Cap Rates Are in a Vicious Tug-of-War

By Dan Gorczycki October 4, 2019 12:50 pm

reprints

“And now the die is shaken, now the die must fall.” — Jerry Garcia

For as long as capitalization rates have been calculated in real estate, there has been an ongoing debate as to what they should be, given interest rates, cost of capital, returns on alternative investments, supply and demand constraints, tax incentives, et cetera.

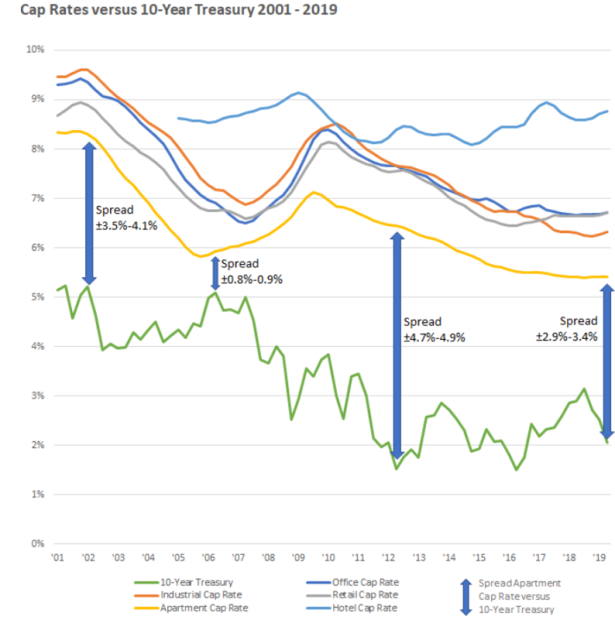

When I broke into the business in the 1980s, developers were building because they, in many cases, received five-to-one tax write-offs, so the fundamentals and returns were almost inconsequential. The Tax Reform Act of 1986, which did away with much of these abused tax-sheltering practices, changed all of that. Cap rates became normalized and there was a proven correlation between government and investment grade bond interest rates and real estate unleveraged yields. Using multifamily as an example, cap rates on Class A product were approximately 300 to 400 basis points higher than the 10-year Treasury nationally. This spread broke down at the peak of the cycle in 2006, when cap rates were only 100 bps over the 10-year Treasury, as investors bid up prices to unsustainable levels. The 2008-2009 downturn then caused the pendulum to swing the other way, with spreads peaking at more than 5 percent in 2012. Today, we are back to 3 percent or so as Treasury yields have plummeted. However, there is now a very wide disparity between property types and sub-markets. Class A apartments in rent-regulated buildings had been at 3 percent cap rates before the recent rent regulation changes, which will cap their upside. But they rose almost 2 percent overnight, although there haven’t been any notable trades to explain that rise. Why else have these traditional benchmarks come unstuck, and where do we go from here?

There is a vicious tug-of-war. Cap rates have external factors pushing them up — mostly fundamentals — and other factors pushing them down. (Largely interest rates and flight to hard assets.) For starters, the flatter yield curve has caused all kinds of unforeseen consequences. For institutions with long-term money to put out, any alternative is better than buying sub-2 percent Treasurys. If interest rates were to rise, those current Treasury buyers would have a capital loss. The bidding up of Class A real estate is a better alternative and is one of the primary reasons cap rates haven’t risen even though fundamentals, in many markets, have deteriorated and foreign investment has mostly dried up. Being able to leverage those assets with sub-4 percent mortgages only exacerbates the situation, causing cap rates to further compress.

It’s important to note that cap rates are not a true indicator of value. They’re only a snapshot, with many other external factors also weighing in. Class B malls sometimes trade at 15 percent cap rates. Whether their cash flow will still be around two or three years from now is a serious concern. Nationally, Class A apartments might trade at a 5 percent cap rate because the supply and demand constraints in that asset class have downside protection for the rents achieved.

So where are we now? As long as interest rates stay at or near current levels, cap rates aren’t going up sharply, barring a deep recession, anytime soon. The true test will be when interest rates someday spike due to an exogenous event. When repo rates jumped in September, was that a warning sign? Will institutions audible from real estate back to fixed-income instruments? Will cap rates rise simply because financing is more expensive? The answer to all three questions is likely yes. But to what degree? As the accompanying chart illustrates, there is definitely a correlation between cap rates and interest rates: Only the peak of 2005 and 2006 defied it.

We know how that turned out.

Dan Gorczycki is a senior director in the debt, joint venture and structuring group for Avison Young.