NYC’s Property Tax Reforms Are Pitting Homeowners Against Renters

By Rebecca Baird-Remba March 10, 2020 2:22 pm

reprints

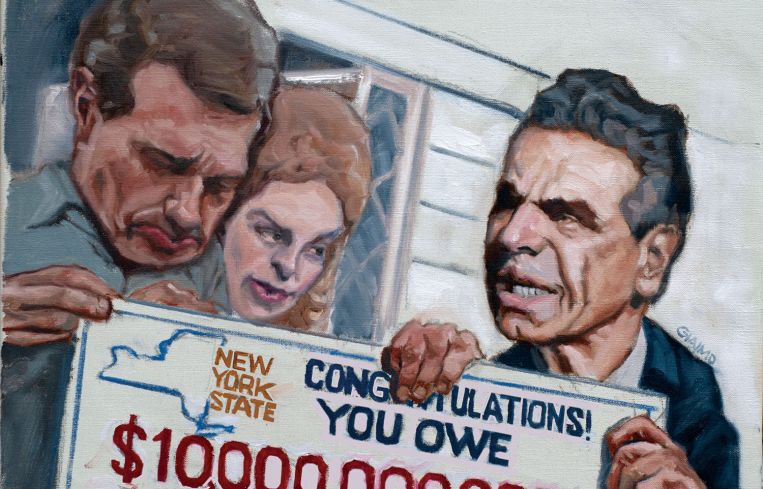

New York City hopes to reform its byzantine property tax system, but the changes it has pitched so far will mostly benefit the owners of one- to three-family homes, rather than renters and commercial building owners. While many homeowners will be thrilled to get lower tax bills, real estate groups, the NAACP and several other activist and good-government groups feel that the proposals don’t address the biggest problems in the city’s tax system.

A property tax commission convened by Mayor Bill de Blasio released its initial set of proposals at the end of January after two years of public hearings and debate. The report only addressed inequities in one part of the tax system — the part that affected the owners of homes, condos and co-ops.

When the mayor convened the commission in 2018, he was responding to a lawsuit filed by a coalition called Tax Equity Now New York (TENNY), which included the Rent Stabilization Association, a landlord group, along with the Citizens Budget Commission, the Regional Plan Association, the NAACP, The Black Institute, Citizens Housing and Planning Council and several New York City development firms like RXR and the Durst Organization. The state Supreme Court recently dismissed the suit, but TENNY plans to appeal to the Court of Appeals. The group pointed to a few major issues in the city’s complex tax system, which is set up to tax homeowners — particularly owners of high-value homes — at lower rates than other kinds of properties.

Caps that limit how much the assessed value of a home can increase annually have favored owners of homes in neighborhoods with fast rising property values, who often end up paying lower taxes than homeowners in parts of the city with slower economic growth. The city’s confusing rules mean that the owner of a modest house in Canarsie or the North Shore of Staten Island can end up shelling out more in taxes than the owner of a two-family brownstone in Park Slope. Lower income homeowners — many of whom are black, Latino or first-generation immigrants — are often the ones shouldering those tax burdens.

“Homeowners in majority minority districts pay way more than they should,” said Martha Stark, a former city finance commissioner under Mayor Michael Bloomberg and the policy director for TENNY, the group behind the property tax lawsuit. “People have known this for decades, and the legislature has known this for decades and has done nothing. The only reason there’s any property tax commission is because of our lawsuit.”

Meanwhile, the city taxes condominiums and co-ops based on the values of comparable rental properties, which often results in the city dramatically undervaluing expensive apartments. Tax analysts note that there are no rentals comparable to a $50 million condo in One57, and condos often have tax breaks that further reduce property taxes for their owners. Plus, the city often uses older rent-stabilized buildings to determine the value of co-ops, even though co-ops in affluent parts of the city frequently sell for seven figures.

“On average, the Department of Finance is capturing one-third to one-quarter of the tax value [of co-ops and condos],” said Ana Champeny, the director of city studies at the Citizens Budget Commission. “If you have a half-a-million-dollar co-op right now, your DOF value is probably on the order of $100,000; under the new system it will rise to $500,000. If you have a $10 million condo it’s probably [valued at] $1.4 million now, and it would rise to $10 million [under the new proposals].”

The mayor’s tax commission has recommended axing these rules, moving condos and co-ops into the same class as one- to three-family homes, and assessing all of these properties at fair market value. Eliminating the assessment caps and using comparable sales to determine how a home should be valued will help bring New York City’s tax system in line with existing legal precedent, which states that properties should be assessed at fair market value.

The commission also recommended a homestead exemption and a circuit breaker tax credit, both of which would help lower property taxes for lower- and middle-class homeowners. State Senator Andrew Gounardes of Bay Ridge recently proposed a bill for a circuit breaker that would provide a tax refund to homeowners who earn less than $200,000 and pay at least 2 percent of their income or more in property taxes. Those earning less than $100,000 would receive a 15 percent refund, and the refund amount drops to between ten and 5 percent for those in income brackets between $100,000 and $200,000.

The state legislature would have to approve any major changes to the city tax code, but it’s unclear when or even if state legislators would be willing to approve a property tax overhaul. A tax reform bill is also unlikely to make it to the floor of the state senate or assembly before the end of this year’s session, which means that the proposal won’t be passed until 2021 at the earliest.

The mayor has said he would push to reform the property tax system before he leaves office next year even though the taxes on his two Park Slope homes would rise significantly. State Senator Brian Benjamin, who represents upper Manhattan, also recently proposed a more modest tax reform bill that would remove the assessment cap for homes, condos and co-ops once they are sold.

Tax relief may be in the cards for home owners, but not for many renters, who are unknowingly paying at least a third of their rent towards taxes, according to tax policy researchers. Multifamily rental buildings are taxed at higher rates than homes, co-ops and condos, which means that renters are, indirectly, shouldering a larger share of the city’s property tax burden. The tax commission’s report shows that large rentals are taxed at nearly twice the rate of one- to three-family homes and co-ops and at 2.5 times the rate of condos.

“Many renters tend to be people of color,” said Stark. “There just tends to be a lot of overlap between people who are low income, renters and people of color.”

She added that “taxes make up about 40 percent of the rent that people pay.” The current assessment system significantly undervalues condos and co-ops, and “You know who’s footing that bill? The owners of rental housing. The report leaves renters with the same burden they’ve been bearing for 40 years. I think that’s a fundamental flaw in the report.”

Under the city’s current tax system, one- to three-family homes are categorized as Class 1, while rentals, condos and co-ops are in Class 2. Class 3 includes utility properties, like electric and phone company buildings, and Class 4 is all other commercial properties. In 2019, Class 4 accounted for the largest share — 42 percent — of property taxes paid to the city, while rental buildings made up 19 percent, according to the tax commission report. Class 1 — in other words homeowners — paid just 15 percent of the tax share on buildings that comprise 48 percent of the assessed property value in New York City. Across all properties, the city levied $28.3 billion in taxes for fiscal year 2019.

If the state adopts the recommendations from the mayor’s commission, co-ops and condos and small rental buildings with up to 10 units will be moved into Class 1 with one- to three-family homes. (Small rental buildings have also benefited from caps on assessed value and from not being required to file income and expense reports with the city’s finance department.) When de Blasio appointed the commission, he informed them that any changes to the property tax system must be revenue-neutral — meaning that the amount of taxes the city collects must remain the same overall. So, it set out to lower taxes for the large number of homeowners who are now being taxed at unfairly high rates by raising taxes on undervalued home, condo and co-op owners in wealthier areas. Since the city’s aim is to lower taxes for homeowners, large rental building owners and their tenants will continue to pay higher taxes.

“The dollars you have available to redistribute [to property owners] go further in Class 1 than if you’re dealing with both Class 1 and the rental properties,” said George Sweeting, a deputy director at the city’s Independent Budget Office. “If you’re only doing it in Class 1, everyone on Staten Island gets a tax reduction. But if you’re redistributing across Class 1 and Class 2, some people on Staten Island get a reduction but it’s much less uniform.”

Mark Willis, a senior policy fellow at New York University’s Furman Center, argued that lowering property taxes for large rental buildings would not mean lower rents in the short term.

“In the long run we might get more rental property and that would lower pressure on rents overall, but in the short term the market rent is the market rent,” said Willis. “If property taxes were too high — pre-rent-reform — then why would property prices go up? If you think that [taxes] are squeezing landlords and making their business unprofitable, I’d think again.”