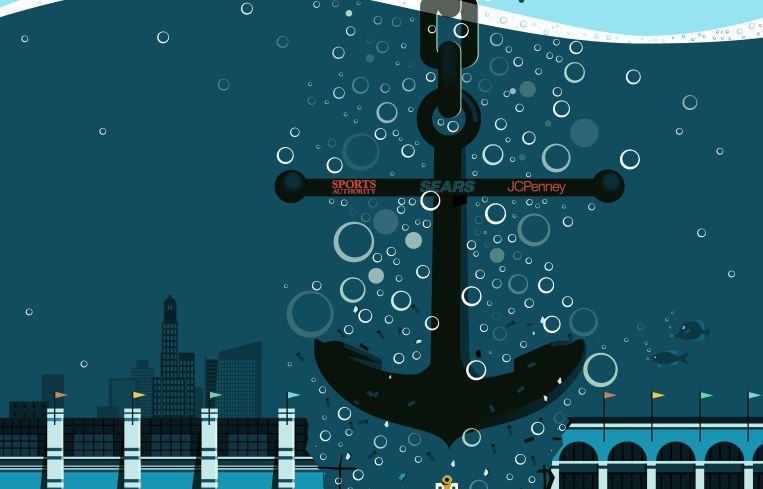

Anchors Away: How the Loss of an Anchor Tenant Is Felt Down the Retail Chain

By Cathy Cunningham June 8, 2016 9:00 am

reprints

Retail has been a troubled stepchild of the real estate industry of late—shunned by some, kicked out of commercial mortgage-backed securities for anticipated poor performance by others, handed over to special servicers with an order to shape up or ship out, and the cause of continuous hand-wringing by anxious industry participants, from borrowers to banks.

With approximately $57 billion of retail loans set to mature by the end of 2017 and slim pickings when it comes to refinancing opportunities, watchful industry eyes are narrowing their gaze on the heart of a retail property’s cash flow—the anchor tenant.

Trusted household names such as Sears, Kmart, J.C. Penney, Sports Authority, Macy’s and Aeropostale have announced bankruptcies or store closures. The aforementioned stores are all core anchor tenants in numerous retail properties across the U.S., so what happens to satellite tenants when the heavy weight that grounds them abandons ship?

“The loss of an anchor tenant not only hurts a property’s cash flow; it also will negatively impact traffic at the center. A large dark store is an eyesore,” said Greg Reimers, the regional manager of real-estate banking at J.P. Morgan Chase. “Satellite tenants are likely to suffer until the anchor is replaced.”

Anchor tenants are placed in a retail property with a certain level of clout. This clout allows the anchor to pay a reduced rent in return for the expected foot traffic it will draw. Accordingly, a satellite tenant moved into that center because of the influence that the anchor will have on its own foot traffic and revenues. Like the cool kid in school, if people visit the anchor, chances are they’ll stop by to say hello to you too, her less popular sidekick, purely for proximity reasons.

So much importance is placed on the anchor tenant’s role in the retail center that other tenants’ leases often include a specific clause that some consider a necessary evil—the co-tenancy provision.

Co-tenancy provisions are commonplace in retail leases and allow tenants certain concessions from retail owners if anchor tenants leave their space. An anchor is a big draw for consumer spending, and one of the main reasons that a smaller tenant locates to a specific retail site. Co-tenancy provisions help protect tenants should the anchor leave with the idea of compensating for loss of traffic and subsequently reduced sales.

“A few scenarios can occur when that co-tenancy clause kicks in,” explained Edward Dittmer, a vice president at Morningstar Credit Ratings. “One is that a tenant might be able to terminate its lease if that space hasn’t been filled within some pre-specified period, or the tenants can actually reduce their rents to some prespecified number of percentage of sales. If [an] anchor leaves and those clauses are invoked, you can lose money through lease terminations and rent reductions that have already been contractually agreed to.”

A co-tenancy provision, however, is not simply black and white language that states because X store closes, Y tenant can pay percentage rents, said Yaromir Steiner, the founder and chief executive officer of Steiner + Associates. For example, sometimes the co-tenancy language states that, if two out of three anchors remain open, then nothing in the contract changes, and a store can go dark without consequence. In other cases, the language may state that, if the anchor store goes dark, there is a 180-day-long or even year-long grace period to find a replacement anchor, and if a replacement is found, there is no consequence. Other language may state that the sales of satellite tenants will be reviewed, and those tenants will have to show that there is in fact material impact on their sales caused by the departure of the anchor store before claiming any damages or a reduction in rent.

“This is the reality clause,” Steiner said. “A tenant can say the anchor is now gone and that will hurt their business, but what if that tenant’s business is not hurting at all? And what if, as a result of the anchor’s departure you are actually selling more sporting shoes [for example]? You could be adding insult to injury to punish a small developer who already lost its anchor.”

Steiner went on to say that the retail industry is relatively cooperative industry. “Generally, if a developer or landlord is getting hurt unnecessarily because the lease is in the tenant’s favor an agreement can be reached. Nobody wants to see the mall fail. There is always room for compromise and negotiations.”

The extent of the damage to a property’s cash flows when an anchor leaves, one retail owner-operator explained, can be partly dependent on the type of rent that its retail tenants are paying. That income could be base rent or base rent plus percentage rent. It also may include the tenant’s share of common area maintenance and real estate taxes related to the operation of the real estate, which are considered “reimbursable” expenses in that they are reimbursed to the owner. Although the owner is relying on the income from the base rent or additional percentage rent, they similarly rely on the reimbursable expenses being paid.

Operating expenses are subtracted from gross income, and part of that gross income is this reimbursable expense from each one of these tenants. If a co-tenancy provision is triggered, sometimes the tenant no longer has to pay the reimbursable expense, and that cost goes straight to the owner’s bottom line, who then has to then pick up the tenant’s share of that operating expense plus the anchor’s share, which could be considerable given the size of its space.

“Co-tenancy provisions provide very little upside to the lender,” Reimers said. “At best, it is a necessary concession for an owner to give to a prime tenant they want in their center. At worst, it gives a tenant the right to restructure or terminate their lease if another tenant leaves or goes dark. If a number of tenants have co-tenancy clauses, then a bad situation can become worse very quickly.”

Joseph Cafiero, the president at Brooklyn-based CREMAC Asset Management echoed this sentiment. “If a retail tenant vacates anchor or big-box space upon expiration of its lease term, the real estate owner needs to be concerned about co-tenancy and restricted use provisions that exist in leases of the remaining tenants,” he said. “These provision can have an adverse economic impact if co-tenancy provisions are triggered and create an increased challenge releasing the vacated space as a result of the restrictive-use provisions, which can limit the pool of potential replacement tenants.”

An additional distinction to make is the difference between an anchor tenant leaving at the expiration of its lease term and vacated space that is a result of the tenant “going dark.” “If the tenant goes dark, you don’t necessarily have the ability to re-lease it right away considering the space is still in the tenant’s control until the expiration of the lease term,” Cafiero said. “An operator’s worst nightmare is having a five-year term left on a lease and the retail tenant not giving up that space for five years, electing to keep paying rent on the vacant space. Now you have to deal with the negative stigma resulting from the vacant space, a dark big-box space that is very noticeable, and have significant consequences over a prolonged period of time.”

Given that co-tenancy provisions are expected within leases, an anchor’s stability needs to be measured. “Solid credit quality and strong sales performance for an anchor tenant is important and the longer the lease term the better,” Reimers noted.

One way to determine the longevity of that anchor is to underwrite its sales per square foot, the key being to determine whether an anchor’s sales at that particular retail center is above or below the sales per square foot thresholds that the operator sets. For example, if an anchor tenant’s sales per square foot are $225 dollars and the anchor publicly reports sales averages of $120 per square foot, the anchor is faring well and will likely be kept open and leases renewed. On the flip side, if the average sales are $225 dollars per square foot and your anchor is only reaching $120, there is cause for concern.

Whether having multiple anchor tenants increases or decreases risk to a retail property’s cash-flow is debatable. If an operator is looking to mitigate risk by putting a couple of big box tenants in a center, it may also be increasing risk to some extent. Several large spaces are harder to refill and whichever tenant is in between the anchors will pay reduced rent until they are filled. Additionally, big-box tenants require certain footprints and have certain requirements in terms of the space they seek, and not every center can accommodate multiple big-box tenants.

If an anchor’s space can’t be filled by a similar tenant, it’s time for the retail owner to get creative. The migration in certain markets is toward lifestyle-type developments that can absorb the large vacant space.

Steiner gave Simon Properties’ replacement of Saks and Nordstrom at Orlando’s Florida Mall with a large food court and the Crayola Experience as an example of effective repurposing. “It was the right thing to do as this mall needed to be remerchandised and responsive to its customer base,” he said.

But, certain covenants within co-tenancy provisions mean that this transition may not always be so easy. Restrictive covenants often prohibit the space being leased to tenants that differ significantly from the original anchor—for example, in terms of credit rating or type of operation. These restrictive provisions, coupled with noncompete provisions that disallow competing retailers from occupying the space, can place operators firmly between a rock and a hard place.

Despite the issues often caused by co-tenancy provisions, they are expected as commonplace in a retail lease. Even with the recent wave of retail bankruptcies, these provisions should not be reworked, said Cafiero. “The effects that these provisions may have on today’s retail properties are somewhat expected in a market that is overleveraged and overbuilt, a maturing real-estate cycle,” he said. “Recent research reflects a retail market that is about 40 percent overbuilt. We have 40 percent more leasable square footage in retail than we need. So you have 40 percent of retail that needs to be refit somehow.”

Steiner opined that in some cases, the departure of an anchor tenant can actually be a good thing. “Sometimes the departure of a department store is actually good news because it opens up a remodeling or remerchandising opportunity that may be more beneficial to the mall,” he said.

From a lending perspective, “The retail sector can still be attractive to lenders,” said Reimers, “but some of the current challenges facing anchor tenants and retailers need to be carefully considered.”

New York, as always, is a completely different animal. The former location of Toys “R” Us in Times Square has been vacant for some time, yet the space doesn’t have a negative perception because the public knows that it will eventually be filled by Gap and Old Navy, said Adelaide Polsinelli, a senior managing director at Eastern Consolidated. “We’ve been here before, where a big tenant leaves and everyone says, ‘Oh, my God, the sky is falling in,’ and, ‘What do we do now that we don’t have as many big retail tenants in need of big retail spaces?’ This is two-fold. Sometimes it is best not to have all of your eggs in one basket and cut up the space to make three or four tenants. And, you know what? It’s survival of the fittest.”