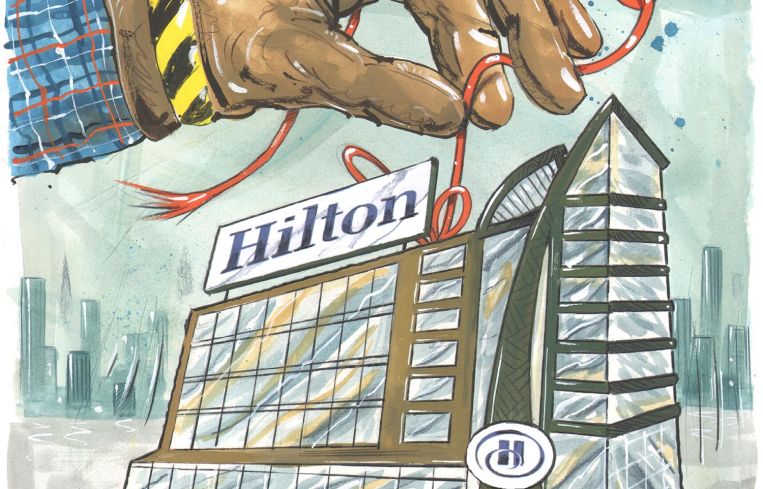

Hotel Owners and Their Unionized Workers Fight Over NYC’s Declining Hotel Revenues

By Rebecca Baird-Remba October 27, 2020 2:08 pm

reprints

The New York hotel industry and its union are locked in a financial cold war triggered by the coronavirus pandemic.

Many of the city’s largest hotels have been forced to close as New York City tourism numbers reach their lowest level in decades. Now, some of these hotels can’t afford to reopen with a handful of guests and still pay their unionized employees’ wages and benefits, which typically total more than $50 an hour.

And every day it seems the list of hotel closures grows longer. In March, the city’s biggest hotel — the New York Hilton Midtown at Avenue of the Americas and West 53rd Street — closed its 1,878 rooms indefinitely. The 478-room Hilton Times Square also shuttered on Oct. 1. And the 1,105-room Roosevelt Hotel announced last week that it would shut its doors for good after a century in business near Grand Central Terminal in Midtown.

Fifty-eight percent of Manhattan’s hotel rooms were still closed as of September, according to a quarterly report from PricewaterhouseCoopers. More than 61,000 of the city’s 129,000 rooms had not reopened by early September, and 2,700 of those are expected to remain closed permanently.

Several hotels that closed in March have reopened in the past two months, including the Baccarat Hotel in Midtown, the Equinox Hotel in Hudson Yards, The Beekman Hotel in the Financial District, the Dream Hotel Downtown in Chelsea, the Andaz 5th Avenue by Bryant Park, the InterContinental New York Barclay in Midtown East, and the InterContinental Times Square.

Some hotels have been able to reopen — or avoid closing long-term — by laying off the majority of their employees for the foreseeable future. The 800-room Westin Grand Central laid off 388 employees in March and has not brought them back, according to state WARN Act notices. After laying off 207 employees in March, the Warwick Hotel in Midtown West brought back a skeleton crew of 20 workers to reopen the hotel’s 426 rooms last month; the other 187 employees remain in employment limbo.

Statewide, New York has lost 43,000 hotel jobs since COVID-19 first struck in March, according to the American Hotel and Lodging Association. There were 113,000 hotel jobs in the state before the pandemic.

Meanwhile, the powerful New York Hotel and Motel Trades Council has pushed for protections and special severance packages for its 39,000 members employed at hotels. The union lobbied the City Council to pass a measure in September requiring any hotel that changes hands or enters court-ordered receivership to retain employees for at least 90 days at the same or higher wage.

And, due to an arbitration decision issued the same month, hotel owners and operators who decide to remain closed indefinitely must pay their laid-off workers the severance money that they would have received if the hotel had permanently closed. Alternatively, workers can opt to receive weekly bridge payments that cover the difference between state and federal unemployment benefits and workers’ full-time compensation. The law will help 28,000 union hotel workers who have been laid off since March.

Only 9,000 unionized hospitality workers have been able to go back to work in the city, constituting less than a quarter of the hotel union’s membership. As costs mount, the hotel industry argues that more unionized hotels will shutter for good, keeping employees out of work for months, if not years.

Pay for the average union hotel employees starts at $34 per hour, plus an extra $20 per hour to cover benefits like health insurance and pension payments. So, the average union hotel worker in New York City costs about $100,000 a year to employ, according to industry trade groups. Many hotel owners and hospitality experts argue that hotels have no incentive to reopen if they can only rent 10 or 15 percent of their rooms, which would generate enough to cover employees’ salaries and not much else. A 1,000-room hotel typically has about 150 employees.

“The city as a whole used to average $29 million a night in hotel revenue,” said one hotel industry source who asked to remain anonymous. “A single [large] hotel was going to be making $1.5 million. And, if you have 10 employees, that’s $1 million. How do you pay for other things? So, that’s the quandary we face. If you’re a worker, you’re not going to take a 15 or 20 percent pay cut.”

It doesn’t help that developers kept building hotels in New York City, even as demand began to soften and the market for rooms became somewhat saturated last year. The Big Apple saw 67 million tourists last year, according to NYC & Company, the city’s tourism arm, and it added 3,900 new hotel rooms in 2019.

Foot traffic in major tourist destinations like Times Square has rebounded to some extent, but still remains down about 70 percent from last year. “The Crossroads of the World” usually attracts between 350,000 and 450,000 people daily. Most days this fall, however, Times Square averaged more than 100,000 visitors, with one day in October bringing in 146,000 people.

Occupancy rates have recovered somewhat since the height of the pandemic, when less than a third of the city’s hotel rooms were occupied. For the week ending Oct. 17, 40 percent of the city’s hotel rooms were rented, according to hotel data firm STR. But that number may be deceiving, because the city has converted a number of hotels into homeless shelters or isolation hotels for New Yorkers infected with COVID-19.

“The homeless are propping up the hotel industry,” said one broker in the hospitality industry. “It’s like 30 or 40 percent of the rooms.”

The hotel trades union blames declining tourism numbers for hotels’ struggle.

“The contract did not prevent any NYC hotel pre-pandemic from operating and quite profitably,” said a spokesman for HTC. “And, as evidenced by the many union hotels that have reopened recently, the issue driving reopenings is about demand, not the terms of the union contract. The pandemic has driven down demand and occupancy in every major market in the country.”

Owners who keep their hotels closed are now required to pay out severance costs or the aforementioned bridge payments. That puts hotel owners who may already be defaulting on their mortgages in a bind.

“There is no money to pay severance,” said the broker. “The operator is on the hook for the severance costs. When times are good, the owner can reimburse them for these unfunded pension costs. But, now, the union is looking to the operators, who are the only people with a balance sheet. In some of these situations, the borrower is trying to give the keys back to the lender, too, and the lender doesn’t want to take title to the asset.”

Hotel owners can only exit the union contract by declaring bankruptcy. And, even under those circumstances, they must meet with the union and a mediator and attempt to work out a deal.

“My view is it’s going to force a lot of people into bankruptcy,” said the broker. “The union has leverage to continue to force people to pony up money, until the owner says, ‘I have to go into bankruptcy.’”