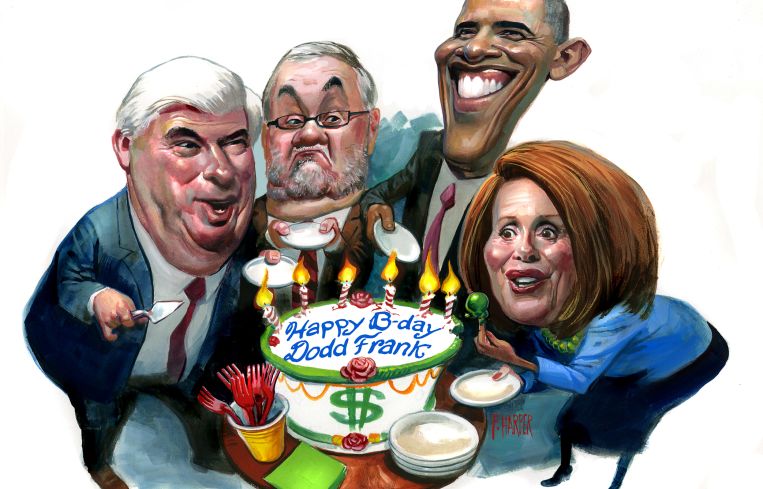

Dodd-Frank: Six Years of Success or Failure?

By Cathy Cunningham July 13, 2016 9:00 am

reprints

The Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act was signed into federal law by President Barack Obama on July 21, 2010. With that stroke of the pen came the most significant changes to financial regulation since the Great Depression, in the form of legislation that impacted almost every corner of the United States’ financial services industry.

Many measures mandated by Dodd-Frank have yet to be implemented, but the cumulative effect of the pending regulatory initiatives in concert with Basel III requirements will soon be felt by the commercial real estate industry.

Two of the most burdensome parts of the Dodd-Frank bill for CRE are risk retention of securitization and the Volcker Rule—which limits banks’ proprietary trading activities—but more simply put, the bill has significantly increased the cost of doing business.

Basel III (the third iteration of the Basel Accords, the framework for international banking put in place by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision) set regulatory capital rules that went into effect in January 2015 and intended to strengthen bank capital requirements by increasing liquidity and decreasing leverage. The regulation also introduced rules around High-Volatility Commercial Real Estate, or HVCRE, which requires all loans that meet its definition to be assigned a risk weighting of 150 percent for capital purposes.

Between Basel III and Dodd-Frank, the industry has its hands full in trying to keep up.

As the sixth-year anniversary of Dodd-Frank approaches, Commercial Observer spoke with industry participants to gain their perspectives on Dodd-Frank’s successes and failures to date, as well as one half of the legislation’s namesakes, former U.S. Rep. Barney Frank, D-Mass., who gave us his take on why the U.S. financial system is in much better shape than it was eight years ago. Just don’t ask him which event triggered the legislation in the first place.

“Is there one event in your life that explains anything?” Frank countered. “[Reporters] are always asking me that, but it’s like asking which of your six children is your favorite or what’s the best meal you ever ate. No human being has any answer. The first issue was Bear Stearns. And that is when [Ben] Bernanke and [Henry] Paulson started telling us that we had to find an alternative way to resolve these situations. We were starting to work on it, and then along came Lehman Brothers and AIG [American International Group]. The one-two punch of Lehman and AIG was the thing that triggered the panic for sure.”

The panic, a mild way of putting it, had been brewing in the credit markets for 18 months. The subprime crisis was in full swing by the summer of 2007 with banks and hedge funds left holding worthless assets and residential originators New Century and American Home filing for bankruptcy protection. Bear Stearns’ demise began with the liquidation of two hedge funds that invested in collateralized debt obligations and ended with $30 billion of its assets being guaranteed by the Federal Reserve. By 2008, the U.S. was in a recession. September of that year saw the failure of Lehman Brothers, the conservatorship of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, a $85 billion government bailout of AIG and the closure of Washington Mutual Bank.

Convulsions in the U.S. financial system sent markets across the globe into a tailspin. The Dodd-Frank legislation, drawn up by former Sen. Christopher Dodd, D-Conn., and Frank, sought to ensure that a financial crisis of that magnitude never happened again, and met the economy’s downward spiral with what Obama termed a “sweeping overhaul of the financial regulatory system.” Their bill aimed to increase transparency, cease financial markets’ excessive risk-taking and use of opaque investment vehicles, protect American homeowners and consumers, and build a safer financial system that would provide a robust foundation to boost economic growth.

Today, six years in, the legislation draws either glowing praise or scathing criticism, depending on who you ask. CO thought it only right to begin with Frank himself, who took us back to its inception.

“I think [Dodd-Frank] has been very successful,” Frank said. “The biggest problem initially was that the Republicans took over the House and substantially underfunded the two agencies that [had been given] a lot of new power to deal with derivatives. One of the biggest changes that Paul [Volcker] made was to regulate financial derivatives, which had previously been unregulated. And of course there were a lot of problems with AIG, for example, and others. They were regulated by the [Securities and Exchange Commission] and the U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission—they should have been consolidated but they reflect such deep divisions in American society between agriculture and finance that there was no political way to get it through.

“The arguments that [the bill] was going to be a job-killer have been refuted by the fact that the U.S. economy has performed better than any other economy in the world. I think the [Consumer Financial Protection Bureau] is working well; you have seen a move on the part of banks away from some of the financial activity that benefited the banks more than the economy, more towards lending and wealth management, and there has been a clear move to de-emphasize trading. That to me is a healthy thing.”

But not every part of the legislation has played out as intended. “There was one unintended consequence that I am for changing,” he said. “I think that some of the smaller banks that aren’t covered by some of the rules, in particular the Volcker Rule, have spent too much money proving that they are not out-of-compliance with the rules that were never aimed at them in the first place. I supported, a couple of years ago, Federal Reserve Gov. Dan Tarullo’s proposal, that will exempt banks under $10 billion [in total assets] from the Volcker rule. I agree with Tarullo that the $50 billion [asset threshold for stress tests] was too low and it should go to $150 billion and be indexed.”

The requirements of the bill have not yet been fully implemented, however, and so calling it a success or a failure may be a little premature, noted Oliver Ireland, a partner at law firm Morrison Foerster. “As we sit here in 2016 approaching the sixth anniversary, we do not know what the banking market will look like in the United States when we are done. We know it will have a lot of new rules, but we don’t know how liquid it will be. We don’t know how it will function because there are a lot of changes. But, these changes aren’t coordinated or integrated, and they weren’t a planned whole. The interaction between them is still to be learned.”

Ireland believes that overall the economy and financial system are in much better shape than they were in 2008, but there was room for improvement along the way. “Could Dodd-Frank have done a better job in improving the financial system and improving the economy? I think the answer is yes. Would we be better off if we had done nothing? Probably not. I think to the extent that ‘too big to fail’ is perceived as an issue that we needed to address going forward, a lot of progress has been made in addressing that issue. I guess I look at this [legislation] and I see a mixed bag.”

Too Big to Fail

Indeed, one key goal of Dodd-Frank was to prevent another mammoth taxpayer bailout of a “too big to fail” institution. “The [larger banks] are no longer seen as immune to failure,” Frank said. “We see that with GE [Capital] divesting [its financial arm] and the way that they are becoming less complex in lending. Some people say, ‘Well, if a bank fails, it will still be bailed out,’ and I’m astonished that people say that. It would be illegal for any federal official, specifically the federal director of the Treasury, to step in and pay the debts of a failing institution without abolishing it. It would be a crime. And people say, ‘Well, if a major financial institution was failing there would be political pressure to save it.’ Absolutely the opposite. The country is furious, there would be political pressure to shoot them.”

Frank also pointed to the perceived success of the annual stress tests that were implemented. He described the bill’s three-level approach to failure in firstly making sure that banks are less likely to fail a stress test, secondly disallowing banks to reach the level of indebtedness that others reached in the past—for example, when AIG failed it had approximately $150 billion in credit default swaps—and finally, if the first and second approach fail and unlike in 2008, the options today aren’t simply “all or nothing” in terms of paying the failing institution’s debts.

Risk Retention

One of the most anxiety-inducing aspects of Dodd-Frank for the CRE industry and issuers of CMBS in particular is the risk retention requirement, colloquially referred to as keeping “skin in the game.” The rule requires that CMBS securitizers retain a 5 percent economic interest in the credit risk of the assets they securitize as incentive to ensure quality assets and underwriting.

Beyond affecting CMBS issuance and pricing for borrowers, issuers will have to take down higher costs because of lengthier underwriting times. Additionally, retaining a percentage of deals on their books will mean less free capital for banks to leverage. Compliance with the rules for CMBS shops is required by Dec. 24. Merry Christmas?

“People say, ‘You won’t get mortgages made if you have to retain the risk,’” Frank said. “Well, apparently there were no mortgages made in America before 1975, because before 1975 there was no securitization. Everybody retained the risk.”

Industry group CRE Finance Council is one organization closely watching the risk retention implementation unfold. “There is some concern as to how far policy-makers have pushed the button on controls versus liquidity,” explained Michael Flood, the deputy executive director at CREFC. “Will regulations drive CMBS issuance out of highly regulated banks and into the nonbanks and still be a viable product? I think the jury is still out.”

In CREFC’s “severe impact” scenario, cumulative regulation costs could place as much as $15.4 billion of CMBS capital at risk this year, prior to the point of implementation in December.

“When it comes to trying to cure the ills of the past, which is the intention of the bill and a laudable goal, I think that the next two years will determine soon how successful it is,” Flood said. “Issuers and investors alike are trying to figure out whether there are structures that will align interests and be profitable. With risk retention specifically, I think next year we will know whether the regulators have struck a balance between the alignment of interest and issuer profitability or whether adjustments still need to be made to the regulations.”

David Wright, a managing director in Deloitte & Touche, who also worked on the Federal Reserve Board during the crisis and was part of the team behind the stress test framework, said the success of risk retention has yet to be determined. “There was a lot of debate on whether forcing people to have skin in the game actually results in better balance,” he said. “It’s certainly going to make folks more careful than they otherwise would have been, but it also has eliminated some players who have no interest in being financial intermediaries for the balance sheet.”

CRE is pretty resilient, however, Flood said. “If CMBS falls in issuance, then whole loans, and to some extent agencies, will likely pick up the slack. I imagine that life insurance lending, bank direct lending, private capital and mezzanine lenders would pick up the demand. But maybe the better question is will CMBS remain a viable part of the commercial real estate debt lending portfolio? The entire industry believes in CMBS and sees it as a necessary portion of CRE lending, especially for small and medium sized metropolitan areas. I think we will find out in 2017, when the rubber hits the road, as that is when a lot of the capital rules outside of Dodd-Frank will be implemented along with risk retention.”

One CMBS bondholder spoke strongly on the subject. “I think the market is screwed,” he said. “Retaining the risk is a very expensive cost for the issuing banks and could remove all profitability from the trade. The interesting part here is that everyone is trying to figure out a way around it. If everyone adhered to the rules—just say $1 billion of bonds were issued, retaining 5 percent would kill the CMBS industry.”

The bondholder said that not only will the selection process for securitized loans change, but there is an increased likelihood of execution risk. “This affects the issuer and the originator, if they differ,” he said. “An originator may not be able to securitize certain loans that have too low of a coupon. If a buyer is looking for more yield, that means a higher coupon and origination at a higher rate.”

Credit rating agencies are also more accountable than ever for their CMBS rating actions as a direct result of Dodd-Frank. The regulations called for increased analysis of securities and full disclosure and transparency of their due diligence methods. Frank blames securitization itself for taking the responsibility off the lender and the “absolute wackiness of the rating agencies, who were just making stuff up so that people would buy these mortgage packages without having any idea of what was in them, and being reassured by the rating agencies who had no idea what they were doing. They were making money by giving inflated ratings to people selling the securities.”

Volcker Rule

Another of Dodd-Frank’s focuses was on ensuring that financial institutions were restricted from engaging in any risky activities that may threaten the stability of the financial system. The Volcker Rule limits banks’ proprietary trading activities—trading with its own money, for its own profit, rather than investors’ money—as well as investments in private equity funds and hedge funds. Banks have until 2019 to fully implement some of the requirements of the Volcker Rule, but there are fears that the limitation could affect the liquidity of commercial real estate markets.

The rule has also invoked something of a power shift away from the regulated investment banks and trading firms, whose hands are now tied in making risky bets, to largely unregulated asset management and private equity firms.

“My personal vote for the biggest waste of effort coming out of this [legislation] is the Volcker rule,” Ireland said. “It takes a huge effort to implement it, and what are we getting in terms of public policy benefit? That’s not clear to me. Paul Volcker never liked proprietary trading. It was bad unless you were doing it in the government securities market, in which case it’s good? I don’t get that.”

One of the biggest exceptions to the Volcker Rule is the exception that allows market-making trading based on reasonably expected near-term demand (RENTD). Trading desks must file estimated allocations for the future demand of a deal in order to prove that the firm’s positions are tied to client demand, and they aren’t engaged in proprietary trading. Regulators have the ability to penalize any disparities in the filings.

“It’s forcing the market to be very transparent—you can’t say a deal is oversubscribed if it isn’t true, which is good, but at the same time, it’s stifling activity,” the bondholder said.

Unsurprisingly, some of Dodd-Frank’s harshest criticism comes from the Republican Party, although the protests haven’t been overly loud, Frank said. “There are two major things that the Democrats did in Obama’s first years—healthcare and financial reform. Republicans have repeatedly voted to repeal healthcare, but they have never voted to repeal financial reform. They’ve worked at the edges, because they don’t want it to be popular. Even Jeb [Hensarling, R-Texas]: Three-and-a-half years into his chairmanship [of the House Committee on Financial Services] he comes out with an outline of a bill that nobody believes can even be considered. So in fact [the Republican Party has] no alternative. If Hillary [Clinton] is elected, as I believe she will be, it will then be clear that this law is here to stay, and at that point we can begin to make some of changes to it.”

Changes he foresees include increasing the $50 billion Volcker exemption for smaller banks and appointing the “right regulators.”

But for now, Hensarling is pushing ahead with “The Financial CHOICE Act” as an alternative to Dodd-Frank. The bill, backed by conservatives, aims to curb regulations implemented by Dodd-Frank to “create opportunity and choice for investors, consumers, and entrepreneurs nationwide,” according to a Financial Services Committee release.

Congressman Robert Pittenger, R-N.C., backs the bill and said that the financial markets should have been allowed to self-correct back in 2008.

“We need to have a market-driven financial system,” he said. “Markets correct themselves—that’s the dynamic. There are bad actors, but we have laws to come after bad actors. What [Dodd-Frank has] done is create so much restriction in the market that there is no movement in the economy. That’s why your economic growth and job creation is so dismally low.”

Key among Pittenger’s critique of the legislation is access to capital. “There is lack of capital and credit in the market, and that small entrepreneur who has been the lifeblood of our economy, can’t get capital. [The American economy] didn’t grow because we had a great government, it grew because of opportunity and freedom. Today that capital is not to be found, because the banks are too restricted,” especially small- and medium-sized banks, he said.

The Price of Lending and Borrowing

It’s true, the costs of implementing Dodd-Frank have been substantial.

Assuming the regulators do not change the rules too much, the median 10-year impact on the real economy from all of the pending regulation headed our way is estimated to be $209 billion, according to a CREFC’s report, The Impact of Regulation on Commercial Real Estate Finance. The analysis also suggests that smaller borrowers, lenders and markets bear a disproportionate percentage of the costs. Looking at the impact from the bottom up, the addition of a single data point into the reporting framework of a small- to medium-sized firm can exceed $1 million.

Additionally, CREFC estimates that future regulation will add additional costs of 10 basis points, at a minimum, for high-quality loan and debt product platforms at lightly regulated institutions to 100 bps for lower-quality loans made in smaller metropolitan areas and debt at more highly regulated institutions.

Preparing for new regulations has brought post-crisis stresses for lenders and borrowers alike, but some of it may be necessary, Wright said. “It’s safe to say that there has never been a more challenging period of regulatory work in terms of meeting regulators expectations, the billions of dollars being spent to upgrade all of the systems and just changing the way firms are governed,” said Wright. “The regulatory agenda has become the agenda for the majority of the largest firms. So it’s been very challenging from the data side, the infrastructure side and really in recalibrating and improving the risk management systems. Some say it’s overkill, and others say it’s deferred maintenance from before the crisis.”

Congressman Pittenger used Regions Bank as an example of the regulatory cost burden. “Today [Regions has] more compliance officers than loan officers, directly because of Dodd-Frank. So, the compliance costs have gone up significantly for all banks, and the smaller banks can’t support that, and they can’t afford it. So they either merge or go out of business. They certainly don’t start up,” he said.

As we enter into a new presidential election cycle, the market should “go through a period of examining the financial regulatory system,” and any tweaks should be done on a case-by-case basis, Ireland said.

In the meantime, industry participants are still working their way through the layers of overlapping regulation.

“Why we are really scratching our heads is [because] we don’t see the regulators giving any value to Dodd-Frank controls as they finalize Basel rules for capital and liquidity,” said Flood. “Why do Dodd-Frank controls have value in terms of the alignment of interest between issuers and investors, but they have no value when it comes to capital and liquidity rules? In fact, capital and liquidity requirements are increasing in the face of increased Dodd-Frank controls.”

Flood pointed to the European Union, whose regulators have publicly recognized that they have overcorrected the securitization market and are currently revisiting their own regulations for securitization in order to be able to fund small and medium-sized enterprises—the core target for CMBS lending. E.U. regulators are contemplating implementation of a “high-quality securitization” concept that would allow for a lowering of capital and liquidity requirements if certain structural controls are implemented.

“While I can’t say CREFC would endorse the HQS program itself here in the U.S., we would certainly endorse the concept that adding controls—such as those mandated by Dodd-Frank—should have some value when considering capital and liquidity requirements,” Flood said.

“No regulatory body that I am aware of is looking at how these rules align to understand the entirety of the effect on CMBS issuance and liquidity,” Flood said. “Anyone who walks into their boss’ office and says, ‘We have to implement these 10 things,’ but can’t answer how that [implementation] will affect business will probably be asked to leave. Yet we struggle to get this type of analysis from the regulators.”

As time passes and the final requirements are implemented, the law has its share of advocates and critics, but Frank takes comfort in the increased supervision of the market going forward, and believes that the regulation has immunized the U.S. economy to systemic threats, including the United Kingdom’s recent vote to leave the E.U. and the subsequent aftershocks.

“Unlike in the past, the Financial Supervisory Oversight Council has the ability to look into things so nothing is totally unregulated,” he said. Nonbanks, like peer-to-peer lenders and hedge funds, are next on their list, Frank said.

It’s safe to say that some parts of the regulation won’t be missed by Frank, however. “On the day I left office in January 2015, I modified an old song in my head and sang it to myself, but the lyric was, ‘Ain’t going to study derivatives no more.’ That’s true of capital levels as well. I would have sung it to you in the old days, but with the advent of YouTube, you have to be much more discreet,” he said.