New York Gov. Cuomo’s Crisis Cronies Won’t Be Easy to Dislodge, Either

Some who aided the governor in his attempted coverup hold key policymaking roles — paging Kathy Hochul!

By Aaron Short August 5, 2021 11:25 am

reprints

A recent investigation by the New York attorney general’s office concluded that Gov. Andrew Cuomo sexually harassed at least 11 women who worked with, and for, him — but he didn’t act alone.

The governor relied on a vast network of cronies, planted in key agencies that control the state’s budget, transit and infrastructure priorities, to discredit those making misconduct allegations and threaten others into supporting him, state Attorney General Letitia James’ report found.

Several advisers hold positions with direct control over all state agencies and the $212 billion annual state budget. Others have been appointed by the governor to the board of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority and the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, making decisions that affect not only how millions of people move through the New York region, but also the values of property near different routes and hubs.

Some officials who called for Cuomo to step aside also want everyone that the governor relied on to leave their positions, too.

“Anyone in this administration who participated in bullying and shaming victims, distorting the truth, or engaged in activity to undermine this investigation ought to think long and hard about their involvement,” said Dutchess County Executive Marc Molinaro, a former Republican nominee for governor. “They should step aside.”

On the advice of his aides and loyalists, Cuomo spoke to the public in a televised livestream on Tuesday in the same Emmy-winning format he used to brief New Yorkers about the pandemic’s toll. He brushed back accusations that he hugged, kissed and inappropriately touched multiple staffers, saying, “I do it with everyone,” over a photo montage of him smooching supporters.

This time, his PowerPoint defense didn’t work. Now, the public wants Cuomo out. A Marist Poll conducted that night found that 59 percent of New Yorkers, including 52 percent of Democrats, wanted Cuomo to resign, while only 32 percent believed Cuomo should finish out his term. If he doesn’t quit, 59 percent of New Yorkers said Cuomo should be impeached.

Scores of Democratic lawmakers, including President Joseph Biden and union leaders, called on the governor to resign immediately. If Cuomo doesn’t leave office on his own terms, he faces the possibility of impeachment that could begin as soon as late September.

Cuomo’s legal troubles are far from over. The attorney general’s report concluded that the governor violated state and federal sexual harassment laws, but did not determine whether Cuomo committed any crimes. Albany County District Attorney David Soares announced, though, that he would open a criminal probe based on the report; DAs in Westchester County and Manhattan have made similar moves.

Cuomo may not be the only state official in legal jeopardy. So far, no current or former aides have been implicated for their roles in helping Cuomo stave off the attorney general’s sexual harassment inquiry, but any proven instances of obstruction of justice or witness intimidation could spur criminal charges. And Cuomo’s cronies could potentially have violated state human rights laws if they retaliated against witnesses in defense of the governor, employment attorneys have noted.

“If individuals are actively conspiring with a harasser to effectuate harassment or retaliation, or if individuals are intentionally releasing defamatory or discriminatory information, they could be liable under discrimination law,” said Alice Jump, an employment attorney and partner at Reavis Page Jump.

The attorney general’s 168-page report detailed the brutal, ham-fisted tactics that the governor and his allies used to bury allegations and smear the victims who made them. Time and again, officials failed to report or conduct an investigation following a complaint involving the governor, or had put measures in place to protect the governor instead of the young staffers who experienced his predatory behavior, the report found.

When the allegations became more widely known over the past several months, the governor consulted with current and former aides to plan a counteroffensive. Melissa DeRosa, the most powerful, non-elected official in the state, was cited 187 times in the report. The secretary to the governor was found to have coordinated efforts to harm former aide Lindsey Boylan’s reputation and shut down her allegations by leaking her confidential personnel files to the press. On other occasions, aides who had been harassed felt they could not make complaints about Cuomo’s actions to DeRosa for fear of losing their jobs.

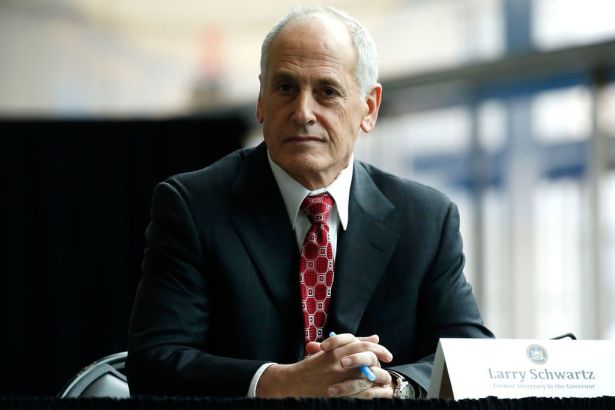

Other longtime former aides — including Linda Lacewell, state Department of Financial Services superintendent and an MTA board member; Larry Schwartz, Cuomo’s former secretary and an MTA board member; and Steve Cohen, chairman of the Gateway Program Development Corporation and a Port Authority board member — advised Cuomo in managing the biggest crisis of his political career. So did several former communications aides as well as the governor’s brother, CNN host Chris Cuomo.

But, they also received “confidential and often privileged information” on state business and made decisions regarding state employees, even though they were no longer part of, or had never been part of, the executive chamber, according to the report.

Lacewell and Cohen were also involved in discussions about how to weaponize Boylan’s files and gathered intelligence on a former assistant named Kaitlin, whom the governor ogled by having another staffer record a phone conversation with her, the report said.

Lacewell also did not refer Charlotte Bennett’s or Lindsey Boylan’s complaints to the state Governor’s Office of Employee Relations, despite being aware of them, and Cohen participated in efforts to compile and spread opposition research about the attorney general’s investigators, the report said.

In addition, DeRosa asked Schwartz, who Cuomo had appointed as the state’s vaccine czar, to call several county executives and ask them whether they stood with the governor after several allegations were reported publicly in March. Schwartz told investigators that he recalled saying, “I’m not calling you about vaccines, I’m calling because you’ve taken a public position calling for an independent investigation by the attorney general’s office and you’re going to wait for the outcome of that investigation. Is that still your position?” The calls also became public, and Schwartz’s actions are currently the subject of a state ethics investigation, the New York Post reported.

Investigators faulted Cuomo’s cabal for putting their personal loyalty to the governor ahead of taking allegations seriously and reporting them.

“We find that all of these aspects of the executive chamber’s culture … contributed to creating an environment where the governor’s sexually harassing conduct was allowed to flourish and persist,” the report said. “Whether driven by fear or blinded by loyalty, the senior staff of the executive chamber (and the governor’s select group of outside confidantes) looked to protect the governor and found ways not to believe or credit those who stepped forward to make or support allegations against him.”

An attorney representing the governor disputed the report’s findings, saying that investigators “purposefully omit[ted] key evidence.”

Even if Cuomo resigns in the coming weeks, dislodging officials he appointed over the course of his decade-plus in office won’t be so easy.

Lt. Gov. Kathy Hochul, who would become the next governor if Cuomo were to step down, will likely install new staff in the executive chamber, but might be hesitant to clean house in an election year. Board members on the MTA serve concurrent terms with the governor and wouldn’t be eligible to be replaced until Jan. 1, 2023. Cohen’s Port Authority term won’t run out until June 30, 2024.

“If she asked them to resign, they would. That’s happened with other governors,” said Rachael Fauss, a senior research analyst at Reinvent Albany, a government accountability office. “But, who is to say she would appoint new people since she’s been a part of the administration as well.”

Cuomo’s sexual harassment scandal could hinder the MTA’s long-term recovery after the pandemic nearly obliterated its finances. The authority’s acting leaders canceled a press conference, that was billed as a major announcement, on the day James’ report was released (the subject of the announcement remains undisclosed).

Transit advocates question whether a leadership vacuum and the governor’s political crisis could sidetrack the MTA’s congestion pricing plan, which would toll most motorists driving into Manhattan’s main business district to pay for public transit improvements that the commercial real estate industry, among other sectors, says are urgently needed.

“Millions of riders depend on fast, frequent, reliable transit service,” said Danny Pearlstein, a spokesman and policy director for the transit advocacy group Riders Alliance. “Our whole recovery depends on it. Riders can’t afford to have the transit system used as a distraction or a scapegoat. Its future needs to top the agenda of anyone serving as New York’s governor.”