Inside the Development Battle That’s Dividing Flushing

By Rebecca Baird-Remba November 30, 2020 6:12 pm

reprints

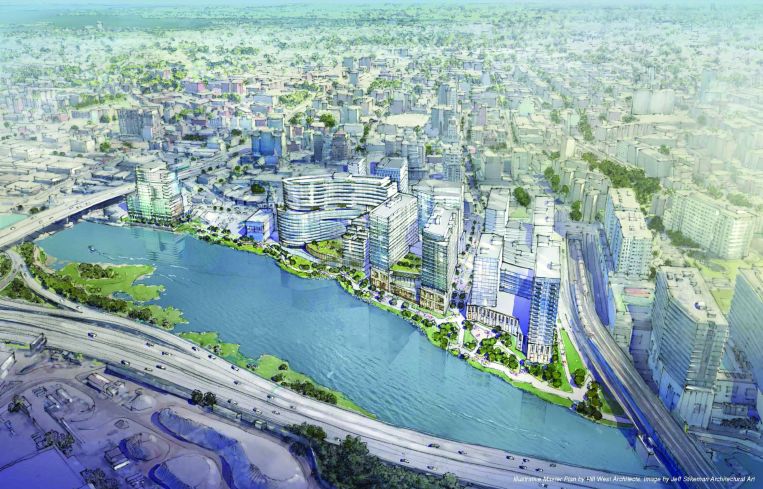

A community battle is brewing in Flushing over a controversial plan to build 13 towers with 1,700 apartments, hotels, retail and office along an industrial stretch of waterfront in eastern Queens. The City Council is expected to vote on the plan in the next month and a half, but the project is buffeted by pushback from unions, local activists and politicians who want more affordable housing and union labor in the sprawling development.

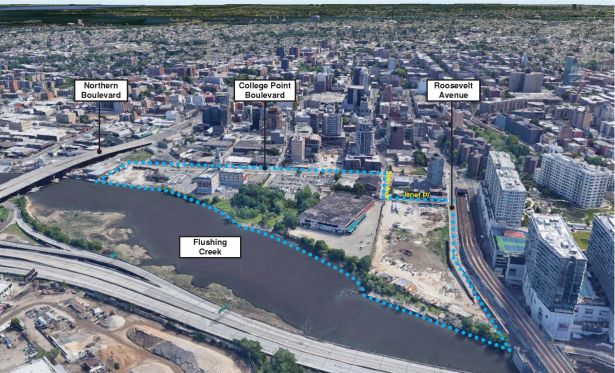

Three Flushing-based developers—F&T Group, Young Nian Group and United Construction & Development Group—are working together on the megaproject, which stretches across 29 acres of waterfront along the heavily polluted Flushing Creek. The group’s proposal, dubbed the Special Flushing Waterfront District, calls for 1,725 apartments, 879 hotel rooms, 400,000 square feet of community facility and office space, 286,930 square feet of retail and 1,735 parking spaces.

However, only 70 to 90 of those apartments will be income-restricted because the developers are rezoning just 10 percent of the project area. The city’s Mandatory Inclusionary Housing program requires developers to set aside up to 30 percent of their units as affordable housing, but it can only be applied when a property’s zoning is changed.

John Liang, president of Young Nian, said that the Department of City Planning approached him and the other two firms—which own contiguous waterfront properties—a few years ago about going through the uniform land use review process (ULURP) to create a special waterfront district, which would allow city planners to oversee the development and cleanup of the Flushing waterfront. He said that the three development firms were willing to work together in order to create roads and a public waterfront that would benefit both their projects and the neighborhood.

Liang pointed out that the builders could have gone their separate ways and built a total of 1,400 apartments without changing any zoning or getting a special permit. But they wanted to avoid building more megaprojects in the style of Skyview Parc—a massive three-tower condo project and mall in Flushing—with hefty parking requirements and little coordination on important amenities like waterfront access and roads, he said.

“We bought the land around this time three years ago,” Liang said. “At that point we purchased a full set of plans that had already gone through the Buildings Department because the zoning never changed. We’re not gaining one single square foot of density with this ULURP. My southerly neighbor even got their plans approved and was shovel ready. Then City Planning spearheaded this whole waterfront district effort.”

As the project reaches the end of the year-long review, local politicians and Queens activists have been turning up the political heat, holding public rallies and publishing op-eds on why the development should not be approved. The opponents, which include community groups like Minkwon Center, Chhaya CDC and the Greater Flushing Chamber of Commerce, argue that the development should provide significantly more affordable housing and a school if the developers are going to build more than 1,700 apartments.

The developers argue that they didn’t need to go through the public land use process at all. Much of the development’s 3 million square feet could indeed be built under the existing zoning, with the exception of one site that is currently zoned for heavy commercial uses. If the developers win approval for the zoning change, that property will be developed into a 300-unit building, of which 25 to 30 percent will be affordable housing. Perhaps the largest benefit of the land use change will be a reduction in parking requirements, from roughly 3,200 parking spots under the current zoning to 1,500 spots under the special district rules.

The developers, operating as a consortium known as FWRA LLC, also plan to build 124,000 square feet of publicly accessible streets and sidewalks, a 400-foot-long stretch of public waterfront, and sewer and bulkhead upgrades for the waterfront along Flushing Creek.

Given their ability to build most of the project without a zoning change, the developers could walk away from the ULURP process now if they can’t reach a deal with the City Council. But they have already spent millions on land use lawyers and engineers, so they hope to see the project through to the end of public approvals.

John Choe, executive director of the Greater Flushing Chamber of Commerce, said he feels that the developers did not approach the land use process correctly and did not consult with the community enough before entering ULURP last year. His organization, along with MinKwon and Chhaya, filed a lawsuit against the Department of City Planning last June, charging that the city did not conduct the project’s environmental review process properly because it did not require the developers to create an environmental impact statement (EIS).

“Here we are, an Asian immigrant community being deprived of a basic part of the land use process,” said Choe. “That’s a serious defect in the process and in the actual project itself.”

The developers did hire Langan Engineering to create a 722-page environmental assessment statement, which they say addresses many of the same issues—such as residential displacement and traffic congestion—that an EIS would examine.

Choe, however, remains unconvinced.

“It doesn’t follow the same rigorous standards that an EIS would require,” he said. “We don’t know the social and economic impacts on the surrounding neighborhoods. We don’t know how it will affect schools, displacement effects on small businesses in the community. City Council members asked those questions [at a council hearing last week] and the developers didn’t have those answers, because they didn’t go through the EIS process.”

He also suggested that the developers’ campaign contributions to the local councilman, Peter Koo, had compromised the land use process, and pointed to a local community board member’s consultant work with the development team as further evidence. Choe, who voted on the Flushing project as a member of Queens Community Board 7, is one of several candidates running to replace Koo on the City Council after he leaves office next year.

“Is this person who represents us in the council someone who can view this project as a neutral observer or is he like the community board members who are being paid by the developers?” asked Choe.

After last week’s multi-hour council hearing on the project, Queens Councilman Francisco Moya, who chairs the council’s zoning subcommittee, released a joint statement signed by 10 other councilmembers who opposed the project in its current form. They claim the proposal “ignores the real, urgent needs of the Flushing community. We believe it would be irresponsible to approve the application without deep community benefits like real affordable housing and commitments to provide good jobs for local community members…. Approving this rezoning as it currently stands would be a grave mistake.”

On the other hand, City Councilman Peter Koo, who represents Flushing, supports the project and has been trying to persuade his fellow councilmembers to do so as well. The development must get approval from the zoning subcommittee as well as the full council in order for the zoning changes to be made official. Four years ago, Koo shot down a city-led rezoning that included part of the Special Flushing Waterfront District, pointing to concerns about the neighborhood’s infrastructure and parking needs.

Mitch Korbey, a real estate attorney and chair of the land use group at Herrick Feinstein, noted that the council typically approves rezonings as long as the local council member supports them. He compared the Flushing plan to the proposed rezoning of Industry City in Sunset Park, Brooklyn, where the owners recently withdrew their application in the face of growing opposition from a long list of local politicians, including Brooklyn’s congressional delegation, several state senators and the neighborhood’s councilmember, Carlos Menchaca.

“You have members outside the district not supporting this and not deferring to the member who does support it,” said Korbey. “It’s akin to Industry City, and now Industry City will move forward with a litany of private projects that don’t have any community inputs.”

Council approval for the Flushing development, however, hinges on negotiations with two major labor unions—service workers union 32BJ SEIU and the Hotel Trades Council—which wield a significant amount of political influence in the five boroughs. Southeast Queens Councilman Donovan Richards, who was just elected Queens borough president and sits on the zoning subcommittee, recently told The City that he planned to vote down the project if a labor agreement was not reached.

The developers, who plan on running their construction sites with both union and non-union labor, contend that union hotel wages would make it difficult for a hotel in Flushing to earn a profit.

“The hotel trade union historically has not been successful in coming to Flushing,” said Liang. “The new immigrants want to work in their own community, and they didn’t want to join the union. In order to move this project forward we are in close discussion with the unions in order to give them a foot in the door.

“You have to keep in mind,” he added, “that based on our own research, the average [hotel] room rate is 77 percent lower than Manhattan, so we’re very cost conscious about running our hotels in the future. Occupancy is well below 30 percent. They’re not covering their costs, and, when you’re talking about union labor, that adds a very significant layer of cost. We truly hope that we will reach an agreement so that the union will support us.”