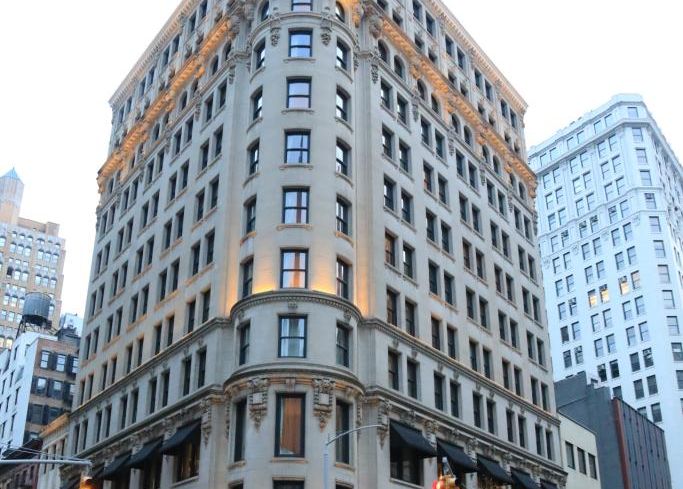

NoMad Hotel Ownership Failed to Pay $140M in Debt Last Year Amid Lawsuits

A legal battle over its ground lease has coincided with the hotel’s missed payments

By Mack Burke and Matt Grossman April 18, 2019 6:00 pm

reprints

The owners of Manhattan’s NoMad Hotel—now set to be sold at a Uniform Commercial Code, or UCC, foreclosure auction in June—failed to make good on more than $100 million owed to lenders and equity investors starting late last year, according to documents in state and federal lawsuits.

But the hotel’s ownership counters that the lawsuits may be nothing more than a cunning ploy by the building’s landlord to gain financial leverage.

Andrew Zobler, who helped develop the property with GFI Capital’s Allen Gross, owns the hotel at 1710 Broadway under a ground-lease structure, which means that he has property rights for the hotel building but leases the ground under it from another entity, the Haddad Organization.

A subsidiary of Zobler’s top-level ownership stake, called 1710 Broadway Associates, borrowed $140 million against the hotel in 2015: a $105 million senior mortgage from Bank of America, and a $35 million mezzanine loan from Colony Capital.

Those mortgages came due on Dec. 10, 2018, but for reasons that are not yet clear, Zobler’s company failed to pay back the debt.

A Ground Lease Gone Bad?

In the state court lawsuit first filed on March 7, Haddad Organization submitted a letter from Bank of America in which the lender complained that 1710 Broadway Associates hadn’t paid what it owed. Other evidence submitted in court proceedings show that Colony wasn’t paid back on time, either.

The default was surprising because by all accounts, the hotel was considered a rock-solid asset.

Since 2015, the hotel’s gross revenue climbed $2.5 million per year, on average, through 2018, according to information obtained by CO. The asset’s net operating income (NOI) increased on average by just over $1 million per year, over the same period.

“It’s one of the stronger performers in the city in the independent boutique sector,” said Sean Hennessy, a hotel analyst at Lodging Advisors who was not involved with the property. “From everything I know, the hotel is a stellar financial performer.”

Regardless, the hotel appears to be on track to be sold off in a UCC foreclosure auction on June 6, as CO reported earlier this week. The proceeding, initiated by Colony, is one of the quickest ways for a mezzanine lender to assert its rights to seize the collateral. Unlike a foreclosure auction, it sells off not the property, but the business that operates there.

The substance of Haddad’s lawsuit revolves around 1710 Broadway Associates’ alleged failure to resolve building-code violations, like defective facade work on one portion of the building’s street frontage. But in a letter dated Feb. 25, 1710 Broadway Associates’ lawyer argued that the violations were minor and easily fixed. The lawyer also submitted evidence showing that many of them had been fixed. Instead, he claimed, the lawsuit was a nefarious effort to evict the tenant.

“It is clear from the ‘defaults’ alluded to that [the legal complaint]…is nothing more than a transparent attempt to harass and intimidate” 1710 Broadway Associates, the lawyer, Howard Shapiro, wrote. “It is laughable that you would seek to terminate a 99-year ground lease by reason of, among other things, a violation cited in 2010, or one arising from ‘metal, glass and plastic mixed with paper’ ”—a reference to a New York City Department of Sanitation violation that the NoMad operators received for sorting trash incorrectly. Nonetheless, 1710 Broadway Associates dutifully submitted evidence showing that the sanitation complaints had been rectified.

Why would Haddad want to banish a successful business? The lawsuit doesn’t provide ready answers, but the affidavit of one 1710 Broadway executive, Joshua Babbitt, points to a possible explanation. When the ground lease was signed a decade ago, Babbitt said, the blocks around the hotel were better known as a sleazy area to buy counterfeit designer goods. As a result, the economics behind the ground lease that Haddad signed 10 years ago are likely very different from terms it would agree to today.

In the state-court lawsuit, 1710 Associates lawyers accuse Haddad of being on the lookout for a reason to stir up a legal brouhaha. After all, the stakes were high for the borrower. Haddad’s lawyers made sure that Bank of America (the senior lender) and Colony Financial (the mezzanine lender) received copies of each new filing, which couldn’t have helped 1710 Associates’ ability to refinance its expiring debt late last year. At one point, a lawyer for 1710 Associates complained that Haddad was distributing court filings too widely.

Elsewhere, Shapiro, one of 1710’s attorneys, directly accused Haddad of using the litigation to get out of a bad business deal.

“It is abundantly clear that the landlord is unhappy with the economic deal reached more than 11 years ago…and through this default notice is attempting to extort concessions from the tenant parties to improve that deal,” Shapiro wrote in a letter that was included in the court filings.

In a court hearing in April, even the judge presiding over the case seemed to accept 1710’s argument about Haddad’s motivation, according to a transcript.

“This lease was entered into back in 2008. We were obviously in a very different world in 2008 than we are today,” Steven Sinatra, another lawyer for 1710, told the judge, Andrew Borrok. “Would it surprise you to learn that they’re not happy with the distributions they’re receiving?”

“I got that,” Borrok replied. “I can read the tea leaves.”

But Haddad’s lawyer, Cecelia Fanelli, has insisted that the landlord is only trying to get the hotel to fix building-code violations.

“The primary violation remains uncured,” Fanelli wrote in one filing to the judge. “Mr. Shapiro fails to explain why the Department of Buildings has an open facade violation and is fining the landlord each month.”

Lenders Say No to Lawsuits

Lenders surveyed by Commercial Observer about the situation indicated that Haddad’s tactics could have made it somewhat more difficult for the hotel to get refinancing.

Toby Cobb, a cofounder of 3650 REIT, a specialized commercial real estate lender, emphasized that he was not familiar with the specifics of the NoMad Hotel’s circumstances, but in general, he said, litigation would drastically pare down the field of lenders with the expertise necessary to make a loan.

“In a situation like this, you might see a firm like ours being willing to take on the underwriting—and, frankly, probably get paid for it,” Cobb said, noting that 3650’s executive team had prior work experience at other companies in which they worked out complex, distressed loans related to hotels in particular. “But a lender that doesn’t own real estate, like a bank, or a lender without workout experience, like a bank, might shy away.”

What’s more, he said, the situation could close off the availability of other executions, like securitization.

“If you said this [asset] was going into a standard [CMBS] conduit, that would be very, very unusual,” Cobb said.

One veteran lending executive at a prominent New York-based company, who requested not to be named, told CO that ground-lease litigation would certainly give his firm pause before extending credit—regardless of the collateral’s financial fundamentals.

“As a lender, this situation would require a deep understanding of the matter and reason for default before extending credit,” the executive said. “It would definitely grab our attention, and it could potentially be a showstopper.”

Federal Litigation, as Well

Meanwhile, a third investor has also argued in new court documents that hotel ownership failed to meet financial obligations starting late last year. Chevron, a giant energy concern, invested equity in the hotel in 2009, when it was being developed. Part of their equity deal, Chevron claims, included a unilateral option to sell back its ownership share to guarantors GFI Capital and Square Mile Capital Management for around $5 million starting in November 2018.

Chevron claims in a federal lawsuit filed last week that it tried to take advantage of that option last November, but that the guarantors reneged on their end of the deal. A Square Mile spokesman declined to comment, and representatives for GFI did not immediately respond.

On the other hand, a lawyer’s description of the hotel’s ownership structure, written in 2015, appears to show that GFI and Square Mile were no longer responsible for ensuring Chevron’s put option, having passed that responsibility along to the NoMad Hotel’s new owners. It’s unclear how that document fits in to Chevron’s argument. A lawyer for Chevron in the case did not immediately respond to an email and a phone call.

In an email, GFI’s Gross contended that his company has been long removed from any involvement with the hotel. “We were bought out 2012. It’s been seven years,” Gross wrote.

Lawyers and representatives for the parties to the litigation—1710 Associates, Haddad Organization, Bank of America, Colony Financial, and Chevron—did not respond to inquiries.

The fact that a date for the UCC auction has been set does not make the sale inevitable. 1710 Associates could delay the proceeding by asking for an injunction or by filling for bankruptcy. Or, it could remain in control of the property by finding a way to pay back the $35 million mezzanine loan.