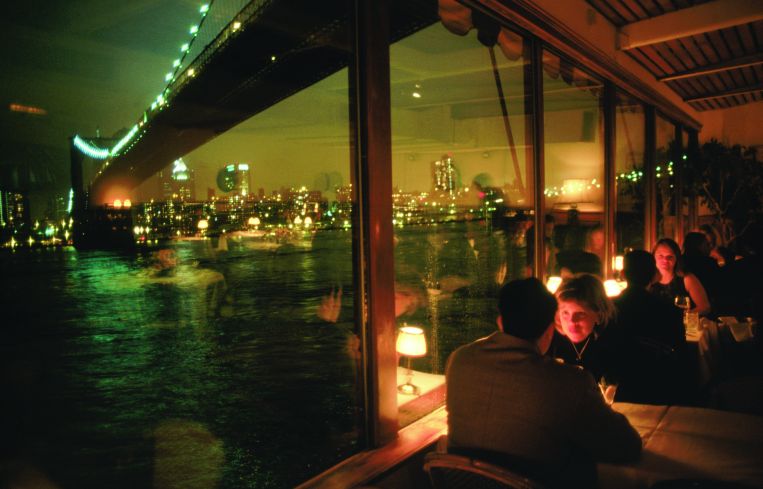

Let the River (Café) Run!

The River Café has seen its share of troubles. COVID-19 is by far the worst.

By Steve Cuozzo June 8, 2020 2:05 pm

reprints

It took Buzzy O’Keeffe twelve years to launch his fabled River Café on the Brooklyn waterfront in 1977. Since then, the restaurant — a potent incubator of modern-American cuisine and a favorite of locals and tourists alike — has survived a biblical-scale cavalcade of catastrophes.

The city’s crime and decay through the 1980s deterred spending. A nor’easter in December 1992 swamped the place with East River seawater — “the highest tide ever seen at the time,” O’Keeffe said. The 9/11 terrorist attack devastated business when River Café’s postcard view of Lower Manhattan from the foot of the Brooklyn Bridge gave way to a hollowed-out skyline and toxic smoke plumes.

In 2008, a man-made waterfall next door, part of a city art installation, almost destroyed the linden and birch trees that O’Keeefe planted in the 1970s. The Great Recession wiped out expense account spending. Superstorm Sandy’s sea surge in 2013 nearly sunk the River Café and closed it for a year of rebuilding.

Most recently, O’Keeffe’s company settled for an undisclosed sum a lawsuit over alleged tips-stealing — a now-common legal ambush that owners regard as a shakedown, which also cost Jean-Georges Vongerichten, Lidia and Joe Bastianich and Thomas Keller a bundle.

Now comes the pandemic, worse than all of the previous travails combined.

“I wouldn’t put it as a curse,” O’Keeffe said of the disasters. “It happened to everyone.” But maybe not as cruelly as to River Café. Its plight has gone overlooked in media coverage focused on Manhattan landmarks such as Le Bernardin and Union Square Café and on some shuttered “iconic” bars.

But River Café has been one of the city’s premier celebration venues and an essential institution since the day it opened in 1977, when “Dumbo” meant only a flying elephant. It spawned the careers of influential chefs Larry Forgione, Charlie Palmer and David Burke. It draws boldface clientele including Spike Lee, Sarah Jessica Parker, Jimmy Kimmel, Emily Ratajowski, Adam Driver, Tyra Banks, Daniel Craig and Rachel Weisz.

Bucking anti-formal trends, it keeps the faith with white tablecloths and polished service. It’s ranked among the “most popular” Big Apple restaurants in the 2020 Zagat survey, which praised “new and exciting dishes” from chef Brad Steelman.

The lockdown put all of the glory in peril. O’Keeffe laments what he regards as poor political leadership at every level before and during the crisis.

“Any morning at breakfast at Pershing Square, I can pick three guys who can run the government better,” he said of the power clientele that congregates at his casual spot across from Grand Central Terminal.

“Pandemics are part of the history of mankind,” he said. “What the hell is this debate about closing down? Of course, government people still get paid every day. And rich people are okay. I’m not poor but I’m not a rich person.”

Unlike owners who are taking a wait-and-see attitude, O’Keeffe is eager to reopen as soon as possible. “We’d like to be open in some form by July,” he said last week. On Thursday, Gov. Andrew Cuomo announced that New York City restaurants could begin outdoor service as part of the reopening’s phase two, which could start as early as June 22.

O’Keeffe’s mood was short of elation, but, “It makes me happier,” he said. “It’s always better when they’re making progress.”

Like every owner, he’s struggling to deal with lost revenue during the lockdown. “I was just with my controller discussing how to pay people back for cancelled parties who put down $15,000 and $20,000 checks,” he said.

Many such private gatherings were on the River Café’s small outdoor terrace — which is where O’Keeffe will have a mere 20-odd seats for as long as 100 indoor seats remain idle.

“Starting up again is a real puzzle,” he acknowledged. While it isn’t yet known what rules the state or city might impose, he said, “I really don’t want to open with waiters coming out with masks.” If they don’t need gloves, “I’ll have a manicurist come in and do their hands, so their hands are immaculate.”

His plans also include a more “flexible” four-course prix-fixe menu in place of the previous three-course menu, air-conditioning system upgrades to thwart any viruses and the return of his long-time front-of-the-house team, some of whom have worked there for decades. They include wine director Joseph Delissio, manager Scott Stamford, and beloved jazz pianist Dom Salvador, who’s tinkled River Café’s ivories for 41 years.

O’Keeffe isn’t quite as pessimistic as some owners who say they couldn’t survive a 50 percent capacity limit. “With 50 percent capacity we could just get by,” he said. “At least you’re training your staff” in the hope that sooner or later, places could go back to their original seating density.

But he chafes over the lawsuit. Like his fellow restaurateurs, he agreed to settle it despite believing he’d done nothing wrong because it cost less than a prolonged court fight would have.

He said the lawsuits “took everybody’s rainy-day funds away. My weekly payroll [for River Café and for his Water Club, Pershing Square and Liberty Warehouse] was over $300,000, and you can’t sustain that unless you have a huge rainy-day fund. It was removed from many places and given to attorneys.”

Even so, he said, “We’re prepared for any storm. This one was severe, but we’re opening up.”

He looks forward to welcoming regulars – among them, World Trade Center developer Larry Silverstein and his wife, Klara.

“Larry comes in to look at his big buildings in Manhattan,” O’Keeffe said with a laugh. “He’s a terrific guy. His wife has a great sense of humor.”

“They came in one night when it was foggy. I said, ‘Mrs. Silverstein, I’m sorry you can’t see your apartment. [The couple live atop the Four Seasons downtown hotel, which Silverstein built.] She said, ‘Yes, I can — I left the lights on.’ ”

![Spanish-language social distancing safety sticker on a concrete footpath stating 'Espere aquí' [Wait here]](https://commercialobserver.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2026/02/footprints-RF-GettyImages-1291244648-WEB.jpg?quality=80&w=355&h=285&crop=1)