Will Venture Capital Venture Into Opportunity Zones?

By Chava Gourarie July 17, 2019 10:30 am

reprints

The newest version of the opportunity zones program was supposed to be a game-changer for venture capital.

In April, the IRS released updated rules for the program, which clarified how operating businesses can qualify for opportunity zone benefits. The new guidelines seemed to indicate that start-ups made the cut. That was supposed to unleash a flurry of activity from venture capital firms and start-ups to join the fun the real estate industry was having.

“If you live in Silicon Valley, you should be selling your house, because every start-up is going to be moving to an opportunity zone,” EJF Capital CEO Manny Friedman told a Los Angeles audience at the Milken Institute Global Conference in April. “The advantages are so mind-boggling.”

Friedman’s own firm is raising a $500 million real estate opportunity zone fund.

However, we have yet to see the same hype that overtook the real estate industry among venture capital types. There’s certainly interest, with a handful of funds launching and start-ups making moves, but we’re seeing very few significant plays by the movers and shakers of the industry.

A key issue is that the opportunity zone program was designed for patient capital, since its most dramatic benefit can only be captured after 10 years. The program offers deferral of taxes on capital gains invested in opportunity zones until 2026, a reduction in taxes if the investments remain in place for five or seven years, and elimination of taxes if the investment is held for 10 years.

Venture capital, however, tends to be flexible and move quickly, said Cary Zimmerman, a securities lawyer with Kohrman, Jackson & Krantz. Start-up investors are used to a three-to-seven-year horizon, and the best-case scenario is if the company is offered an exit within that time frame. The program does offer an option for investors to reinvest any interim capital gains within 12 months of the return, but that would still require a shift in the traditional venture model, said Zimmerman.

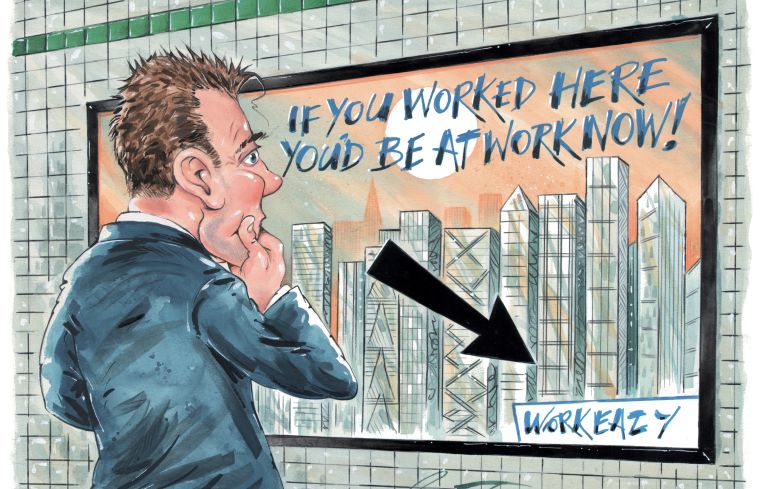

For many, that’s not a fatal flaw, even though it is an issue that needs to be addressed. A handful of funds, particularly those already engaged in opportunity zone areas, have launched, and many others are exploring their options. On the start-up side, some have considered changing their addresses, and coworking communities have begun to highlight which of their locations are in opportunity zones.

Compound, a Brooklyn-based start-up focused on real estate investment, is planning to move its operations to a location in an opportunity zone. The new regulations are “transformative for how start-ups will get funded,” the CEO, Janine Yorio, said.

Considering how much capital was poured into the real estate portion of the program, “it’s reasonable to assume that some portion of that capital would be interested in investing in small businesses and start-ups, because they have a much higher potential for returns,” she said. “My hypothesis is that once the market wakes up to those benefits, businesses that are based in those opportunity zones are going to find it easier to raise funds.”

The opportunity zone program, introduced by the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, was designed to incentivize investment into low-income areas of the country by offering tax breaks on capital gains invested in designated zones—either into real estate or into operating businesses. The original legislation was vague, so it wasn’t until October 2018, when the IRS published guidelines governing the program, that it began to take off.

One thing that remained unclear was the definition of a “qualifying operating business.” According to the October guidance, a business had to derive 50 percent of its gross income from within an opportunity zone—a difficult test for any software or online company with a national or global clientele. The April guidelines provided three ways for a company to pass the 50-percent test: The total hours worked by the company’s staff in the opportunity zone exceeded 50 percent of the company’s work hours; 50 percent of the company’s payroll went to employees working within the opportunity zone; or that work done in the opportunity zone generated 50 percent of the company’s revenue. That opened the door for many more companies to qualify.

Launch Pad, a coworking space and incubator based in New Orleans, La., is optimistic about the way the program will change investment. Run by husband-and-wife duo Chris Schultz and Anne Driscoll, Launch Pad has five operational locations, four already in opportunity zones, with plans to open a total of 25 locations by 2021. They have also invested $500,000 as angel investors in nine Launch Pad companies since 2009.

“I joke that we’re the O.G. O.Z.,” said Driscoll. “Basically, we’re betting the farm on the fact that there are great companies being built outside of New York.”

Launch Pad’s mission has always been to invest in underserved communities, and the owners expect the regulations will accelerate their vision.

“The regs came out in our favor in a really positive way. It’s really going to drum up interest from investors to get off their real estate butts and focus on Q.O.Z.B.s (qualified opportunity zone businesses),” Driscoll said.

Markeze Bryant, who operates a firm called CapitalStreams out of East Oakland, Calif., and works with the state organization CalOZ, is also interested in serving underserved communities. Bryant has been looking for ways to move capital into local businesses since the tax legislation first passed.

“When you read the original report on this, all they’re talking about is job creation and business starts,” Bryant said. “I was confused as to why this had shifted into some sort of real estate incentive.”

The key challenge facing venture capital is that the parameters of the opportunity zone program are not exactly aligned with traditional venture capital, which tends to be flexible and move quickly. The primary benefit of the program is the 10-year option, which eliminates all taxes on both the initial capital gains investment, and on any capital gains earned during the 10-year period.

Neither Bryant nor the Launch Pad duo were concerned about that issue, but they have differing views as to where the capital would be best placed. Launch Pad’s Schultz said he’s looking for capital to flow in the very early stages of companies, in the seed and angel rounds, while Bryant said his focus is on later-stage growth companies. Bryant pointed out that many companies in the later stages are looking to grow rather than exit.

“These are businesses that have a proven product, are ready to scale and add a bunch of jobs,” said Bryant.

One company he’s working with, a healthcare company that employs 30 people and has close to $5 million in revenue, is looking to raise up to $5 million in equity. “They want to scale and double their employee count,” Bryant said. “And they want to move in to an opportunity zone to do that.”

Bryant and Launch Pad also said that they can act as intermediaries for bigger companies or individuals with capital to deploy, since they’re familiar with the areas they work in.

Zach Aarons, the co-founder of venture capital firm MetaProp, said that, in theory, he’d expect to see the capital begin to flow, but in practice, he hasn’t yet. “I have yet to see venture capital opportunity zone funds, or even deals, that [aren’t] connected in any way to real estate,” he said.

However, he can see the appeal. “If I was starting a business from scratch today, I would open it in the Navy Yard, because I’d have nothing to lose,” Aarons said. Worst case, the new business is in a start-up hub and urban center and, “best case, I’ve just unlocked a whole new kind of capital.”

Compound’s Yorio, whose company has started a database for qualified opportunity zone businesses in order to raise awareness about the program’s potential, said that’s due to the early stage of the game.

“The gold rush hasn’t started yet,” she said.

This story has also been updated to reflect that Launch Pad has invested $500,000 in companies that work out of its locations, not $5.6 million as previously stated. The story has also been updated to reflect that the healthcare company working with Bryant’s CapitalStreams is seeking to raise up to $5 million in equity, and has not raised $50 million, as previously stated.