Pay Gap Widens in CRE, Even as Diversity Initiatives Take Hold: Report

By Chava Gourarie October 27, 2020 2:03 pm

reprints

The proportion of women in commercial real estate’s professional ranks has remained flat for 15 years, but a younger generation with higher ambitions may turn the tide, according to the latest diversity report from CREW Network, a 31-year-old association for women in the field.

The benchmark report on gender and diversity in commercial real estate, published every five years since 2005, tracks a variety of diversity metrics that include compensation, job satisfaction and upward mobility. Capital One Financial Corp., the International Council of Shopping Centers, the National Multifamily Housing Council, and the Society of Industrial and Office Realtors funded the report, which is based on the responses of 2,930 commercial real estate professionals who participated in the study.

The primary statistic — the number of women in the commercial real estate industry — has hovered between 35 percent to 37 percent since 2005, coming in at 36.7 percent in the latest data gathered between Jan. 2 and March 31. When broken down by position, the numbers show more variability. Women made up nine percent of the C-suite in 2020, a five percent increase from 2015, but that was matched by losses on the senior vice president and partner level, where women dropped from 27 to 22 percent, an 18.5 percent decline.

“I’m not discouraged, but I am disappointed,” Wendy Mann, CEO of CREW Network, said. “Companies have made more of a concerted effort to actually recruit and promote women, so the results this time were very disappointing.”

Even more concerning to CREW were the results regarding compensation.

With all earnings factored in, including commissions and bonuses, across all positions, the compensation gap came in at 33 percent, nearly 11 percent higher than in 2015.

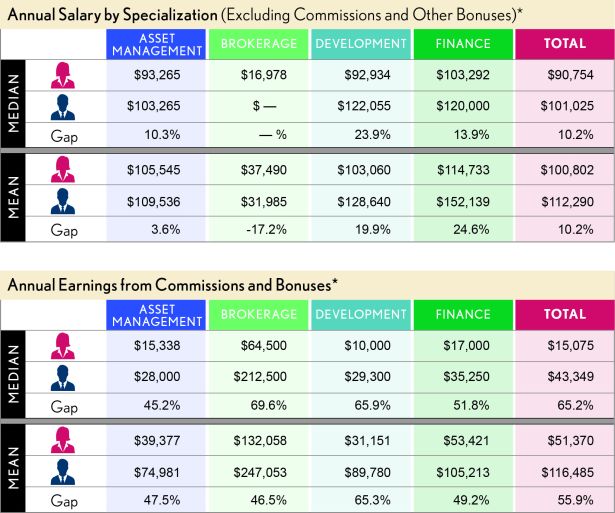

The gap begins with the base salary, with men reporting an average $112,290 base salary and women $100,802, a 10 percent discrepancy. That gap is wider for women of color, where it ranges from 80 cents (for every dollar that men earn) for Latina women, 85 cents for Black women and 86 cents for Asian women.

Once commissions and bonuses are factored in, the gap widens further, especially at the highest rungs of the ladder. On average, women make almost 56 percent less than men from bonuses and commissions across finance, asset management, brokerage and finance roles, and that gap expands to 71 percent for Black women.

“That alone just makes me really question what’s happening out there,” Mann said. “If a Black woman or Hispanic woman is making 74 percent less doing the same job, we have to ask ourselves, what’s going on there?”

When it comes to bonuses and commissions, one factor could be that women are at a disadvantage in an industry heavily reliant on relationships. “I question whether women are getting access to the same opportunities,” Mann said.

The biggest retreat, however, came at the entry level. In 2015, entry-level compensation was roughly equivalent for men and women, with a two percent gap. In 2020, the gap had widened to nine percent, with women reporting an average starting salary of $62,828, and men $70,294.

“Once you come in behind, it’s very hard to make up,” Mann said. “How will they ever close that gap?”

While compensation numbers are in the red, the metrics around career trajectory are more promising. The number of women who say they aspire to the C-suite increased from 28 percent in 2015 to 32 percent in 2020, though that’s still behind the 43 percent of men who aspire to the highest executive echelons.

What’s encouraging, Mann said, is that younger women are more likely to aspire higher, with 36 percent of women under [the age of] 40 aiming for the C-suite, compared with 26 percent of women over 50. Mann said that could indicate a cultural shift, where younger women have a wider sense of possibility and a mindset of “Why wouldn’t I go for the C-suite? I can do it.”

There are now plenty of examples of successful women in real estate. “Perhaps, that’s an influence as well. Young women see role models now, that two or three generations [ago], they wouldn’t have had that,” said Mann.

But, while ambition could indicate that younger women don’t face the same barriers as before, it could also mean they haven’t faced them so far. “They don’t see the limitations yet,” Mann said.

Career satisfaction among women has dropped since 2015, after an uptick, while men’s career satisfaction has increased. And that could be because women have higher expectations and feel like there should have been more progress.

“Women are receiving lower pay, lower mobility, less access to leadership roles,” Mann said. “Maybe women are getting frustrated. The lack of progress could be taking its toll.”

It could also be adding to a longer term, larger problem. Peyton Johnson, a Savills broker in her 20s, said the dearth of women in the C-suite is true across many industries and is somewhat built into the way business gets done.

“A lot of it is the social capital that you accrue by having things in common with the people who are already at the top,” she said, during a Commercial Observer panel that addressed the issue.

Another factor, Johnson said, is the way that parenting and caretaking are viewed differently between genders.

“One of the most daunting things is the roles at home being uneven, which I think pervade society as a whole,” she said. “I remember being a broker in D.C. and calling to set up tours, around 4:00 or 5:00 [p.m.], and a lot of the male brokers would say, ‘I can’t do that; I’m on Daddy duty.’ But I never heard female brokers say that, because there’s still something of a liability to what motherhood might mean.”

When it comes to ethnic and racial diversity, even if companies keep track, few make the data public, so it’s harder to get an accurate picture of how many people of color work in commercial real estate. It’s, nevertheless, obvious that there’s work to do, Mann said.

One thing that needs to change is intentionally recruiting from outside of a company’s circle of known contacts. “We need to be more intentional about how we’re bringing people into the industry,” Mann said.

In one company, a recruiter realized that all of their intern positions went to the children of employees, so they implemented a policy where only five of those slots were open to employees’ children in order to leave space open for outsiders.

While the numbers might not reflect it yet, it’s clear that a cultural shift is taking place. Both external and internal factors, such as human resources mandates, employee demands and top-down shifts, are forcing companies to evaluate their performance when it comes to diversity, inclusion and equality, and to make improvements, per the report.

“Anyone 30 and under is saying, ‘I don’t need this,’” Mann said. “It will hurt companies in the long run. You can hire all the women you want; they’re not going to stay if the environment is not inclusive.”