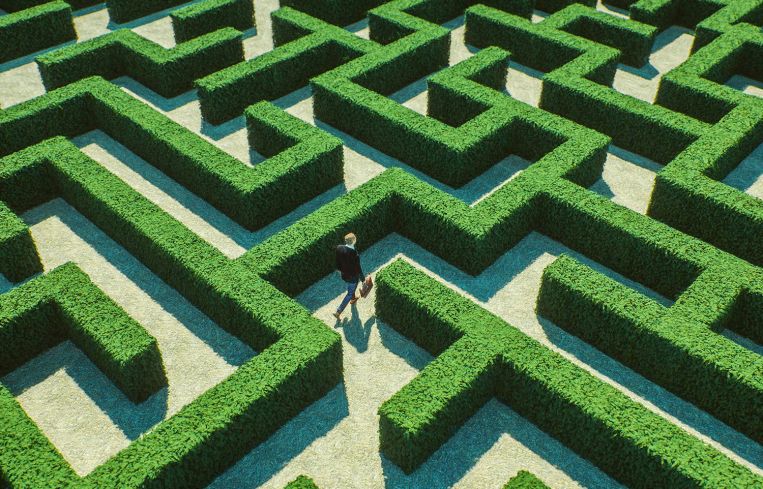

Navigating the Loan Workout Maze

From forbearance to hope notes, here’s what landlords need to know as they dust off the loan workout map.

By Sarika Gangar April 20, 2020 7:00 am

reprints

Spring cleaning this year, for many property owners, will mean a brushing off of the loan workout map that’s been gathering dust for much of the past decade.

Owners are seeing an abrupt halt to 10 years of rising property values, not to mention robust fundamentals, as the coronavirus pandemic forces the closure or curtailing of businesses across the nation. With tenants unwilling or unable to pay rent, and the recovery outlook uncertain, landlords are increasingly turning to lenders and servicers for mortgage relief or loan workouts. Together, the parties are navigating the maze of current troubles, pulling from past crises while responding to the singularity of the current one, to write the new workout playbook.

“As you can imagine, we were bombarded with a number of requests on the forbearance side,” said Mitchell Hunter, president for the Americas at Trimont Real Estate Advisors. “Hospitality has been really our main focus right now, and then retail. Those have seen a lot of requests coming in.”

Borrower requests for forbearance, or a temporary postponement in mortgage payments, have centered around a 90-day timeframe, a precedent that was set last month by the government on Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac loans. Trimont is sticking to forbearances ranging from 90 days to six months, despite seeing some requests that stretch past that timeframe.

“We’re not going past six months at this point,” Hunter said. “We’re in the mindset of, ‘Let’s wait and see.’ ”

Another relief request in recent weeks has been for lenders to reallocate reserves in lieu of the monthly payment, said Adam Fox, senior director of structured finance at Fitch Ratings. For retail assets, that can include reserves for tenant improvements or leasing commissions while hotels typically have reserves for FF&E, or furniture, fixtures, and equipment.

“There is an increase in requests to servicers to try and reallocate what they might have in reserves to pay debt service when it’s appropriate to keep the loan current,” Fox said. “That’s one of the things servicers will evaluate.”

The borrower behind a California retail portfolio backing a CMBS loan was able to negotiate such a deal in recent weeks, according to one New York-based debt advisor, who helped represent the borrower in negotiations. After paying the April rent out-of-pocket, the borrower negotiated a deal to use reserves to fund the monthly loan payments for the next three months, from May through July. The relief was negotiating with, and signed off by, the master service.

“Most of the time the master can be deputized to do it by the special servicer,” the advisor said. “It’s a slight modification, and it’s money that’s earmarked for CAPEX but it’s being used to keep the loan current.”

He added that the relief buys time for the economy to rightsize itself. “It postpones the pain for a while,” he said.

Trimont has also been evaluating how reserves are being held, Hunter said. For hotels, he noted the major chains sometimes allocate funds in their reserves for a property improvement plan (PIP), which they’ll likely put on hold for the rest of the year.

“We will ultimately look at reallocating [PIP funds] for operating costs, initially, and then potentially debt service,” he said. “For the most part, our concern is to keep the property at somewhat of an operational mode, recognizing that there is a lot of cost to start back up again.”

The firm has also recently seen borrower inquiries requesting deferrals at the contract rate, as opposed to the default rate, and requests for waivers of the LIBOR floor on floating-rate notes, Hunter said. It’s also discussing stretching out repayment periods following a deferral, for example, a three-month deferral followed by a six month period for the borrower to catch up on payments.

“When people get back on their feet, we don’t want to cut them off at their knees,” Hunter said. “We’re definitely taking a more practical approach to how the dollars ultimately get paid back.”

A borrower guide released by the Commercial Real Estate Finance Council, an industry trade group, advises owners to reach out to servicers in writing, providing such items as current financial statements and rent rolls, as well as their plans for the future of the property and the repayment of any forbearance.

Part of the struggle right now, for servicers, is deciding who to help.

“From the servicers’ perspective, it’s very much a triage mode and trying to digest all of the requests that are coming in and really identify those that are the most urgent,” Fox said. “And those are typically your businesses that are closed and really can’t make debt service payments.”

At Trimont, the firm is digging into properties’ past performance, including any previous excess cash flow, and the sponsorship in determining how to handle requests, Hunter said. “It’s more of a look back than it is a look forward right now for us,” he said.

He pointed to a hypothetical performing property, where say the sponsor has pocketed millions in excess cash flow. “Probably, we’re not going to forgive too much on the April payment,” Hunter said. “And I think most lenders took that approach: We expect you to make that April 1 payment, and then let’s see where we are in May and June.”

“A real problem”

While short-term relief like a 90-day forbearance may provide some breathing room, it might not be enough for some properties to weather the storm, Fox said.

“Realistically, a lot of these assets are probably going to need longer than 90 days,” he said. “Specifically because these are operating businesses, and you’re going to have a delay in the return of consumer spending and consumer confidence before they’re going back to hotels and retail centers.”

A prolonged shutdown or a deep recession could prompt defaults and transfers into special servicing, triggering formal workouts. (On short-term relief requests, a borrower can sometimes exercise a “consent non-transfer event” to negotiate with the master servicer and avoid the transfer to special servicing and the accompanying fee, Fox noted.)

Fitch is already projecting a spike in commercial mortgage-backed securities (CMBS) delinquencies, from last month’s 1.31 percent to between 8.25 and 8.75 percent by September, that would rival the peak set following the 2007-2009 Great Recession. Delinquencies in hotel and retail are expected to hit 30 percent and 20 percent, respectively.

Asset types that could see increasing stress, as they deal with dwindling rents or perhaps a need to refinance in shaky markets, include student housing, apartments with high concentrations of hourly wage employees or exposure to the oil and gas industry, single-tenant offices leased to non-credit worthy tenants, and offices with high exposure to coworking, according to an April 9 Fitch report.

“It’s very much a tenant-based story,” Fox said. “It’s really where the tenants are. So areas like Las Vegas and Orlando, where you have things that are dependent on tourism, they’re going to be among some of the hardest hit.”

Investors are watching for details on forbearance requests, delinquencies and special servicing transfers to gauge the depth of the economic pain in the market, said Manus Clancy, senior managing director at Trepp, a CMBS data and analytics firm. Specifically, they were holding their breath last week as the CMBS trusts released their monthly remit reports detailing March payment activity and borrower requests.

The mood holds similarities to the eve of the Great Recession, he said, recalling a securitization conference where antsy investors were awaiting the release of subprime bond remits.

“People were waiting for their Blackberries to light up to see what the numbers were, because people were so alarmed by it; that was kind of our first tell that this was a real problem,” Clancy said. “Here, now, it feels like everybody’s waiting to see what the watchlist comments say this month, [and] the percentage of loans transferring to special servicing.”

Let’s work it out

During the last crisis, non-performing loans often saw modifications to loan terms ranging from the maturity date to the interest rate and beyond, Clancy said.

The length of maturity extensions were all over the map, with many landing somewhere in the 24-month range, though some loans saw relatively long extensions of three to five years, he said. Some notes also saw significant reductions in their interest rate. “Rate relief rarely went to zero [percent], but sometimes it went to 1 percent,” Clancy said. “And a lot of times it was, ‘We’re gonna give you 1 percent for two years, and then it’ll go to 2 percent, to 3 percent over a course of time.’ We’ll build it back up.”

Other terms that were often fair game include the waiver of amortization payments and the release of, or the waiver on funding, reserve accounts.

In the previous crisis, these modification talks were often “dual-tracked” with a legal action to foreclose on the asset. In this current wave, servicers are likely to continue to pursue legal action, despite the current backlog in courts, given it’s part of their fiduciary duty, Fox said.

One unique workout option during the Great Recession, and one that execs said was typically pulled out at the 11th hour, was the A/B note split, also known as a loan bifurcation or a “hope note.” The technique, which typically rests on a property’s current appraised value, motivates owners to invest in an underwater property while splitting the upside on any future rise in valuation. Executives noted the option often functioned as a last resort after other workout options fell through.

Special servicer CWCapital used the technique in the 2016 workout of the 37-story 131 South Dearborn office in Chicago, according to Trepp data. In documenting the workout, the servicer cited the risk of the property turning into a “zombie building” after it was hammered by major tenant losses. The property had seen its valuation plunge from $590 million to $415.6 million by the time of the workout.

The property’s $472 million loan, which was split evenly between two CMBS deals issued in 2006 and 2007, was bifurcated into $400 million of A notes and $72 million of B notes. The modification, which also included a four-year maturity extension and an interest rate reduction, hinged on new owners Angelo Gordon, Hines and Dearborn Capital promising to invest at least $27 million into the property.

When it comes time to pay back the debt, proceeds will go towards the A-note, followed by repayment of the owners’ equity investment, followed by a 50/50 split between the owners and the B-note.

“The modification is structured such that the borrower invests the capital and the [CMBS] trust shares in the upside of the value creation,” modification documents stated.

The loan, which comes due in December, is currently back on the servicer watchlist due to weak financials.

Executives are quick to note the myriad differences between the Great Recession and the current predicament driven by the coronavirus pandemic. Today’s ownership is facing a sudden and complete shutdown in economic activity, broad socio-economic pain, and the sense that nobody has been spared from the wreckage.

“In 2007, we had years for loans to default and be worked out,” Fox said. “Here, we are seeing what was played out in years, being played out in weeks.”

And there’s a realization that many landlords have been left in the lurch.

“For the most part, [servicers] are very aware of the fact that this is just a situation that no one can be blamed for,” Hunter said.