SL Green Opens One Vanderbilt as COVID-19 Keeps Offices Empty

It might be a very long time before Midtown gets another ground-up piece of new construction that will change the skyline. But for now the area can bask in the glow of One Vanderbilt.

By Nicholas Rizzi September 14, 2020 11:10 am

reprints

SL Green Realty Corp. is set to finally cut the ribbon on its massive $3 billion, 77-story One Vanderbilt tower in Midtown East this afternoon. The opening capped a nearly 20-year journey for SL Green to bring some much needed new development to the neighborhood’s aging office stock.

To get the project off the ground, SL Green needed to acquire five adjacent buildings on Madison Avenue, push through a lengthy rezoning process for the area that nearly fell apart, and fight a $1.1 billion lawsuit. And it’s opening during what could be the project’s biggest challenge yet: An unprecedented global pandemic that paused construction, brought Manhattan leasing activity to a grinding halt, and left some pontificating about the death of the office as we know it.

Despite all of that, SL Green President Andrew Mathias is still confident in the project. In an interview before One Vanderbilt’s grand opening, Mathias said all the things that made One Vanderbilt attractive to tenants before — a new building with wide-open floor plates close to Grand Central — are even more important today as workspaces designed to minimize the spread of disease are at the forefront for most companies looking for new offices.

“A lot of things people are looking for today [ventilation systems, touch-less entry] are built into the base package of the building,” Mathias said. “That’s driving a lot of tenants to look for new construction. They can space out more efficiently as well in One Vanderbilt because our floors are column-free.

“New construction still draws a lot of interest and still has some pricing power,” he added.

And Mathias’ confidence is not without merit. One Vanderbilt is currently about 70 percent leased, with the remaining space mainly on the upper levels of the tower. Tenants so far include TD Bank, the Carlyle Group and Greenberg Traurig. In April, soon after the lockdown started in New York, SL Green announced it had signed deals with InTandem Capital Partners and Sagewind Capital too for a combined 10,165 square feet in the building, while Oak Hill Advisors took another 23,848 square feet. Tenants like these are expected to start moving into One Vanderbilt in November.

Things have looked far less rosy for the rest of Manhattan. New leasing plunged recently to record lows, with just 3.3 million square feet of space taken in the second quarter, a 57.8 percent drop from an already dismal first quarter, according to Savills.

Last month, a report from Colliers International found that offices for sublet make up 23 percent of all available space in Manhattan, the highest amount since 2010, while absorption was a negative 3.84 million square feet.

Mathias, however, said activity has still been relatively strong at One Vanderbilt during the pandemic with the developer in talks with several tenants to finalize deals.

“We do have decent tenant activity now, even with the current status of New York,” he said. “We are trading proposals actively with several tenants, both in the lower and high-rise portions of the building.”

Even if opening an office tower during a global pandemic that forced most workers into their home might be a grim prospect for some, others see it as a positive sign for the future of New York City.

“It really tells the story of New York and New Yorkers: We don’t give up,” said Alfred Cerullo, president and CEO of local business improvement district the Grand Central Partnership. “The opening couldn’t be at a better time when we need to look to the future and think about a better tomorrow.”

The history of One Vanderbilt started in 2001, when SL Green picked up the 22-story 317 Madison Avenue for $105.6 million with plans to simply renovate the property.

“At that point, we really didn’t view it as a development site at all because there were four other buildings on the block,” Mathias said. “We went about redevelopment. We actually signed a 20-year lease with what was then Commerce Bank, which turned into TD Bank, around 2004.”

That plan changed in 2008, when the rest of the buildings on the block started coming up for sale and SL Green started picking them up, acquiring the final site in 2011. Then SL Green switched gears to demolish the existing buildings and develop a new office tower in its wake.

The idea was welcome news to some in the neighborhood as Midtown East’s aging office stock didn’t fit the needs of modern companies, pushing tenants to new projects around Manhattan such as Hudson Yards and the redevelopment of the World Trade Center site, Cerullo said.

“More than half of [Midtown East’s] building stock back in the early 2000s was 75 years old or older,” Cerullo said. “The floorplates of them were based on a business model that was not the business model of today and not the business model of the future.”

SL Green though faced a giant hurdle to building a super-tall office tower in Midtown East: the neighborhood’s zoning. Midtown East’s previous zoning laws dated from the 1960s and limited the height of new buildings while hampering the owners of existing tall towers grandfathered in.

“You had the old building stock, but an owner couldn’t even build what they had because the underlying zoning was lower than their building,” Cerullo said. “Who’s going to empty their building out and then take a building down only to build it smaller?”

A lifeline came from then-Mayor Michael Bloomberg, whose administration pushed through rezonings in more than 120 neighborhoods.

In 2012, Bloomberg pitched a plan to rezone a 73-block area around Grand Central Terminal that would allow buildings taller than the Chrysler Building to rise in Midtown East, the New York Times reported. The rezoning plan died in 2013, when the City Council voted it down as Mayor Bill de Blasio was set to take office, according to the Times.

“Those were some pretty dark, dark days,” Mathias said. “We needed that rezoning for the building to become financially viable. We had worked very hard to come up with a plan that we thought was going to pass, and the speaker brought it for a vote. Then things changed overnight.”

All was not lost. In 2014, de Blasio publicly stated his intention to move forward with a rezoning plan for Midtown East, this time with a larger focus on getting public benefits from developers. He split it into two phases, the first one tackling Vanderbilt Avenue between 42nd and 47th streets and a large second one targeting the rest of the neighborhood.

The Vanderbilt Corridor rezoning passed in 2015, and allowed developers to build higher along Madison and Vanderbilt avenues than existing zoning allowed and apply for permits to purchase air rights from nearby buildings. For One Vanderbilt to get approvals to rise to 1,401 feet — the second-highest office building height in the five boroughs, behind only 1 World Trade Center — SL Green transferred the air rights from the Bowery Banks Savings Building and agreed to pay for $220 million of transit and public space improvements in the area.

“It was sort of one of the first public-private partnerships that have been done in that fashion,” Mathias said.

In 2017, the City Council unanimously approved the rezoning for the rest of Midtown East, allowing other new high-rise towers to crop up more easily in the neighborhood.

“While in 2013 we may have felt somewhat defeated after all the advocacy, hard work and investment made in the process, what we have now for this community and the world’s central business district is a much more superior toolbox of opportunity for new development,” Cerullo said. “One Vanderbilt is a prime example.”

With its zoning in hand, it seemed it was all systems go for One Vanderbilt until the owner of Grand Central Terminal, Midtown TDR Ventures, filed a $1.1 billion lawsuit in 2015 against SL Green and the de Blasio administration. The lawsuit argued that the city violated its property rights when it approved One Vanderbilt without needing to buy air rights from Grand Central. The suit was eventually settled in 2016, and One Vanderbilt finally broke ground that year. In 2017, SL Green sold a 29 percent stake in the project to the National Pension Service of Korea (NPS) and Hines.

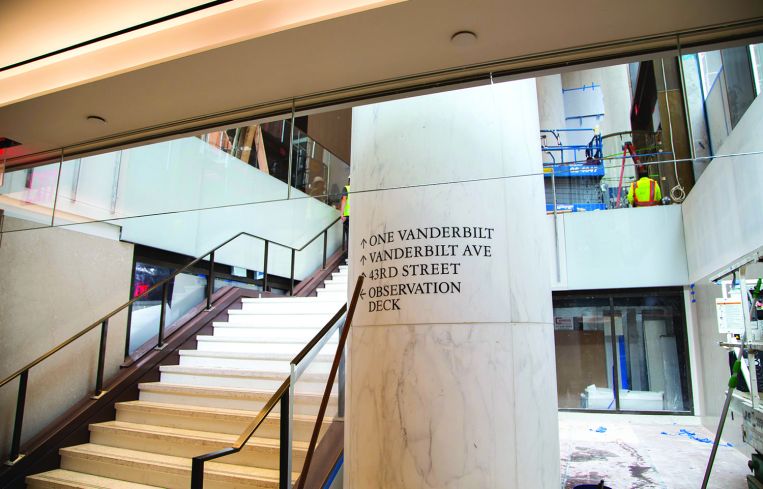

One Vanderbilt topped out in 2019, and was originally slated to open on Aug. 4, with the observation deck set to open in 2021. The pandemic forced SL Green to shut down construction for nearly two weeks.

“We’ve implemented a bunch of measures [at the site], temperature checks at the front gate, social distancing monitoring on each floor,” Mathias said. “Fortunately, we haven’t had any cases at the site.”

And, while Mathias is confident the pandemic hasn’t derailed One Vanderbilt much, the company has faced some troubles elsewhere.

Its stock price (before One Vanderbilt opened) was down by about 39 percent since the start of the year. Early in the pandemic, SL Green’s $815 million sale of the Daily News Building to Jacob Chetrit fell apart.

It has also in recent months started to list buildings around the city for sale to help buy back stocks and provide it with funds to survive an economic downturn. In May, SL Green unloaded its retail condominium at 609 Fifth Avenue for $168 million at a time when the pandemic has battered retail.

Still, the city’s largest commercial landlord remains bullish on New York’s future. SL Green is currently redeveloping One Madison Avenue — building a glass tower on top of the existing office building — and in May sold a 49.5 percent stake in that to NPS and Hines.

“It’s gotten a lot of great early tenant interest,” Mathias said. “We’re confident that’s going to be a big success.”