The Sherbert Group’s Tara Sherbert on Tackling Historic Rehabs Amid COVID-19

By Mack Burke November 19, 2020 12:30 pm

reprints

The Sherbert Group has made a name for itself in the expensive and turbulent niche of redeveloping historic buildings.

“We call it: ‘Turning dragons into princesses,’” said Tara Sherbert, the firm’s founder.

The company stares down the challenge of a historic repositioning from its perch as an out-and-out expert in virtually every area of the field, especially in state and federal historic tax credits.

Sherbert, herself, said she’s been involved in more than 500 such projects in her career, which began in accountancy, where she worked with historic properties and affordable housing. She launched The Sherbert Group in the 1990s, and it’s been expanding ever since.

Over time, the Pennsylvania native’s company has established clout as a multi-faceted operation specializing in the realm of state and federal historic preservation tax incentives. Through a series of subsidiaries, they offer financial and construction consultancy across the country, and they invest in, develop and manage historic properties in the Southeast. (There’s also a little, light political lobbying sprinkled in.)

“Historic renovation is what really gets our attention,” Sherbert said. “If I pick up the phone, it’s about a historic rehab. We’re called weekly to look at historic renovations, or to take them over. We have a lot of history watching these [sites] go through the good, the bad and the ugly. They are one, giant unforeseen condition, and they whisper secrets to a developer throughout the process.”

The company has 20 professionals in its corporate offices in Charlotte, N.C.; an architectural division in Raleigh, N.C.; and its property management operations are housed at each of its developments, an indication of the company’s preference to always deploy a hyper-focused, hands-on approach.

On the development side, it tackles old sites — such as textile mills, manufacturing facilities or abandoned power plants — to create mixed-use, community-oriented projects.

In October, the firm nabbed $27 million to refinance the multifamily portion of its new Drayton Mills Lofts and Marketplace mixed-use development, which was built out of an old site that previously comprised two textile mills. At Drayton, the firm has hand-selected retail and office tenants to create a small community and micro-market of sorts in Spartanburg, S.C. Sherbert said they’ve helped to buoy these tenants and small businesses through COVID-19, having used the company’s capabilities to coach them through how to get and use federal stimulus funds to stay afloat.

Sherbert has also used Drayton as a template to showcase to state and federal lawmakers the benefits of safeguarding state and federal historic preservation tax incentives.

Sherbert spoke to Commercial Observer earlier this month to discuss the challenges and rewards of historic redevelopment, her firm’s history, and how it’s held up through COVID-19.

Commercial Observer: Where are you from?

Tara Sherbert: I started my career up in the Washington, D.C., area, actually, as a [certified public accountant], and I grew up into a partnership with a national CPA firm: first, through audit and tax, and then the consulting division. I structured deals nationwide for developers and investors related to historic renovations and affordable housing that utilized federal and state tax credits.

Can you take us along the path that led to starting The Sherbert Group and its collection of companies?

As a partner of that national CPA firm, I was advising on how to put these [historic tax credit] deals together financially, but I didn’t have true boots-on-the-ground experience. I decided to leave the CPA firm and start The Sherbert Group, which started as an [accountancy] and consulting firm. Some top people at my previous CPA firm followed me into forming the consulting division.

From there, I started an investment division, and we began to structure and close deals for large, national capital. We then moved on to start the development division. We wanted to take all of our specialties — CPA, consulting and investing — and use them to begin developing ourselves. We’ve been extremely successful in that division — getting deals done without change orders, on time and under budget — providing detailed analytical approaches to what we do, which came from our CPA background.

We’ve expanded our investment and lending divisions into larger and more complex transactions, and we’ve also brought an architectural division in-house. We just recently launched our own property management division, and we’re currently expanding our construction management side, which is something we’ve been growing for the last five or six years.

Tell us about the breadth of your historic tax credits consulting practice.

Through our consulting division, we consult nationwide. We’re very technically sound, and we follow federal, state and local taxes very closely. We’re often very involved politically in getting the tax credit passed.

When the Federal Historic Tax Credit was pulled out of the code with the most recent tax reform, we had [U.S.] Sen. Tim Scott and [U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development] Secretary Ben Carson out to Drayton Mills, and gave them a tour and pleaded our case as to why the historic tax credit should stay in the code. They were on board with it.

When Scott went up in front of the [Senate] Finance Committee, he mentioned his trip to Drayton Mills; that evening, it went back into code. It took a lot of work not just from our firm, but from coalitions and senators, and speaking constantly about how these deals have such a positive impact. There’s been a lot of support from Republicans and Democrats. We try to bring federal and state representatives out regularly to see the properties and see how important they are.

I will never forget: We were having lunch the day the federal historic credit was pulled out, and we immediately went into how we change it. We just looked at each other, and said, “No, we’re going to fight.” We drove to Charleston, S.C. We were exhausted and we met with Scott that night, a Friday. We spent the time with him, letting him get his mind around it. People think change is made by these large-scale lobbyists, but in reality, change is made by a lot of hard work and grit.

How has your firm been able to manage through COVID, given the uniqueness of what you do?

As a firm, we are very conservative in our approaches; we’re very detailed and analytical. When something like COVID comes to pass, we can get through that because we’re very strong financially, and because we have been very cautious and detailed in our approach over the last 26 years of being in business. We get so involved with our businesses on so many different levels. We’re able to reach in from all angles to prop up businesses in any manner they might need.

So, as the economy ebbs and flows, we’re able to focus on businesses that may do better one year versus another. If interest rates are high, our lending and investing divisions would be exhibiting a different level of activity than our development divisions. We don’t have a desire or goal to be a super large company. We are very hands-on with everything we do, and that enables us to react quickly with an all-hands-on-deck approach.

But a lot of the last seven to eight months, I’d call treading water, trying to figure out where the river would take us.

During the first two months of COVID, it was all a blur, but we really didn’t skip a beat and haven’t taken a day off since it started. The first three months [were] a pure and utter fight. We had thought we’d be out of it in 30 days. We were reshuffling how to manage staff out of the office, working what we thought would be a 30- to 50-day pause. When that didn’t happen, we started looking at our assets.

Has it impacted the way you outfit your projects?

We’re spending a lot more time on pre-development. We’ve moved a lot of commercial office space we had under pre-development to residential. For any of our food and beverage under pre-development, we’ve looked at how we can redesign those to be post-COVID accommodating. I think that will prove to be very beneficial.

We hope to be under construction with three [projects] the next three months, and we’re finishing up [pre-development] now. [On our existing projects,] like Drayton [Mills], we spent a lot of time working with marketplace partners and a lot of time on food and beverage; looking at leases; and expanding outdoor spaces; and looking at safe, outdoor community events.

How have your other projects fared?

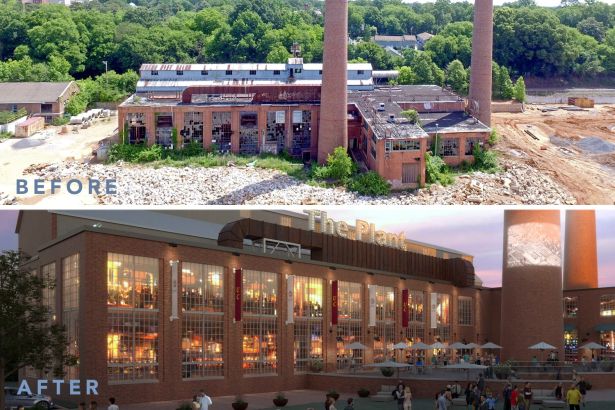

We have the [Rock Hill] Power Plant building in Rock Hill, [S.C.] It’s a historic power plant, with a massive demolition plant. We had that asset ready for construction, and it was supposed to have a food hall at the bottom, with two anchor restaurants, commercial space up the rest of the project, and a handful of apartment units at the top. We had to “CTRL+ALT+DELETE” that plan.

We had to meet every bit of the historic standard, which tends to be expensive. We had to think about how we make this work with food and beverage, which financing is shut down on, at the moment, while effectively redesigning enough units in that building to make it work with the commercial space. We had 36 different floor plans for the apartment units going in, including townhomes, trying to utilize every square foot. The design is remarkable.

We spent six months designing some really chic units, and we redesigned it around a significant outdoor event lawn — we spent a lot of time on that community feature. We added large, outdoor patios for the restaurants, which align with the inside, having areas where people can come in and pick up their food while staying distanced. There’s a significant amount of food and beverage written into the building, which lenders will not touch, so we’re having to do all of that pure equity. I hope to be under demolition on the Power Plant in the next 45 days.

Right next to the Power Plant, we have 144 new, Class A apartments that we’ll have under construction in the next 60 to 90 days — we’re finishing permit plans for that. It’ll have a parking deck, along with retail.

And then, we do have three other mill sites that are really in the pre-development stage right now. We’re waiting to see how the next couple weeks shake out. They’re great assets, great mills, all in the Carolinas. Through our investment divisions, we have several assets up and down the East Coast that are under construction and should finish in 2021.

What would you say is the most challenging aspect of a historic redevelopment?

Well, one division we don’t have in-house — and that should be changing soon — is general contracting. Finding one, and [subcontractors], who can detail everything into a square footage analysis is very difficult. You’d think [these historic rehabs] are just construction. But we color code everything within our drawings, whether it’s the scope of asbestos-based paint that exists [at the property], or the exact amount of flooring we have to replace, or beams that are rotted and need to come out.

It’s challenging to get [one] to put the work upfront into their bids, and I have no tolerance for swag bids. [Once it’s understood what specific work needs to be done,] only then can we look at it and detail it into price per square footage. It allows the sub to work effectively through the rehab, because they’re finding a lot of secrets [about the property] in that pre-development bid phase. But it also gets all the parties on board and greatly reduces the amount of change order requests that a sub would provide, which we would tend to not accept in most cases.

We’ve watched developers go for the lowest bidder, and then deal with the consequences with that during construction. That can be disastrous in a historic renovation.

While you benefit from a deep track record, how difficult is it to get lenders on board with these projects, especially now?

It’s a lot less challenging now than when we first started this. Like [the Rock Hill] Power Plant, we’ll underwrite it upfront to go in at 40 percent loan-to-cost, so we don’t spend much time begging for debt. As a company, we love low leverage. We want to put capital in and not take fees out up front, and enjoy strong cash flow based on performance, which is how it should happen.

We’ve learned to underwrite low debt into these deals, even on a refinance like Drayton Mills. When we refinanced it, we could’ve taken more debt, but we didn’t. We just refinanced the rate.