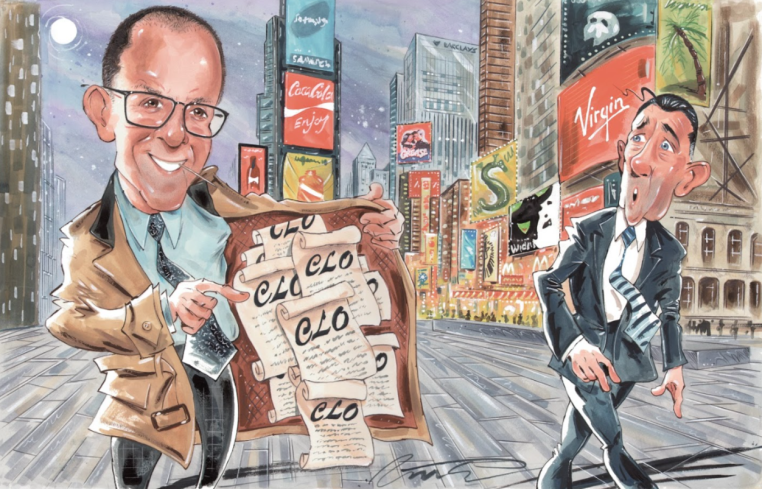

Power 50 Lenders Learned to Stop Worrying and Love CLOs Last Year

By Matt Grossman April 2, 2019 11:00 am

reprints

LoanCore, the real estate debt investment shop backed by the Canadian Pension Plan Investment Board and GIC, would have been a strong contender to make Commercial Observer’s Power 50 list any year, what with its national presence and impressive lending volumes. But one feat all but guaranteed the lender the highest-ranked spot among newcomers on our list.

Over the summer, LoanCore priced a $1.05 billion commercial real estate collateralized loan obligation—an achievement that demonstrated that the ambitious loan shop had its finger squarely on the pulse of the industry.

Not since before the financial crisis had CLOs—which pool, slice up and resell loans on non-stabilized real estate—played such a prominent role in national lending markets as they did last year.

Issuance rose to $13.9 billion in 2018 over 25 deals. Granted, that’s a puny figure next to 2018’s $77 billion CMBS conduit trade, but the CLO sector grew 80 percent over 2017’s $7.7 billion tally, and has left its totals from just two years ago in the dust. (In 2016, issuance was less than $2.5 billion.)

“I think you’ll see a really active CLO pipeline [in 2018],” Wells Fargo’s Kara McShane predicted for CO last year—turning out to be right on the money.

Richard Jones, a Dechert attorney and eminence grise in the world of commercial real estate finance law, has cheered on the rehabilitation of CLOs’ tawdry image following the financial crisis. In a recent editorial in Lexology, a legal blog, he likened the shift in CLOs’ estimation to the turnaround that would occur were Pete Rose (who blew his reputation as one of the greatest players in baseball after getting caught in a gambling scandal), inducted into the major leagues’ Hall of Fame.

If fans can forgive Charlie Hustle for betting against his own team—a sentiment that has gathered momentum over the years—”the full restoration of the reputation of the CRE CLO cannot be far behind,” Jones declared.

Because CLO issuers hold the entirety of the first-loss position in the capital stack, the lawyer argued, the securities do a good job of mating managers’ incentives with those of investors, a trick that real estate finance rarely manages so cleanly.

What’s more, market conditions meant that the transactions had the wind at their back last year.

“The market tightened from a pricing perspective,” Chris Herron, a managing director at Iron Hound, explained. “The CLO players were able to tighten their pricing, and the market followed.”

LoanCore wasn’t the only Power 50 honoree to ride CLO business to higher slots in our rankings this time around. TPG Real Estate Finance Trust, the shop that was the biggest single issuer of the securities in 2018, jumped six spots on the list, landing its CEO, Greta Guggenheim, at 39.

“Our first CLO [of the year] occurred in February 2018, [and] at the time we did it, it was the tightest pricing of any issuer,” Guggenheim said. “That enabled us to go out and win more business, because our cost of funds was attractive.”

In October 2018, Greystone (which also leaped six spots) launched the first CLO backed solely by senior-housing facilities, in a deal worth $300 million.

“Historically, we’ve used bank, warehouse and repo lines to lever the business,” Greystone vice president Mark Jarrell told Senior Housing News. “The CLO gives us diversity of financing sources for the business.”

Filling out an odd pattern, Barclays, another key player in the space, also saw its representative, Larry Kravetz, jump six spots on this year’s list. The firm’s executives aver that with appropriate caution taken, securitizing transitional loans can be a sound credit endeavor.

KKR’s real estate credit business, KREF, led by Power 50 honorees Chris Lee and Matt Salem, got in on the fun, too. Last November, it issued a CLO valued at an even $1 billion, a managed deal (which means that KKR can rearrange the underlying loans after securitization) with a two-year reinvestment period.

Legacy financial institutions—including many ranked highly on this year’s list—also played a key part in the surge as providers of the capital needed to fuel CLO lending. Wells Fargo was tops in the part, according to statistics from Commercial Mortgage Alert, responsible for powering $5.16 billion worth of deals. J.P. Morgan Chase wasn’t far behind at $4 billion, and Goldman Sachs had a nice taste of the action as well, supporting transactions with credit worth $1.89 billion.

And though this year’s top banana, Blackstone, didn’t issue CLOs in 2018, it was a notable cheerleader the year before, when it launched a billion-dollar CLO that was the biggest in history at the time.

Still, it’s not clear that recent success has launched the sector on an unbounded upward trajectory. Last year was bright overall, but the deals slowed down notably towards the end of the year, when market turmoil threw benchmark interest rates’ gentle upward course into uncertainty for the first time in years.

Spreads widened as a result, making it harder for landlords and lenders to see eye-to-eye on financing costs. Panelists at Information Management Network’s CLO conference in New York City last month agreed unanimously that the market would at best be flat this year while players wait for the interest-rate picture—and the economy more broadly—to crystallize, according to a Kroll Bond Rating Agency report about the event.

CLOs are still much more thinly traded than other sorts of mortgage bonds, KBRA noted, which makes investors wary. The debt often envisions borrowers’ completing tricky business plans, which could be jeopardized if the real estate cycle takes a turn. No one wants to be left holding the hot potato.