How CNY’s Dennis Prude Escaped Poverty and Rose to the Top of the Construction World

By Rebecca Baird-Remba January 29, 2019 10:54 am

reprints

CNY Group executive Dennis Prude has a life story that sounds like it was ripped from the pages of a Charles Dickens novel.

He was abandoned by his mother at age 5 and spent his childhood bouncing around homes in the foster care system in Brooklyn, from Bedford-Stuyvesant to Brownsville, and later to Jamaica in Queens. By his 10th birthday, he was shining shoes at the corner of Jamaica Avenue and 153rd Street, in front of Queens Family Court. After graduating high school in 1968 with a scholarship to play football at Pittsburg State University in Kansas, he discovered that his pregnant wife couldn’t live with him on campus. So the 18-year-old dropped out of college and began searching for a clerical job.

Prude landed an entry-level position at what was then one of the city’s largest construction companies, Morse Diesel, as a “timekeeper.” At 6 a.m. daily, he’d arrive at a job site, ask for each foreman who he had working for him, and keep attendance records for the construction supervisor. When he was six months into the job, his first construction “super,” the late Bob Rick, fired a few assistant supervisors and decided to promote Prude. That’s how his 50-year-long career in the rough-and-tumble construction industry began.

“[Rick] was a tough son of a gun and all the foremen on the job hated him,” said Prude, 68. “So I was sort of like a buffer. He’s teaching me, but he’s also using me. And he had a lot of problems with some of his assistant supers.”

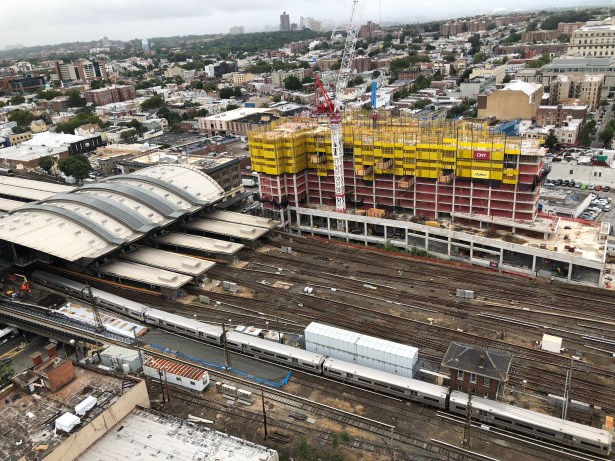

A decade ago, Prude cut a deal with brothers Ken and Steve Colao to join the executive team at CNY as a principal and director of field operations. Since then, he’s worked on the construction of the 70-story, two-hotel skyscraper at 1717 Broadway in Midtown and the 39-story mixed-use tower at 20 Times Square. Today, he’s overseeing a slew of developments, including the conversion of the upper half of the Woolworth Building to condominiums, the renovation and expansion of Tammany Hall in Union Square and William Macklowe’s 23-story residential tower at 110 University Place in Greenwich Village. He’s also wrapping up work on BRP Companies’ Crossing at Jamaica Station, a 730,000-square-foot, mixed-use development with 669 rentals. It happens to be located at the corner of Archer Avenue and Sutphin Boulevard—the same corner where he used to shine shoes in Downtown Jamaica more than half a century ago.

That same tough super convinced Morse Diesel to pay for Prude to go to college at night, and after eight years, he earned his associate degree in construction technology from New York Community College. During his evenings and weekends, he spent 18 years playing semi-pro football, serving as a linebacker on teams like the Brooklyn Kings, St. Alban’s Chargers and the Long Island Tomahawks. He even tried out for the Jets as a free agent in 1970 but eventually gave up on his National Football League dreams, because the team wasn’t offering free agents health insurance at the time, he said.

“I wound up making it, but at the time, Charlie Winter, who was the general manager, said, ‘Hey kid, 10,000 kids come down here trying to make it, but we can’t guarantee you medical for a year.’ Well, I had a baby and I wasn’t taking any chances.”

Before his 21st birthday, he took over his first construction project, a nearly-complete office building designed by Emery Roth & Sons at 127 John Street in the Financial District. The developer was the late Melvyn Kaufman of the Kaufman Organization. “A very tough owner,” Prude said. “I wasn’t used to it at the time. And in that era, there was always yelling and screaming. Nobody ever talked in a low voice in those days. I think they paid supers back then based on how loud they could yell. A lot of people went around yelling but they didn’t know what they were doing.”

The lobby was designed to resemble “a long tunnel of corrugated steel, banded along its interior with hoops of bluish neon” with two large toy soldiers standing guard at its entrance, according to a 2012 New York Times obituary of Kaufman. Rockrose later purchased the 32-story building between Pearl and Water Streets and converted it to rental apartments in 1997, scrapping the neon tunnel in the process.

The married father of five daughters, three grandchildren and four great-grandchildren said he developed a reputation that was “tough but fair.” He learned to work with the subcontractors on his projects, rather than berate them.

“The first time I met Dennis, I was scared as shit of the guy,” said Vinny Aspromonte, the head of Aspro Plumbing, who has worked for Prude on many projects over the past 27 years. He recalled that when he was first acquainted with Prude in 1993, he asked Prude why he was wearing a black cowboy hat-shaped hard hat. Prude replied, “Someone’s gotta be the bad guy around here.”

“But over the years of knowing Dennis, I’ve learned a lot from him,” Aspromonte explained. “He can be firm and forceful but he’s a man of compromise. He’s the type of guy who knows not just how to pull a team together but pull them across the finish line.”

Prude’s first big job was the renovation of Avery Fisher Hall in 1976. They spent months working around the clock to gut the building and upgrade the interiors before a New York Philharmonic performance in September of that year.

In 1979, two of his bosses, Peter Lehrer and Gene McGovern, left Morse Diesel to found their own firm, Lehrer McGovern. They poached Kaufman, one of Morse’s biggest clients, and Prude, because they knew he could work under the difficult and visionary office developer. Prude was tapped to help construct a 40-story office building at 767 Third Avenue between East 47th and East 48th Streets. While he was working on that job, he met Ken Colao, who was then a project manager at Lehrer McGovern and later recruited Prude to work for him at CNY Group.

After six years with Lehrer McGovern, Prude did a stint at Sordoni Construction in New Jersey, where he oversaw the construction of Point Liberté, a luxury residential community in Jersey City, N.J., and work on a Bell Labs facility for AT&T in Whippany, N.J. The phone company was getting ready to introduce the first transatlantic fiber-optic cable, but “the fish were eating the cable,” Prude explained. “So, they had the experimental pool that simulated ocean waves.” The building also had razor wire in the heating ducts, he said, supposedly because AT&T was concerned that “spies” would send rodents with cameras strapped to their backs into the heating and cooling system.

He spent the late 1980s and 1990s overseeing major construction projects at York Hunter and became the president of the Building Contractors Association, which negotiates collective bargaining agreements with construction unions. In the mid-1990s, Prude helped hammer out the city’s first project labor agreement in an effort to reduce the cost of construction for paper mill on Staten Island. The operator, Visy, had threatened to build its plant in New Jersey if the labor agreement wasn’t successfully negotiated. Then Prude worked at Bovis, now LendLease, from 2002 to 2009, on developments like the new Bronx Courthouse and Citi Field.

Louis Coletti has known Prude for three decades and worked with him extensively in Coletti’s role as the president of the Building Trades Employers’ Association, another contractor group. “He’s one of the unsung leaders in the industry,” Coletti said. “He doesn’t do it to get recognition for himself, he does it so he can do his job better or so the industry can improve.” Coletti added that Prude was “very straight forward. He always seems to have the facts when he has a position; he’s not going to BS you. He’s a man of integrity.”