some frameworks that have been proposed.

Keeping TRIA afloat for the past 19 years — with the exception of a brief, one-month lapse in early 2015 — has provided continuity to the marketplace, Rodgers said, while businesses can also obtain terrorism insurance coverage without burdening taxpayers.

“Without terrorism insurance coverage, risk is shifted to lenders, shareholders, pensioners and bondholders,” Rodgers said. “As a result, liquidity to the sector would quickly diminish and commercial real estate markets would face a virtual shutdown, as they did after 9/11.”

Andrew Coen can be reached at acoen@commercialobserver.com.