As Eviction Crisis Looms, Florida Hasn’t Given Out $1.3B in Rental Aid

By Chava Gourarie July 28, 2021 5:21 pm

reprints

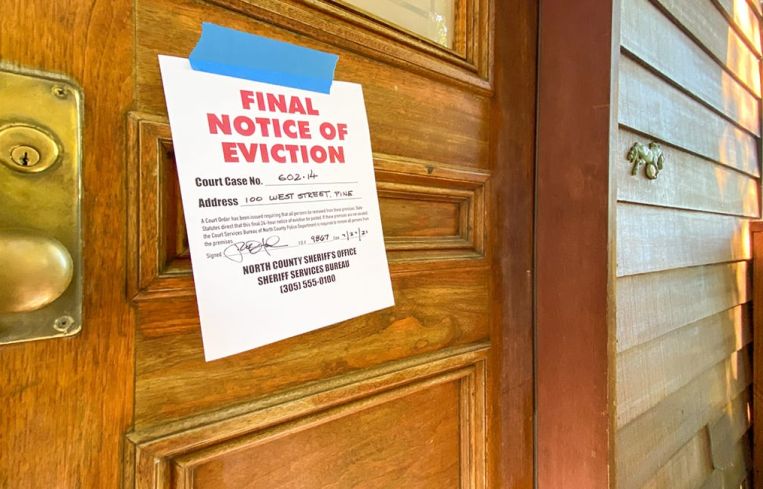

Come Monday, thousands of renters in South Florida will be at risk of eviction.

The federal eviction moratorium — first instituted in September 2020 during the height of the coronavirus pandemic — expires Saturday, ending a nearly year-long freeze on evictions.

The onslaught is expected to begin next week, despite the $46 billion that Congress has allocated to rental aid nationwide, as only 6.5 percent of that has been disbursed to those who need it.

Florida received a total of $1.4 billion in federal dollars to distribute to tenants and landlords, split between the state and local governments, but has barely doled out any of it.

The DeSantis administration has disbursed just $1.5 million in the first half of the year, out of the $871 million allocated to the state, according to the U.S. Department of Treasury. That leaves the state with another $869.5 million to spend. Local Florida governments have done a bit better, giving out $109 million of the $570 million allocated to them.

Meanwhile, the need is enormous. South Florida outpaces the rest of the nation in the percentage of renters at risk of eviction, which stands at 14.7 percent nationwide, and the amount of rent owed, according to an analysis by The New York Times.

In Miami-Dade County, 16.7 percent of renters are at risk of eviction, with an average of $4,800 in owed rent, which is much higher than the national average of $3,800, per the analysis.

Broward County has an even larger amount of per-renter debt: 16.2 percent of households are facing eviction with an average of $5,008 in debt, while 13.7 percent of Palm Beach households at risk are behind on $4,658 in rent on average.

To make matters worse, Florida rents have risen sharply over the past year as remote workers from cities like New York have fled south, and others moved in temporarily to escape pandemic restrictions. In the Miami metro area, rents have risen 15.9 percent since last July, compared with 10.3 percent nationwide, according to Apartments.com.

That translates to more pressure from landlords to raise the rent on existing tenants, or to remove non-paying tenants and replace them with renters at a higher price point.

But, despite the generous amounts of available rental aid from Congress, the rollout of those funds has been so slow that it’s unlikely to stave off the onslaught of evictions. The bureaucratic systems are complex, differ by location, and many households are ineligible, said Jason Vanslette, a partner with Kelley Kronenberg’s real estate practice in Fort Lauderdale.

In order to be eligible for the aid in Florida, tenants must make less than 80 percent of area median income, be able to demonstrate a financial hardship because of COVID-19, and show that they are at risk of homelessness, per the state’s website.

One piece of the complex puzzle is that tenants and landlords are supposed to apply for the aid together, since the tenant has to establish eligibility and the landlord has to receive the money, Vanslette said. That needs to be simplified and renters should be able to provide a self-affidavit of need because the documentation requirements are too high, he added.

Three states and Washington, D.C., have additional protections to stave off evictions beyond this Saturday, while landlords and homeowners with government-backed loans are protected through the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA) through Sept. 30.

In addition, the FHFA announced Wednesday that all multifamily tenants whose landlords have government-backed loans must be given 30 days’ notice before moving to evict. This applies even to landlords who are not in forbearance, which was not previously the case.

Chava Gourarie can be reached at cgourarie@commercialobserver.com.