REIT My Lips: Seeing Opportunity, Office Trusts Elbow for Position

By Matt Grossman January 16, 2019 1:00 pm

reprints

December 2018 may have been one of the most chaotic months in recent memory for the stock market. But with strong deal flow and no signs of stirring in delinquency rates, commercial real estate seemed to escape almost entirely unscathed.

Almost. As last year came to a close, real estate investment trusts were being revalued at a rapid clip.

Few big names were immune. Boston Properties? Its shares were down more than 17 percent in December. Simon Property Group? Off 10 percent, and ditto for AvalonBay Communities. Columbia Property Trust’s stock fell by a similar proportion, and though Toll Brothers managed to end the month flat, it was a hair-raising ride, with shares dropping nearly 8 percent and then bouncing back overnight.

A roller-coaster ride? Perhaps. But to Tom Catherwood, a REIT analyst at BTIG, it could be just the thrill public real estate investors were waiting for—especially when it comes to trusts focused on marquis New York City office space.

His argument runs like this:

Throughout the business cycle, REIT investors have harbored reservations that Big Apple office space didn’t have the same wind at its back as that of asset classes in red-hot West Coast markets. That set the market up for a lackluster year in 2018, and an especially dismal finish in December, he said.

“The fear [in New York] over the years has been that there’s been some rent growth, but nothing outstanding. And costs to acquire tenants have been increasing,” Catherwood said. “Investors whose dollars are agnostic have clearly preferred the West Coast.”

Some of New York City’s biggest office tenants—especially in the financial sector—entered the financial crisis with leases in place for wildly optimistic employment levels, Catherwood noted. But we may have reached the turning point, he thinks. As the last of the 10- to 12-year leases signed before that period have finally reached their expiration, supply and demand in the city have come to a far more stable equilibrium. And with employment growth consistently strong in the city, the economy’s strength may finally begin to correlate with firmer rent growth—with office REITs reaping the benefits. That, Catherwood said, could well be enough to put East Coast office REITs on investors’ buy lists—especially with share prices trading down from recent highs.

“That little bit of positive momentum is what we think can introduce New York City to a whole host of public market investors,” the analyst said. In a recent BTIG report, he and co-authors described 2019 as a potential “Goldilocks moment” for office REITs, with modest growth that they said could strike investors as “just right.”

If so, the after-effects of the December sell-off, he said, would only sweeten the deal. Investors will realize, “by the way, [some of these stocks] are 15 percent cheaper than they were on Dec. 1,” Catherwood said.

Anthony Malkin, the chairman and CEO of New York City’s office-centric Empire State Realty Trust, avowed that any investors moved to peruse his firm’s balance sheet would like what they find. ESRT, which controls the Empire State Building and more than half a dozen other weighty Midtown office towers, has more than $600 million in cash on its books and access to a $1.1 billion untapped line of credit—both of which, he said, would go a long way toward priming the REIT to seize on property discounts during any flavor of downturn.“

Whatever cycle hits us, we’re going to be at a very good competitive position. We clearly have a lot in the way of tenant interest in our properties,” Malkin said. He pointed out that a diverse group including Uber, Signature Bank, and software company Diligent had signed recent leases in ESRT-owned digs.

One thing ESRT hasn’t done to boost its share price is to buy back its stock—a tactic that, for example, SL Green Realty Corp. has emphasized. That trust—an ESRT competitor in the New York office market that bills itself as the city’s biggest office landlord—has spent nearly $2 billion on buying its own shares under its current buyback scheme, with an authorization to spend at least half a billion more. It’s a tactic that could emphasize the firm’s self-confidence—or indicate that it’s out of ideas for more rewarding ways to spend its money. (SL Green declined to make executives available for an interview, and representatives for Simon, AvalonBay, Columbia and Toll Brothers didn’t respond to inquiries by press time.)

Malkin distinguished ESRT’s outlook from SL Green’s approach, declaring that his company prefers to hold onto more ammunition to execute acquisitions as chances arise.

“We have not been purchasing our shares with cash,” Malkin said. “We’re actually holding onto our cash to take advantage of our opportunities.”

(Nor was SL Green’s buyback program a difference-maker for its share price in December: the trust’s stock was off nearly 20 percent on the month. ESRT’s, by contrast, fell to a low point 12 percent below its Dec. 1 price. At press time, both companies have so far enjoyed strong January recoveries.)

Michael LaBelle, the CFO of another major urban office REIT, Boston Properties (BXP), said buybacks are a strategy that his firm, too, has intentionally eschewed.

“It’s not that we don’t believe our shares are attractive, but we just have a significant pipeline of development that we’re interested in,” LaBelle said. “A balance sheet is a limited resource.” Instead of spending cash on BXP’s own equity, “we’re using our capacity to develop highly accretive real estate,” he said.

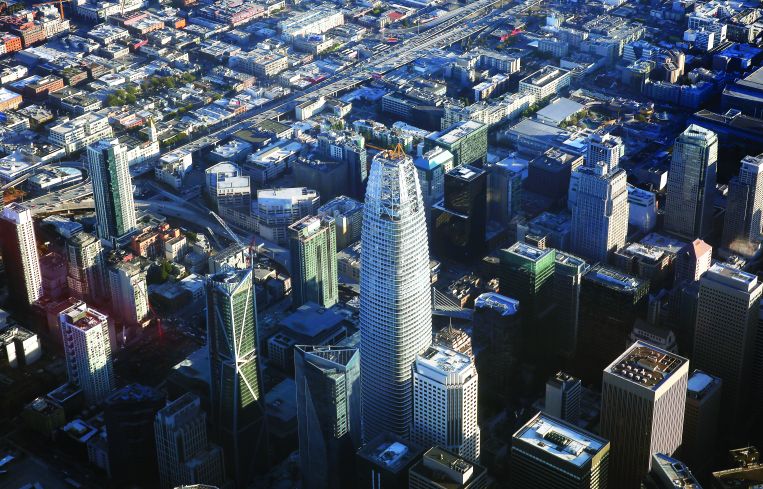

Some of the most notable examples of Boston Properties’ “highly accretive real estate” lie in precisely the West Coast markets that Catherwood said REIT investors have long favored. In San Francisco, BXP controls the Salesforce Tower, a downtown skyscraper which became the city’s tallest building when it topped out last year. And in Southern California, the REIT spent $627.5 million to buy the 1.2-million-square-foot Santa Monica Office Park last summer. Tenants there include Snap—the company behind the Snapchat app—as well as Activision Blizzard, a big video-game maker.

The Golden State emphasis hasn’t been an accident.

“I think you’ve seen us direct our investments to the West Coast, recognizing the strong economy in media and the tech sector in those markets,” LaBelle said. “It’s become a bigger portion of what we are—although that’s not necessarily at the expense of things on the East Coast.”

The firm has doubled down on its portfolio of buildings in Boston, he noted. New York, conversely, has been less of a priority.

In the five boroughs, “there’s strong demand, but there’s been some supply [growth] too,” LaBelle said. Going forward, on the other hand, he endorsed Catherwood’s thesis that the tide could be turning. “We operate for the long term, and we believe [New York City] will have higher rental growth over the long term,” LaBelle noted. “These [big] cities generally have some limitations of supply.”

If a plateau in asset price appreciation indeed implies office buying opportunities in New York City for REITs and other investors, accounting strength could separate the winners from the losers, according to Mizuho analyst Haendel St. Juste.

“You’re looking for companies that are best positioned late cycle, with their balance sheets in order,” St. Juste said. “[We like companies] who don’t have to worry about diluted dispositions or deleveraging, and who have opportunistic firepower; liquidity to make investments should opportunities shake loose.”

On the other hand, although he agreed with Catherwood’s observation that office demand in New York had diminished over the past decade, St. Juste assigned a more permanent cause: long-term shifts in the ways companies use space.

“You have less square footage per employee, and less need for some things like libraries in law firms,” St. Juste said. “And more employees are working for home.”

Trends like that don’t have him writing off New York City office REITs categorically—but they also don’t bolster his confidence for a sector-wide resurgence.

“You have to play market to market, company to company and balance sheet to balance sheet,” he said.

![Spanish-language social distancing safety sticker on a concrete footpath stating 'Espere aquí' [Wait here]](https://commercialobserver.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2026/02/footprints-RF-GettyImages-1291244648-WEB.jpg?quality=80&w=355&h=285&crop=1)