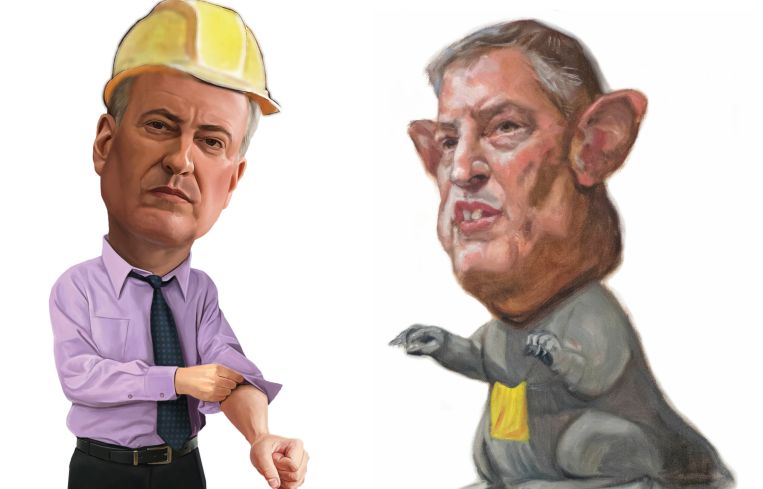

Bill de Blasio Is in a Bind When it Comes to Unions and Affordable Housing

By Terence Cullen February 21, 2017 6:00 am

reprints

There is a progressive dilemma out there with no easy solution: How does one be both pro-labor and pro-affordable housing, when one comes at the expense of the other?

This is a problem that Mayor Bill de Blasio has gracefully sidestepped during his tenure—until last week.

Since coming into office more than three years ago, de Blasio has fashioned himself a pro-union executive. He has negotiated a slew of contracts with labor groups that include those who represent the city’s uniformed police officers (even though his relationship with the New York Police Department has been less than loving) and teachers.

So it came as a surprise when the first-term Democrat last month initially expressed skepticism about proposed legislation that would require New York City construction workers to go through a mandatory apprenticeship program.

As organized labor tells it, the program is the answer to the fact that the construction industry has suffered 31 deaths in the last 24 months.

A month of back-and-forth followed in which the mayor and his staff attempted to clarify their position on the apprenticeship legislation.

So why would Mr. Progressive seemingly spend the last month siding against the unions? (Or, at least, not taking a strong stand for what would normally be an important base of support.)

De Blasio, who is up for reelection in November, was in something of a political quandary. His landslide victory more than three years ago came largely from the city’s labor unions as well as his “Tale of Two Cities” message that harped on the city’s need for affordable housing. Since taking office, he has pledged to create and save 200,000 units across the five boroughs by the mid-2020s. The only problem is that a great deal of those below-market units—especially when it comes to low-income and senior housing—is done by nonunion companies because the labor is cheaper.

“What it comes down to: The mayor has stated, unequivocally, that he is a pro-union individual. He’s never shied away from that,” said Brian Sampson, the head of the Empire State chapter of Associated Builders and Contractors, which represents nonunion companies. “But I think what it comes down to in this instance is, as you look at affordable housing, the unions have priced themselves out of being able to do that work.”

Pro- and anti-apprenticeship sides held dueling rallies outside of City Hall as elected officials reviewed the bills, along with several other proposed laws whose sponsors hope will solve the workplace pandemic. The mayor’s office first questioned the practicality of an apprenticeship program. A few weeks later, his buildings chief told the City Council implementing such a rigid program was unfeasible. Nonunion groups and the development community have maintained it would be a job killer.

It wasn’t until last Thursday, when the mayor met with the Building and Construction Trades Council of Greater New York, the union representing a bulk of the construction industry, that the mayor executed yet another pivot, clarifying his position. The two sides reached an accord in which they’d work together on developing a safety training program similar to the one union laborers go through, but not necessarily an apprenticeship program. A spokeswoman for de Blasio said this was a major step forward.

“The mayor has made clear we must protect every worker on job sites,” the spokeswoman said in a statement the following day. “We share the Building Trades and City Council goal of requiring a strong construction worker safety program, and we look forward to continuing to negotiate the details with all stakeholders.”

While de Blasio might have dodged a bullet in this particular case, the larger question of union-versus-affordable housing isn’t going to go away.

“He touts himself as a very pro-union mayor, but he’s also a competent mayor and understands that he does need nonunion labor,” said a source close to the talks. “Everyone wants to have their cake and eat it too. But when you have to run the whole five boroughs there are many cakes, and you can’t eat any of them.”

To be clear, it isn’t exclusively middle-class housing that’s typically created through programs like the 421a tax abatement. A significant amount of low-income housing in the city is done with nonunion labor, according to industry experts. This is because the rents are typically calculated at a fraction of the median income of the area, meaning the returns for a developer are not great. It often takes years for a property to become profitable. Factor in wages paid out to union workers, and it becomes impossible.

“For an affordable property, the margins are razor thin,” said one industry veteran who spoke on the condition of anonymity. “When you’re paying way too much for labor, it’s very tough to make the numbers work.”

Construction wages, factoring both union and nonunion, in 2015 (the most recent year available) were an average of $76,300 per year, according to a June 2016 report by the New York Building Congress. Salaries grew slowly from 2011, when workers made an average of $71,200 annually. The Building Congress said the molasses-pace increases could partially be attributed to a rise in residential construction (about a third of all the building activity in the city), which has increasingly gone nonunion.

A Crain’s New York Business column written in the wake of the Building Congress report determined that union carpenters’ salary was somewhere around $200,000 per year when calculating hourly wages plus benefits.

Putting a prevailing wage on construction projects receiving subsidies has been floated before. The real estate industry and organized labor were forced to negotiate a benchmark salary in 2015 and 2016 in order to save the 421a tax abatement. Those talks broke down, and the property tax break, considered the lynchpin of creating middle-class housing, has been expired for the last 13 months.

In February 2016, the New York City Independent Budget Office (IBO), a city-funded fiscal watchdog, determined that tying a wage increase to construction projects that receive city financing by way of housing bonds would be impossible. A potential prevailing wage would increase housing costs by $4.2 billion, or $80,000 per unit. (A wage bill is also included in the safety package but has been met with extreme skepticism.)

IBO’s report found that the majority of affordable projects between 2011 and 2015 were done without a prevailing wage, which is often determined by union agreements. In 2015, workers who didn’t receive an augmented salary built 4,123 affordable units, while those receiving a prevailing salary built 977, according to the IBO.

De Blasio’s housing pledge, released in 2014, aims to add 200,000 affordable units over a 10-year period, impacting some 500,000 New Yorkers. Alicia Glen, the deputy mayor for economic development, in October 2016 addressed criticism that the mayor’s office had been too slow in creating or saving below-market homes. “We are on budget and ahead of schedule,” she said at an Oct. 25, 2016 Building Congress event. “Yes, we have 144,000 to go, but it’s not like we haven’t been doing anything.”

And the numbers show that the de Blasio administration has indeed had considerable success so far. City Hall announced in January that last year it subsidized 21,963 apartments—financing the construction of 6,844 new units and the preservation of another 15,119 existing homes. The mayor’s office noted that the 2016 numbers were the best in a single year in a quarter of a century. In total, the city has financed roughly 62,000 new or existing homes over the last three years.

The mayor last week during his State of the City address said he planned to expand his housing plan given its success in 2016. It would be carried over to the least fortunate of New Yorkers, meaning the rents would be some of the lowest possible. His updated plan adds 10,000 apartments for households making less than $40,000 per year, 5,000 units for senior citizens and another 500 residences dedicated to veterans.

Those in the real estate industry acknowledge that those units and the low rent attached to them will no doubt have to be constructed with nonunion labor.

“Particularly in an environment where you don’t have any kind of tax abatement program,” the longtime industry expert said, referring to the continued expiration of 421a, “it’s very, very difficult to make the numbers work with union labor—even if you got the land for free.”

That is why many believe the apprenticeship mandate created a political headache for hizzoner. Sampson, who represents the nonunion companies, or merit shop, testified against the legislation during a marathon City Council hearing on Jan. 31 concerning the overall safety package on the grounds that it would give unions a full share of the market. His argument, which others have made to legislators, is that it would be difficult for existing workers to show documentation of their workplace training; others would have to leave their jobs and enter into a program, which their employers likely couldn’t afford to support. The result would be a massive loss of jobs, they have argued.

He told Commercial Observer last week that implementing the apprenticeship program would mean fewer opportunities for minority- and woman-owned businesses to secure construction work. That’s because they wouldn’t be able to cover the costs of sending their workers through the apprentice program, which requires classroom and on-site training. Unions, he added, wouldn’t be able to supplement the needs of the market.

“There are some other areas where, depending on the size of the project and where it’s located, maybe it could be considered,” Sampson said of union labor potentially building affordable housing. “But at the end of the day, it just makes each one of those units more expensive and takes a sector of New York City population and excludes them from that opportunity.”

De Blasio first said in mid-January that he opposed the legislation because it seemed impractical to implement. After some backlash, he clarified his statement days later during his weekly WNYC appearance, saying that while he was in favor of union labor, and increased memberships, the apprenticeship program wouldn’t address the safety problem in the short term.

“I think we have to be honest about the huge amount of construction work happening right this minute in New York City that is nonunion,” he said. “And that is a whole history that can be discussed as well—how did it get that way—but it is true right now…I’ve always believed that [union sites are safer], but the notion that we can flip a switch and make everything union overnight is not real. I want to get there, but we have to be clear about the safety problem in the here and now.”

The source close to the negotiations put it in blunter terms. “Anyone you talk to realizes that the mayor needs nonunion labor, and he cannot get any part of his affordable housing plan without them,” the source said. “The mayor knows he needs them to achieve his goals. He obviously has to be very careful not to anger the merit shops.”

The source added, “It’s well known in the industry that [that was] his reason for opposing the apprenticeship” proposal.

The City Hall spokeswoman did not comment when asked if the mayor’s initial opposition was rooted in its potential impact on affordable housing.

In his Jan. 31 testimony to the City Council, New York City Department of Buildings Commissioner Rick Chandler said he opposed the apprenticeship legislation because the program did not directly address safety. He added that it would impact workers without a high school diploma or an equivalent—something required to be approved for an apprenticeship program.

“The department recognizes the need to improve safety training for workers on construction sites, and as such supports a number of initiatives to do so,” Chandler said. “However, we do not support requiring apprenticeship programs for all workers. While apprenticeship programs have safety components, they are primarily focused on teaching a trade.”

Chandler also opposed another bill that would’ve required a prevailing wage on projects receiving subsidies. He said it didn’t directly have to do with safety and would drive up the costs of building affordable housing.

The Real Estate Board of New York, the lobbying arm of the real estate industry, and the New York State Association for Affordable Housing, a predominantly nonunion group of affordable housing developers, have toed similar lines on the legislation. While all sides agree that safety has to be a priority, they said the apprenticeship program—and the ripple effects on nonunions—would be an affordable housing killer.

“Requiring apprenticeship programs on projects receiving city financial assistance will also negatively impact construction,” REBNY said in its testimony to the City Council. “The added wage costs will increase overall costs, which could impede the progress made thus far toward affordable housing production.”

Gary LaBarbera, the president of the Building Trades Council, has maintained that the apprenticeship legislation is not an attempt by union labor to grab a larger share of the construction sector and damage nonunion builders. Instead, the union leader has said a structured training system is the only way for jobsites to be safer. His argument has been that all but three of the construction deaths in the last two years were at nonunion sites.

At the City Council hearing last month, LaBarbera indicated he would be open to an adjustment to the apprenticeship laws. The priority, he said, was to have nonunion workers receive safety training that was up to the same standards that their union counterparts had to meet.

In a statement to CO following his meeting with de Blasio, LaBarbera maintained that figuring out how to address the issue of safety was paramount.

“Implementing a strong construction worker safety program is the first step towards ending the epidemic of fatalities on construction jobsites,” he said. “Safety is our top priority, not only for unionized construction workers, but for all workers in the construction industry. The legislation before the City Council offers an effective safety training model with standards that have been proven to be the gold standard.”