What the Janus Decision Means for New York’s Private Sector Unions

By Rebecca Baird-Remba July 31, 2018 12:00 pm

reprints

In June, the U.S. Supreme Court delivered a major blow to the labor movement with a ruling that mandated public sector employees can no longer be forced to pay dues to unions if they decline to join the union and disagree with its political activities or positions.

The case, Janus v. American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME), revolved around the concept of public employees paying “agency fees”—often equivalent to three quarters of the normal union fee—to the union, even if they opt not to join it. The agency fees cover the benefits that public workers receive from the union’s core activities, including collective bargaining, contract negotiations and arbitration. The conservative-leaning court ruled 5 to 4 that forcing public employees to pay such fees was a violation of the First Amendment. The decision, authored by Justice Samuel Alito, directly affects employees employed by the government, including police officers , firefighters, teachers, sanitation workers and other kinds of municipal employees.

A 1977 Supreme Court case, Abood v. Detroit, laid down the rule that public workers could be forced to pay agency fees, but that agency fees couldn’t be used to fund political activities. (When workers sign up to pay union dues, they choose whether they want to pay a separate fee for the union’s political activities, which include lobbying, campaign contributions and canvassing for political candidates.) Janus overturned Abood on the grounds that all public sector union activity—including bargaining for an increased pension fund from a state government—could qualify as political activity, and it was therefore a violation of the First Amendment to force public sector employees to pay union dues. Now unions that represent public school teachers and government workers worry that a growing number of public employees will become “free riders” who take advantage of union benefits without paying dues.

Even private sector unions are worried about how the decision will affect the labor movement’s overall revenue stream and its ability to raise cash for big political pushes, like the fight to raise New York State’s minimum hourly wage to $15.

And these private sector unions play a huge role in the New York City real estate world. Service Employees International Union (SEIU) represents 80,000 window cleaners, security officers, janitors, doormen and superintendents in residential properties, office buildings, schools, stadiums and theaters in the five boroughs and on Long Island, N.Y. Similarly, the Building and Construction Trades Council of Greater New York represents 100,000 union construction workers in New York City and the surrounding counties. Union labor builds many of the city’s largest residential and commercial developments and handles major public construction projects at airports, hospitals and in the subways.

“There’s going to be a lot less money for political campaigns and to push union-friendly political legislation,” predicts James McGovern, a labor lawyer at Genova Burns. “It weakens Democrats that benefit from union contributions. These unions not only contribute money but they contribute to the ground game in politics; they’re out there doing canvassing for political candidates.”

The SEIU cut its budget by 30 percent this year in anticipation of Janus and anti-union policies from the Trump administration, according to a report from Bloomberg. Although half of the union’s 2 million members are private sector employees, the other half are government employees, such as janitors and security officers in public schools and utility workers in places like Pennsylvania and New Jersey.

“These threats require us to make tough decisions that allow us to resist these attacks and to fight forward despite dramatically reduced resources,” SEIU President Mary Kay Henry wrote in a 2016 internal memo to employees, adding that the union needed to conserve its resources to focus on political fights in 2018 and 2020.

The Janus ruling is just the latest attack in a long line of political shots at unions, which now only represent 10 percent of the American workforce, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). Twenty-eight states have passed “right-to-work laws,” which prohibit agency fees and union membership as a condition of getting or keeping a job, with formerly union-heavy states like West Virginia, Wisconsin and Michigan enacting right to work legislation since 2012. These laws have dramatically decreased union membership over the past few decades, as workers no longer have to join unions to enjoy their benefits, and have slowly suppressed unions’ political clout and spending power as they’ve collected dues from fewer employees.

In 2017, there were 117 million private sector workers in America and 21 million public sector ones, BLS numbers show. However, 7.2 million, or 34 percent, of public employees belonged to a union, while 7.6 million, or 6.5 percent, of private sector employees did. New York State has the most highly unionized workforce in the country: just over 2 million people, or 24 percent, of the state’s 8.5 million salaried workers, were in unions last year.

Labor lawyers and union leaders also worry that the ruling will embolden conservative labor groups like the National Right to Work Coalition, which funded the plaintiff in the Janus case. Those right-leaning activists may begin to push harder for right-to-work laws in the 22 states that do not yet have them, experts say.

“It’s [too] early to see what the next steps are but it’s pretty clear to me that they’re going to push more for right-to-work laws,” McGovern said. “It’s all about chipping away at the power of the unions.”

He also wondered if right-to-work groups would start urging union members to file deauthorization petitions with the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), which remove the security clause in a contract that requires employees either belong to a union or pay union dues as a condition of their employment.

Hector Figueroa, who is the president of 32BJ SEIU, which represents property service workers throughout the northeast and as far south as Florida, said he was worried about the Trump administration’s labor policy moves.

“What I’m more concerned about is the potential direction that the National Labor Relations Board can take under Trump,” he said. “The board is being populated with people who are, in our view, not friends of labor and are more likely to make decisions that are not friendly to workers.” He added that anti-union policies could push the nationwide union membership rate even lower than its current 10 percent, which would render organized labor “fundamentally irrelevant.”

The next legal challenge connected to Janus may involve employees choosing to pull out of paying their union dues after they’ve committed to them, according to labor lawyers.

“The next battle will be under what circumstances can you revoke your constitutional waiver to pay dues,” said Richard Hawkins, an employment attorney at Cozen O’Connor. Public sector employees may start to challenge how quickly they can stop paying their fees if they object to a new union political position, he said.

Still, private sector unions like the building trades and SEIU likely won’t have to worry. Major legal challenges to private sector union fees are incredibly unlikely, Hawkins said, because private companies aren’t subject to the same rules as the government.

New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo already passed legislation in April that anticipated the impact of Janus. The law requires public employers to notify the union and provide contact info for a new employee within 30 days of the worker being hired and allows union representatives to meet with the worker during orientation so that he understands why he should pay union dues. An amendment to the state budget also permits the union to refuse to represent free-riders in grievance proceedings, and the worker who opts out retains the right to bring in an outside attorney.

However, major New York City labor organizations like 32BJ, Teamsters Joint Council 16, and the Building and Construction Trades Council of Greater New York have been laying the groundwork for the past two years in advance of Janus. They have pushed to organize more workers, connect with their existing members, and become more visible in the public eye. Organizers and union representatives have been visiting and calling members in an effort to get them to commit to full union dues that include funding for political activities.

“In 1999, we found that very few members knew about the political contribution,” Figueroa said. “Now we have a significant number of members—more than one in three—contributing on a regular basis. If you ask other unions, maybe they remain anonymous and you don’t see such numbers. It’s maybe 1 in 10 [members] that contributes to the political efforts of the unions. In the past year, we have actually increased the number of people who have pledged to pay their dues and be members of the union rather than just be agency payers.”

Since the majority of 32BJ’s 170,000 members are private sector workers, like building service workers, janitors, maids and airport workers, he said that he feels that “we are among the few in the labor movement who feel they can weather this storm.”

Teamsters Joint Council 16, which represents 31,000 city municipal employees, New York City Housing Authority maintenance workers and city sanitation workers as part of its 120,000-strong membership, has made similar efforts to get public workers signed up for the union.

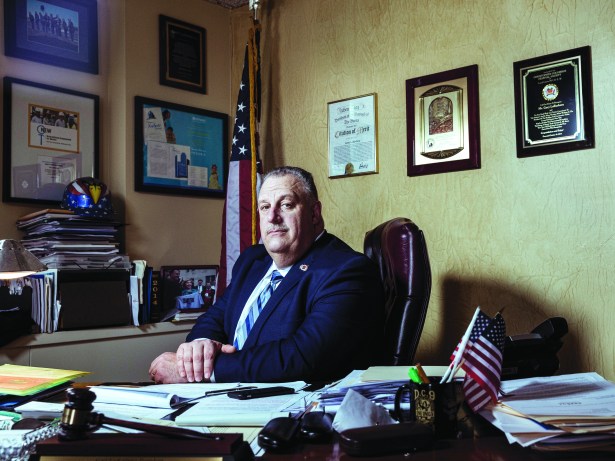

“There’s no one saying they want to be pulled out [of the union],” said the group’s president, George Miranda. “[Members] know what the union does and they know the value of being in the union, and representatives have been coming in and explaining the benefits. The representatives are constantly out there with new hires. Obviously it’s been heightened since Janus.”

And while the building trade unions are made up of mostly private sector workers, they have been raising their profile by hosting “Count Me In” rallies every few weeks at Hudson Yards, in an effort to draw attention to what they argue are anti-union tactics from Hudson Yards developer Related Companies. Building Trades President Gary LaBarbera drew a comparison between the Janus decision and Related in a recent Commercial Observer op-ed.

“When right-wing billionaires use the courts to diminish the power of public employee unions—or when right-wing real estate developers use the courts as a union-busting strategy—the negative effects are identical,” LaBarbera wrote in the July 6 piece. “It’s a constant erosion of the middle class, which helped build this city and nation.”

Ultimately, the threat created by Janus and a potentially hostile NLRB may force unions to organize even more aggressively, which may be positive for workers in the long run, according to labor leaders.

“This is a perfect time for unions to organize more workers,” Figueroa said. “Not that many unions are doing that. At this point the labor movement should be spending like none other in its lifetime organizing non-union workers…The fight against unions is real. In the long term, in the next six years or 10 years, if we don’t build a political mandate at the state local and federal level, then it’s going to be a much more bleak picture.”